Intersectional Learning Dis/Abled Poetry as Teacher Education: A Phenomenological Study of Learning Dis/Ability Diagnosis of Two Scholars

By Lisa Boskovich[1], Ph.D.

Chapman University

David I. Hernández-Saca, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

University of Northern Iowa

[1] Both authors are co-lead authors given that we worked collaboratively and democratically in our division of labor on the research and writing. We are listed in alphabetical order by last name.

Abstract

The coming together of two scholars from distinctive philosophical frames provided dual perspectives utilizing constructivism and critical theory at the intersection of dis/Ability and its construct in teacher education. Each scholar holds a Disability Studies in Education (DSE) perspective in the analysis and in their view of dis/Ability. Each author used poetry which provided a pathway for each author in this phenomenological study in their reflection of their learning dis/Ability diagnosis at their intersections of identities and power. Through the use of a combined spiritual and emotional paradigm their growth unfolded. We asked: How can the sharing of phenomenological LD experiences at their intersections of power and identities with preservice teachers impact their praxis of teaching? However, within this article, we utilized it as a type of sharing about the larger study, that we can come back to and reference for its theory and methodology used in the larger study. We only reported on the analysis of our phenomenological reflections about our LD poems in order to set the stage for future publications. This research fills a gap within the DSE literature, through the first-person understanding of two DSE scholars who have or were labeled with an LD for theory, research, practice, policy and praxis at the boundaries of traditional special education and DSE teaching and training.

Keywords: Learning Disabilities, Intersectionality, Disability Studies in Education, Teacher Education, Spiritual and Emotional Paradigm, Phenomenology

The process(es) of individuals with Learning Disabilities (LD) creating and forming their identities at their intersections of power and emotionality are powerful healing moments. The purpose of this study was to highlight the phenomenological experiences of two Dis/Ability[1] Studies in Education (DSE) scholars with or were labeled LD as they identify with their intersectional identities in educational settings. We were interested in both informing students with LD voice literature and developing teacher voice for critical emotion praxis—the coupling of critical thinking, reflexivity, and feeling before acting—within educational systems (Artiles & Kozleski, 2007; Freire, 1972; Zembylas, 2015). The research question guiding our study was: “How can the sharing of phenomenological LD experiences at their intersections of power and identities with preservice teachers impact their praxis of teaching?” However, within this article, we utilize it as a type of sharing about the larger study, that we can come back to and reference for its theory and methodology used in the larger study. We only report on the analysis of our phenomenological reflections about our LD poems in order to set the stage for future publications.

This research fills a gap within the Dis/Ability Studies in Education (DSE) literature, through the first-person understanding of two DSE scholars who have or were labeled with an LD (referred to as “Boskovich and Hernández-Saca”). This work provides a much-needed space to explore LD through a combination of feelings, thoughts, and experiences from a spiritual and emotional paradigm. Those are as a result of being labeled with an LD within programs for special and general teacher education preparation. Additionally, this study provided opportunities for the Boskovich and Hernández-Saca to further reflect on their life experiences within the special education system, and, in particular, the assessment system for LD (e.g., within the context of LD diagnosis). In turn, this study provided opportunities for the co-lead authors to develop their teacher educator voices.

First, we present our understanding of DSE in the context of teacher education for general and special educators. Second, we outline our spiritual and emotional paradigm and phenomenological methodology. Third, we outline our data collection and data analysis and present our phenomenological narrative themes. Fourth, and last, we present our discussion, conclusions, and implications sections.

Our Interdisciplinary Dis/Ability Studies in the Context of Teacher Education

Our conceptual framework includes three theoretical frameworks and methodologies; (a) Dis/Ability studies in education (DSE); (b) heuristic phenomenology; and (c) a spiritual and emotional paradigm. Each of these provided a rich and robust lens to undo intersectional disablism (Iqtadar et al., 2020) and counter-narrate our authentic selves about the LD diagnosis context and being labeled with LD. We briefly situate each of these and how they each contribute to the significance of our topic and expand on them later.

Our work bridges the current gap in the field of Dis/Ability Studies in Education (DSE), the connecting of spirit restores the damages each author experienced in life. This work reaches past the current research in the multilayered experiences of dis/Ability and praxis. In dis/Ability research, there is a paucity in the literature that connects the experiences of dis/Ability with emotional and spiritual paradigms. Our work aims to build a bridge and connect these two vital and important areas. We operationalize this spiritual and emotional paradigm through heuristic phenomenology. The word heuristic comes from the Greek word heuriskein, meaning “to discover or to find” (Moustakas, 1990, p. 9). The two authors’ use of heuristic phenomenology offers researchers opportunities to explore their own experiences with an LD diagnosis. This specific methodology provided a safe space for each researcher to explore their own life narratives and reconcile a path of healing (Sultan, 2019). The writing of poetry offered an avenue for deep reflection, central to the growth and reconciliation of each researcher. This process is an internal journey as heuristic research has the researcher reflect and dialogue upon their thoughts and experiences (Sultan, 2019).

Dis/Ability Studies in Education

We grounded our study upon a Dis/Ability Studies in Education (DSE) paradigm (Ware, 2017) that centers the voices of historically marginalized students and people with dis/Abilities at their intersections of identity (Annamma, et al., 2013; Charlton, 1998). Additionally, DSE provided us with an alternative view of LD, within the canon of special education (Freedman, 2016; Gallagher, 2010; Reindal, 2008).

Given special education’s positivist philosophical stance, LD is located inside the individual’s “mind and body.” DSE provides a re-conceptualizing of dis/ability for the researchers. Dis/ability, therefore, becomes an innate accepted part of self, and removes the socially, discursively, materially, and linguistically intersectional psycho-emotional impacts associated within the medical model (Gallagher, 2014; Galvin, 2003; Iqtadar et al., 2020; Reindal, 2008; Thomas, 1999). This model de-centers the body and the mind as the location where the “the hunt of disability” (Baker, 2002) and its “fixing” occurs, through cognitive, emotional, and social deficits. Our collective work of identity reclaiming was constructed from a spiritual and constructivist framework (Crotty, 1998; Kegan, 1982, Lambert et al., 1995). The special education paradigm and LD assessment remain based on a medical-psychological and information-processing model of disability that ignores and erases (a) culture; (b) identity; (c) the construction of self; (d) issues of privilege; and (e) power (e.g., intelligence labels and classification of special education) (Artiles et al., 2011; Arzubiaga et al., 2008; Crotty, 1998; ).

Research as a Spiritual and Emotional Paradigm

The embracing of a spiritual and emotional paradigm is central to the construction of this study. The recognition of one’s dis/Ability is inherently connected to the deepest soul of self. As Frankl stated, “A spiritual research paradigm turns to our very motivations and nets all our endeavors in a deeper quest for meaning, one that is different for each and every one of us” (1959) (p. 98). The recognition of dis/Ability is a process of personal acknowledgment when combined with one’s spiritual and emotional paradigm, there is inherent power in healing as false beliefs are cast aside. As a result, the soul and mind of self-healing as dis/Ability becomes a place of acceptance and empowerment. This healing is a choice as is the recognition of dis/Ability through a lens not chained to old beliefs and false perceptions. Lin et al. (2016) write of the spiritual paradigm:

A spiritual research paradigm requires an ontology that considers all reality to be multidimensional, interconnected, and interdependent. It requires an epistemology that integrates knowing from outer sources as well as inner contemplation, acknowledging our integration of soul and spirit with the body and mind. Three additional aspects are useful to a spiritual research paradigm: axiology, methodology, and teleology. An axiology concerns what is valued, good and ethical. A methodology is the appropriate approach to systematic inquiry. A fifth and less frequently mentioned aspect is teleology, an explanation of the goal or end (telos) to which new knowledge is applied, such as gaining wisdom and truth, touching the divine, increasing inner peace, exploring hidden dimensions, or improving society. (pp. ix-x).

For us, we anchor a spiritual paradigm, to interrogate the meanings of disability, and in particular Learning Disabilities (LD), in the traditional canon of special education and what has either been said or communicated, directly and indirectly, about the meaning of LD and the idea of LD. We are interested in how these meanings have impacted our spiritual and emotional growth, and how they have oppressed us. However, a spiritual and emotional paradigm allows us to resist such master narratives of LD. Those master narratives of LD are the theories and assumptions encoded into policies and practices of traditional special education. More often than not, those practices are not defined by those living with disabilities or those who are “found” to have one of the 13 categories of the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) of 2004 (Lee, 2020). For example, the more subjective categories of IDEA such as a Specific Learning Disability, a Speech and Language Impairment, Emotional Behavioral Disorder, and Intellectual Disabilities. The moral and spiritual imperative of the problem of disproportionality of more Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) youth with and without disabilities being labeled with special education also compounds the issues of the social and emotional constructions of disabilities in education (The BIPOC Project, n.d.).

Our spiritual paradigm is distinct from our emotional paradigm, but they are related. Elsewhere, Hernández-Saca, along with his colleague has articulated what counts as an emotional paradigm undergird by literature from the affective turn and critical dis/Ability studies at the intersections of identity (See Hernández-Saca & Cannon, 2016; 2019). There and here we define an emotion paradigm that counts for the psycho-emotional disablism model of disability. This model bridges the medical-psychological model with the social model of disability by accounting for the personal experiences, well-being, and agency of youth and people with impairments given the social and attitudinal barriers experienced in society and institutions. Emotions, feelings, and affects are not conceptualized within and as youth and people with impairments per se. But they are cultural, political, historical, social, spatial, interactional, or relational. Additionally, they are institutional in nature as opposed to purely biological and psychological to the individual. In other words, they are contextualized and embedded in power relationships. We are interested in the meaning-making of people with impairments about their intersectional dis/Ability experiences (Hernández-Saca et al., 2018). We define spirituality as “the connections that are both internal and external and metaphysical that all humans can and do tap into for meaning-making to and through ideational, relational and material means” (Hernández-Saca & Cannon, 2019, p. 10). In turn, our spiritual and emotional narrative analysis is centered on not only the what of our storytelling about our experiences of intersectional dis/Abilities, but also the how; and how the emotive and spiritual is encoded in our narratives or emotion discourse (Moir, 2005).

The utilization of a spiritual paradigm within qualitative research is based upon the quest to find answers to questions that drive our souls in our journey to construct meaning (Boskovich & Hernández-Saca, 2019; Crotty, 1998; Dillard & Okpalaoka, 2013). A spiritual paradigm requires the researchers to be aware of their ontology and their multidimensional, interconnected, and interdependent existence (Lin et al., 2016). This is a unique spiritual experience inside each of us that grows through our continued dialogue (Crotty, 1998). We see the roles of emotionality and spirituality as interconnected (Boskovich & Hernández-Saca, 2019); we conceptualize emotion and spirit as in a dialectical materialism relationship to feelings and affect as social, political, and relational in nature and its role in human development (Ahmed, 2004; Au, 2017; Erevelles, 2011; Rogoff, 2003; Wetherell, 2012). By emotion, we mean the biological and physiological ways in which this state has a life of its own mediated by social, discursive, and material practices as feelings and affect (Moir, 2005). By affect, we mean the energy one feels as one acts or is enacted on by emotion discourse within social practices (Moir, 2005), which both affords and constrains one’s ability to act (i.e., agency; Ahearn, 2013). Our question becomes, how will our work serve the public good? Therefore, it is through the sharing of our LD diagnosis as researchers that healing begins as we speak and teach our truth. It is through this hope that another generation can be spared the individual pain that we experienced.

Phenomenological Methodology

Our study is built upon four core transcendental phenomenological ideologies situated within a Dis/Ability Studies in Education frame based on (a) consciousness, (b) intentionality, (c) researcher context, and (d) researcher’s positionalities and relationalities (Paul et al., 2009; Phillips-Pula et al., 2011; Reiners, 2012). From a DSE framework, “Nothing About Us without US” (Charlton, 1998) is anchored by the acknowledgment of the voices of historically marginalized students and individuals at their intersections of power and identities. Our discipline is both interdisciplinary and intersectional, combining Critical Race Theory and Dis/Ability Studies (DisCrit) and constructivism (Annamma et al., 2013, Crotty, 1998). We also cull from DisCrit’s tenets, which value the voices of those with intersectional identities; combat the social construction of intersectional oppression along the lines of race, ability, and western cultural normalcy; and acknowledge both the material and psychological impacts of labeling (Annamma et al., 2013). Our philosophical, epistemological, and methodological perspectives explore and structure an individual’s conscious experience through a DSE and constructivist lens (Crotty, 1998; Paul et al., 2009). Phenomenology honors the individual experiences of the researchers throughout the research process while maintaining the voices of the participants (Moustakas, 1985, 1990; Sultan, 2018). The exploration of an individual’s dis/Ability at their intersections of power, identities and emotions, feelings, and affects is a phenomenological study of experiences.

Consciousness

Consciousness, constructed within a phenomenological construct of intentionality, is situated within the context of our experiences and formed through constructivist and dialogical means (Crotty, 1998; Moran, 2000). This self-awareness is born out of our experiences with ourselves and the world. It is constructed and developed through human interaction and transmitted within a social, emotional, and spiritual context that is pragmatically subject to ongoing change (Crotty, 1998). Therefore, consciousness is born out of connection through intentionality so that meaning is brought to life; each researcher grappled with the construction of meaning and the realization that essence is a social activity (Kegan, 1982).

Intentionality

The sharing of the researchers’ experiences with their invisible dis/Ability in early childhood, primary and secondary education, and higher education. This intentionality was grounded in their phenomenological, DSE-situated experience through reflection, meta-cognition, and emotion (Crotty, 1998, Lambert et al., 1995).

Researcher Context

The researchers brought a body of (a) personal; (b) professional; and (c) theoretical knowledge to the conception, construction, and implementation of the study.

Situation of the Researchers’ Experience

The study originated in the early stages of our critical friendship and colleagueship (Costa & Kallick, 1993; Russell & Schuck, 2004), beginning in 2017 when Hernández-Saca read Boskovich’s Master of Arts (M.A.) in Special Education thesis. This journey opened up pathways for two individuals to build their joint growth through a total of 109 memoed notes throughout Boskovich’s MA. The memos were short notes and questions each raised and then answered. The researchers asked deep questions regarding the construction of dis/Ability at the intersections of power and identities, as defined from a constructivist and DSE lens.

Positionality and Relationality

Boskovich was diagnosed with an LD in Perceptual Organization upon returning to college after dropping out. After her master’s degree program was completed, the stronghold and wasteland of victimhood were healed. This was possible through shifting the lens of self out of victimhood and the strong female mentors in her life.

To hold the view that oppression and ableism drive the foundations of my scholarship and the theoretical frame is false. I am not a critical theorist. I continue to wrestle with the discourses of Dis/Crit with my solid foundation of constructivism. Is there oppression and ableism? Yes, I acknowledge both and the continuing fight for dis/Ability equality through the intersections of my subjectivity. Boskovich’s intersectionalities formed through constructivism, within the foundations of DSE rather than critical theory or Dis/Crit.

Hernández-Saca was labeled with an auditory Learning Disability and received special education services in K-20 Education, in addition to having the following intersectional identities: bilingual in Spanish and English; gay; cis-male; mixed-ethnicities of El Salvadoran and Palestinian; U.S. immigrant; first-generation student; working-class; and fairly recent U.S. citizen.

Heuristic Inquiry and Approach

Heuristic phenomenology is a specific phenomenological discourse with the researchers having a direct experience and/or connection within the research (Douglass & Moustakas, 1985; Moustakas, 1990, 1994, 1995; Sultan, 2018). Heuristic comes from the Greek word heuriskein, meaning “to discover” (Moustakas, 1990, p. 9). The heuristic approach originated with Clark Moustakas, who focused on how meaning is revealed and derived through the researcher’s involvement in the data. A phenomenological view upholds that knowledge is acquired through the interactions between the researcher and participants (Sultan, 2018). The heuristic process of data analysis is revealed through the data combined with their understanding of self.

Boskovich’s Individual Growth

The choice to grow is personal. This decision reaches through the past as hidden passageways, first only known to self, become the lens of reconstruction of one’s life experiences. This study offered a safe and brave space for growth for each of us. This change and movement began before meeting Hernández-Saca and continued as I shared my MA with him, and throughout this study. Boskovich’s growth additionally was facilitated through the many conversations with her mentors. Those mentors included her: MA degree chairperson, Disciples of Christ Reverend, and her Grounded theory Professor. Mentoring, combined with the exploration of self through poetry, opened the doors of her healing. Writing poetry is an act of self-trust, an examination of the self. This was and continues to be a process of evolution for both researchers. Our life experiences added to the individual experiences of growth, as individuals are not static. The writing of poetry as healing began during the writing of her MA degree and continues still today.

As a constructivist researcher, the act of research becomes a living document of self’s experiences, and, if one is open, growth has the potentiality to occur. The formation of my constructivist epistemology is, as Crotty (1998) stated, “truth, or meaning, [that] comes into existence in and out of our engagement with the realities in our world. There is no meaning without a mind. Meaning is not discovered but constructed” (pp. 4-5). My life experiences added to the individual experiences of growth, as individuals are not static. This interaction with the world is formed from, “the theoretical construct of constructivism, where the focus is on the construct layers of ‘interpreted sedimentation’” [emphasis added] (Crotty, 1998, p. 59). This constructivist lens opens the doors for layers of meaning that research and the combination of writing poetry make possible (Lambert et al., 1995; Lincoln & Guba, 2013).

Hernández-Saca Human Development and Growth

As a teacher educator and educational equity researcher at a predominately white institution, I adhere to critical theories within the social sciences to investigate the emotional and spiritual impact of learning disability labeling on intersectional conceptions of self. This study is an example of this line of research, but one that employs critical emotional, affective, and spiritual autoethnographic methods; theory, and praxis as methodology; counter-emotion-narrative and theory (Hernández-Saca & Cannon, 2019) for Hernández-Saca personal and professional growth and participation. Grounded in an interdisciplinary cultural and equity-minded stance (Artiles et al., 2011), I center a cultural-historical developmental theory approach to human development (; Hedegaard, 2008; Hedegaard et. al, 2011; Hernández-Saca, 2017; Rogoff, 2003). A cultural-historical developmental approach understands the important role culture plays in human development and defines learning as change in participation within cultural traditions in human activity (Hedegaard, 2008). Culture is understood as a noun, and a verb within cultural-historical activities, such as learning to read and write or write poetry or going to school. This is complementary to a Disability Studies in Education paradigm regarding learning and teaching. It foregrounds the role of the social and cultural mediation of learning, and access to the ideational, material, and discursive tools (Nasir, 2011) within learning and teaching environments for equitable and equal participation for all.

Consequently, how I conceptualize learning is not individual or meritocratically, but grounded in sociocultural learning theory (Mahn, 1999; Vygotsky, 1978) and cultural-historical developmental theory and method. Given our different training within our doctoral programs, Boskovich’s and Hernández-Saca 2 approach and define individual, human development and growth in unique and different ways. We see this as a strength. We anchor the auto- in dual auto-ethnography to honor our individual journeys and perspectives that we each bring to our collective purpose. This purpose is the problematizing of common-sense assumptions of what Learning Disabilities are and the role that master narratives about LD have played qualitatively differently in each of our lives, but more importantly our emotional and spiritual lives.

I feel and think that I am finally ready to let go of all my trauma with the label, Learning Disability (LD), and Special Education stigma and negative energy. It has been a damaging experience for me and not one that I would wish on anyone. The labeling and classification systems that our educational culture and larger society have created needs to change. I want to be healthy to see it come to pass. Our mental health is not our own per se. How we make meaning of our past trauma is not isolated from our social relationships, the larger society, and the cultural and emotional narratives circulating about it. Current mental health systems categorize and label, and further dehumanize the self, becoming who one truly is or would like to be. This has been the case for me and my relationship to the special education label LD at my intersections of power and privilege.

Methods

To research is to begin a journey, formed out of separate and joint piles of clay the process began. For researching requires and asks much of self when the subject matter is so personal, and soul driven. This joint investigation was formed and constructed through trust and the mutual desire to share a different narrative connecting the use of emotional and spiritual paradigms. Boskovich is a constructivist and Hernández-Saca is a critical theorist. This research brought forth our respective pedagogies. This offers the opportunity for two scholars to share each other’s respective lenses in the study, while providing opportunities for individual and professional growth.

Research Steps

Our research process consisted of the following steps: (a) we discussed the importance of individual growth in each of our lives through the recognition of healing from our experiences of our Learning Disabilities (LD); (b) this discussion resulted in David reading and commenting on my MA degree; (c) a decision was made that each of us would present our LD journey’s in David’s Special Education Classes (4150) of Pre-service teachers classes over a period of two years; (d) Lisa and David each wrote poetry that described their relation to their LD’s; (e) data was gathered from each section of the SPED 4150 Pre-service teachers totaling 97 student participants, (note) this accounts for the missing semester’s data from Spring 2018 Course Section 1 of 12 students); (f) 54 students participated in an on-line questionnaire sent out prior to each class; (g) Lisa and David conducted an analysis of the data; and (h) data discoveries resulted.

Boskovich’s Use and Role of Poetry

The writing of poetry is a process and an act of research (Wakeman, 2015). Ely et al. (1997) stated, “creating poems has been an extremely successful activity for many qualitative researchers” (p. 136). Poetry expresses phenomenological experiences and assists in the understanding of pain, resolution, and in healing. It is an often-overlooked form of written expression in the process of research and analysis (Eisner, 1998, 2003). Often, poetry compresses ideas in short and declarative sentences or phrases, as illustrated in Boskovich’s poems. The use of poetry has the researcher review data in a different form, offering new ways of seeing themes and the connecting of data points (Wakeman, 2015). Through the usage of poetry, hunches and the interpretations of lived experiences are reflected as internal and external growth and revealed through the written words. Verse paints pictures that offer the researcher greater opportunities for growth as short sentences frame a continuing exploration of self.

Poetry serves as the vehicle for the unearthing of unconscious thoughts, affects, feelings, and beliefs; the mind opens. Overall, as Leggo (2008) stated, “poetry creates textual spaces that invite and create ways of knowing and becoming in the world” (p.167). Poetry defeated the internal walls I held in silence while offering a release and opportunity to reach beyond , who held false, Boskovich’s constructed assumptions of self. In her poetry, her narrative embraces short declarative statements. From her poem Labeled, “Accommodations felt like separation . . . Produced Deficit feeling. DSPS advisor watching, Through a closely guarded lens. …” and continued in the poem, I am x-1,

There never was room for me. Smart Triggers

{ 0 } an empty set

Vulnerability

Fear

Self-loathing

And a Lifetime

Of being left out and not belonging…..

Boskovich’s use of poetry opens the mind’s confines through short and declarative statements reflected through the self’s inner lens. The movement to healing is represented in the poem, Continuous Variable, emotional and spiritual healing emerges out of the blackness:

For once there is no documented evidence,

No test scores,

No scatter plots or bar graphs,

To measure me against another…

I claim my own self now.

I am my own Qualitative variable…

Not defined by anyone,

But by me….

The use of poetry offered each researcher opportunities to emerge from old pain and experience the freedom that inner critical analysis can bring when the body, mind, soul, and spirit make this choice and are united as one. We situated these feelings, emotions, and the effects are socially and culturally created so that we need to move out of ourselves to be free and liberated. This is what the power of poetry, supported by a DSE paradigm, facilitated for us and our inner revolution toward growth.

Hernández-Saca’s Use and Role of Poetry

I was never a poetry writer before I met Boskovich. Boskovich introduced me to the world of poetry writing. Boskovich introduced me for a very specific reason: to help me undo decades of psycho-emotional disablism (Thomas, 1999) at my intersections of power and identities that were socially, emotionally, politically, and culturally engendered into my unconscious mind and heart. This is the level of what I call intersectional Learning Disability: emotions and special education trauma that both white and ability supremacy (at my intersections of power and identities) did to my development of self and a healthy intersectional identity development. This trauma also involved being an immigrant, a refugee, and a dual language learner and was unspeakable. I am bilingual in Spanish and in English, and a person of color. All these aspects contributed to the unspeakable impact of intersectional disablism (Iqtadar et al., , 2020). However, the role of poetry helped me speak back to the cultural global racist and ableist hegemony that I was experiencing every day in K-16 and beyond educational contexts. Boskovich helped me become a poet by sharing her M.A. thesis with me, in which she wrote over 800 poems; from that number 83 were chosen. In reading her thesis and analysis of her poems regarding her experiences with a perceptual learning disability, I was able to learn and grow as a poet. In addition, throughout the years, Boskovich was also able to support some of my pre-service teachers, particularly one of my honors students in developing writing poetry skills. Boskovich was able to create a narrative, “On Narrative Writing and Poetry” (See Appendix F), from which I could also read and learn. In other words, poetry is both method and theory for me as I express my old LD emotions and special education trauma in the process of healing from the personal, interpersonal, structural, and political (Crenshaw, 1990) dimensions of how the hegemony of the field of learning disabilities, special education, and dominant society shaped and spirit-murdered (Erevelles & Minear, 2010; Williams, 1987) my inner self and psychological well-being, nearly separating me from my dignity and humanity.

I further note that poetry is one of many healing tools I use to resist both white and ability supremacy at my intersections of power and identities, to humanize myself given my intersectional dis/Ability oppression and dehumanization in and around educational contexts (Freire, 1972). Other healing tools include mental health counseling and psychotherapy, painting, cognitive behavioral therapy, prayer, connection to my ancestors and family, living and past, cooking, walking, and journaling. However, poetry, like each of these activities, is unique and contributes to who I am as a person emotionally and spiritually; and, more importantly, who I am becoming and growing.

Data Collection

Data were collected from undergraduate students in special education and pre-service teaching courses, totaling 109 students beginning the fall of 2017 to spring of 2019 (See Appendix A, Table 1, for a summary of all data sources statistics across semesters, sections of the course, and student participants). Technical issues during Boskovich’s presentation in the Spring of 2018 prevented the data from being recorded. As a result, the data from 12 students was not included in the data analysis. Data sources included: (a) a section of Boskovich’s Master thesis in Special Education and three LD poems (See Appendix C); (b) Hernández-Saca wrote 3 LD emotional-laden poems (See Appendix D); (c) in-person focus groups that were recorded as video and audio; (d) the pre-service teachers uploaded their responses to the pre-questionnaire (See Appendix B), either prior to the focus-group or afterward.

The above data sources were constructed and presented in the following temporal order: (a) during the fall of 2018 and spring 2019; (b) Spring of 2018, then shared 7 poems during fall 2018 and read the 3 same poems; but shared 9 poems during spring 2019. This was done since Hernández-Saca kept writing poems about his LD and special education trauma; (c) Hernández-Saca facilitated the focus groups during fall of 2017 and spring 2018; (d) Boskovich facilitated the focus groups during Hernández-Saca presentations during fall of 2018 and spring of 2019; Each presentation lasted for approximately one hour and Google forms were used to collect the pre-questionnaire surveys for each section of the course from the fall of 2017 to spring of 2019 (See Appendix B). Each focus group was recorded, and the files were professionally transcribed verbatim.

Analyzing Our Intersectional LD Experiences as Teacher Education Praxis

Data analysis for both Boskovich and Hernández-Saca occurred through careful and thoughtful heuristic processes (Sultan, 2018) and was facilitated through: (a) re-readings of the student’s comments from their posted on-line questionnaire answers; (b) significant statements taken from the focus group’s transcripts; (c) the presenters’ poems were analyzed; and (d) further themes generated from Boskovich’s phenomenological reflections, presented through narrative reflection (Moustakas, 1972, 1975, 1995; Sultan, 2019) and for Hernández-Saca’s phenomenological reflections through emotion-laden narrative analysis (Edwards, 1999; Moir 2005; Prior, 2016). However, the themes shared within this article are only those generated from Boskovich and Hernández-Saca’s phenomenological reflections and analysis of their narratives and emotion-laden narratives from their poems.

Presenters Narrative Reflection & Student Focus Group Transcripts

Presenting our poems and narrative in our study over a year offered another opportunity to share with our students, who would become teachers soon. The utilization of narrative methodology attends and frames how a story constructs, how the cultural discourses are drawn upon (Trahar, 2009; Polkinghorne, 1991; Andrews et al., 2008). Where the events of our lives are examined into meaning-making experiences viewed through the lens of the story (Andrews et al., 2008; Trahar, 2009). Time gives the writer a space of reflection, a held essence of feelings, and experiences to examine, often fostered by need or by a collective call to understand. There is inherent power in sharing, we are all worthy, and everyone no matter the disability is capable of not only learning but thriving. To be open to healing is a journey whose destination centers into the heart of self. Healing takes a path all of its own and cannot be mandated or held tightly; this only produces inner strife and moments of sheer frustration. To feel is to heal and to heal is to feel, these two intertwined, they are similar yet different like winter’s first snow upon a parched earth.

Boskovich Phenomenological Narrative Reflection of Poems

Boskovich’s analysis of her poems was filtered through a phenomenological lens, through a wanting to know the essence of her experience (Moran, 2000; Moustakas, 1990, 1994, 2019; Sultan, 2019; Vagle, 2014; Van Manen, 2014). This type of data analysis is centered upon wanting to know and is reflected in the philosophical work of Indian philosopher Krishnamurti (1956). His life and teaching centered around the construct of understanding the experiences of life is based on questioning. This questioning was based upon the living of the individual’s experience. This wanting to live the experience is directly connected to the essence of a phenomenon is the foundation of phenomenology (Moran, 2000; Moustakas, 1990, 1994; Phillips-Pula et al., 2011; Sultan, 2019; Vagle, 2014; Van Manen, 2014).

Across the data that was collected, Boskovich paid attention to her thoughts and experiences, as new paths of self-knowing were created and are reflected in each of her poems. The journey of growth is often fraught with inner struggles as old ways of being and thinking are abandoned. Reflection offers the researcher opportunities to examine the past in the context of the now while holding a space for growth.

This analysis was based upon a single data set that includes:

- open- and descriptive-coding (Saldana, 2009).

- a second layer of focused coding derived from the work of Charmaz (2014).

- Both were then filtered through a heuristic lens (Sultan, 2019).

The purpose was to develop themes and answer the following questions:

- What did the data say?

- Is the data consistent?

- What are the common themes?

This will result in Boskovich’s phenomenological themes consistent with the poems.

Hernández-Saca Phenomenological Emotion-Laden Narrative Analysis of Poems

Emotion-laden talk (Prior, 2016) and heuristic methods (Moustakas, 1972, 1975, 1995; Sultan, 2018) guided the preliminary data analysis of the following Fall 2018 sources: (a) emotion-laden talk poems; and (b) focus group’s transcriptions. By emotion-laden talk, I mean emotion discourse (Edwards, 1999; Moir, 2015; Prior, 2016). Emotion discourse is indexed within talk or texts in the form of opinions, responses, reactions, and so forth and is situated within social practices (Moir, 2005).

Across the Fall 2018 data sources, special attention in the analysis was made to the role of emotions, affects, and feelings encoded in the texts using a type of constant comparative analysis used to identify emotion-laden talk. The type of constant comparative analysis (Boeije, 2002; Glaser, 1965) Hernández-Saca adopted was comparison within a single data set that includes:

- open- and descriptive-coding (Saldana, 2009).

- summary of the core data set.

- finding consensus on interpretation of fragments.

The purpose will be to develop categories understandings and specifically to answer the following analysis questions:

- what is the core message of the data set?

- How are different data fragments related?

- Is the data set consistent?

- Are there contradictions?

- What do fragments within the same code have in common?

This will result in a summary of the data set, construction of provisional codes (code tree), conceptual profile, and extended memos (Boeije, 2002; Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995). Within and across the constant comparative analysis, in order to identify how emotions, feelings and affect played a role in my LD label and special education phenomenology, Hernández-Saca also focused on the “WHATs”—the content of the text—and the “HOWs,” —through emotion implicative WHATs (Prior 2016) (e.g., sexism, trauma, ableism, and so forth) and intensifiers (Labov, 1984) (e.g., SO sad, REALLY angry, a LITTLE anxious, and so forth)—of not only my own emotion discourses but across the entire corpus of the Spring 2018 data sources. Lastly, the above procedures were conceptualized as the Hernández-Saca’s phenomenological emotion narrative reflections in order to generate his themes (Sultan, 2018).

Transformative Self-Discoveries

Below we present our generated themes based on our analysis of our phenomenological reflections about how sharing of phenomenological LD experiences at our intersections of power and identities with preservice teachers impact their praxis of teaching. However, as we explained from the onset of this article, we focus on our analysis of our phenomenological reflections regarding our poems to help us set the stage for future publications regarding our larger study. In addition to presenting our transformative self-discoveries below in the form of themes, we summarize them within Table 3, located in Appendix G.

Boskovich’s Phenomenological Narrative Themes

The study’s themes for Boskovich’s presentation included: (a) vulnerability; (b) shame; (c) combined identity and LD Labeling; (d) deeper learning of dis/Ability and healing shame; (e) resilience; and (f) LD acceptance.

Vulnerability

Courage is presented through the presentation of transparency and vulnerability in my poems, for example, in Labeled, “Wasn’t I a whole person?… I didn’t want to be separate.” This release opens my heart and frees further bonds of fear and inner lacking and inadequacies. Some moments happen in the most unexpected of times; speaking and presenting offered just this. The truth lies in the spoken and written words when there is no sharing, truth, and freedom is stagnant, sitting below the surface, the surface of shame.

Shame

Shame is a powerful force that when combined with fear, crushes the construction of self. Shame found a resting place in my poem, I am x-1,

For smart Connotates (x)’s function I am x…

There never was room for me…

Self-loathing,

And a Lifetime,

Of being left out and not belonging. …

Shame was also spoken about during my presentation to the focus group of students. I retold my experience of taking math tests out of class as an undergraduate, “You’re taken out of the classroom with your peers. You know you’re different.” I continued with a story from grade school, “I was placed in the lower classes, separated, and segregated from those who my private school teachers viewed as smarter.” My experience of shame drew out the life force inside of the self, called I. I carried shame, and it became part of my identity.

Identity and Learning Dis/Ability Labeling

We are all more than one story, one narrative, so too is our identity. It is a complicated weaving of what each person calls truth. The truth that can only originate from within the individual, whose heart speaks what the mind cannot always claim. For identity isn’t static, it’s constructed upon layers and layers of life experiences and self-defining truths, just as our stories are. This is illustrated in the poem Labeled, “Test scores determined, An LD in Perceptual Organization.” Across the page did the nib of the pen sail, without thought or hesitation; its course set to true north. Who are we? How does the intersection of Identity and labels mark us?

Identity and labels wrap around us, like slots marked in chosen ink, not always by our hand. I shared with the student focus group my disability advisor’s words, “Your test results. Stack up against someone who would be in the normal range in math and perceptual processing. You have a learning disability in perceptual organization and some ADHD.” Perhaps, the dependency rests upon the shoulders of the label’s receiver, not the giver of possible identity? Dropping LD from my narrative of identity released my internalized constructs of shame and the labeling given by my Disability Services advisor.

Deeper Learning Dis/Ability Healing Shame

Writing hundreds of pieces, both poetry and narrative, and completing my MA degree while presenting them over nine years has healed the grip of shame around my learning dis/Ability story. The sharing of my narrative transformed the broken, filled places I carried throughout my undergraduate experiences from disability assessments and years of using my granted accommodations. Innate dis/Ability healing from labeling takes time, patience, and the belief that its possibility is not a faraway dream found in another country. Healing is a transparent process of growing. It requires asking the self: what face do I show to the world when the school world has hurt me over and over again? As presented in I am x-1, “There never was room for me. Smart Triggers / { 0 } an empty set.” It is through the looking glass of self, combined with the patient and caring mentors who helped heal the darkness of fear, shame, and non-acceptance that I had built around my identity.

During the student focus groups I shared this one powerful and life-changing statement from my teacher, Alison Williams (with her permission) “Lisa, you don’t have a learning disability. Your brain processes math differently and we are going to find out how.” Did I still have a labeled diagnosis? Yes. However, this self-granting of grace released my being from the grip of shame. Where shame once made a home now stands an empty glass whose water has been poured out upon a grave that continues filling with grace.

Resilience

The theme of resilience was demonstrated in the poem Labeled: I was so much more than a graph that represents LD test scores. My inner resilience’s construction was possible because of my mentors and a continuing desire to understand myself and my continuing experiences in the world. My openness to examine the hurt the LD diagnosis brought provided a pathway for my acceptance that my identity was not based upon a set of diagnostic tests and plotted graphs.

Acceptance

Acceptance is a journey that walks into the deepest sources of one’s soul and self. Exemplified in my poem, Continuous Variable,

My choice to explain.

Just what it means to be me.

I claim myself now.

My journey of self-acceptance is not linear; it is through transparency in writing and dialogue with others that this occurs. However, without courage, there is no possibility of transparent vulnerability. This acceptance of self-brought wholeness and, in that, the overcoming of my LD. Therefore, every individual has a choice in the definition and defining of self. The recognition of transparency acceptance understands and is aware that courage and healing is a choice; it is a leap into the void.

Emotion-Laden Narrative-Themes

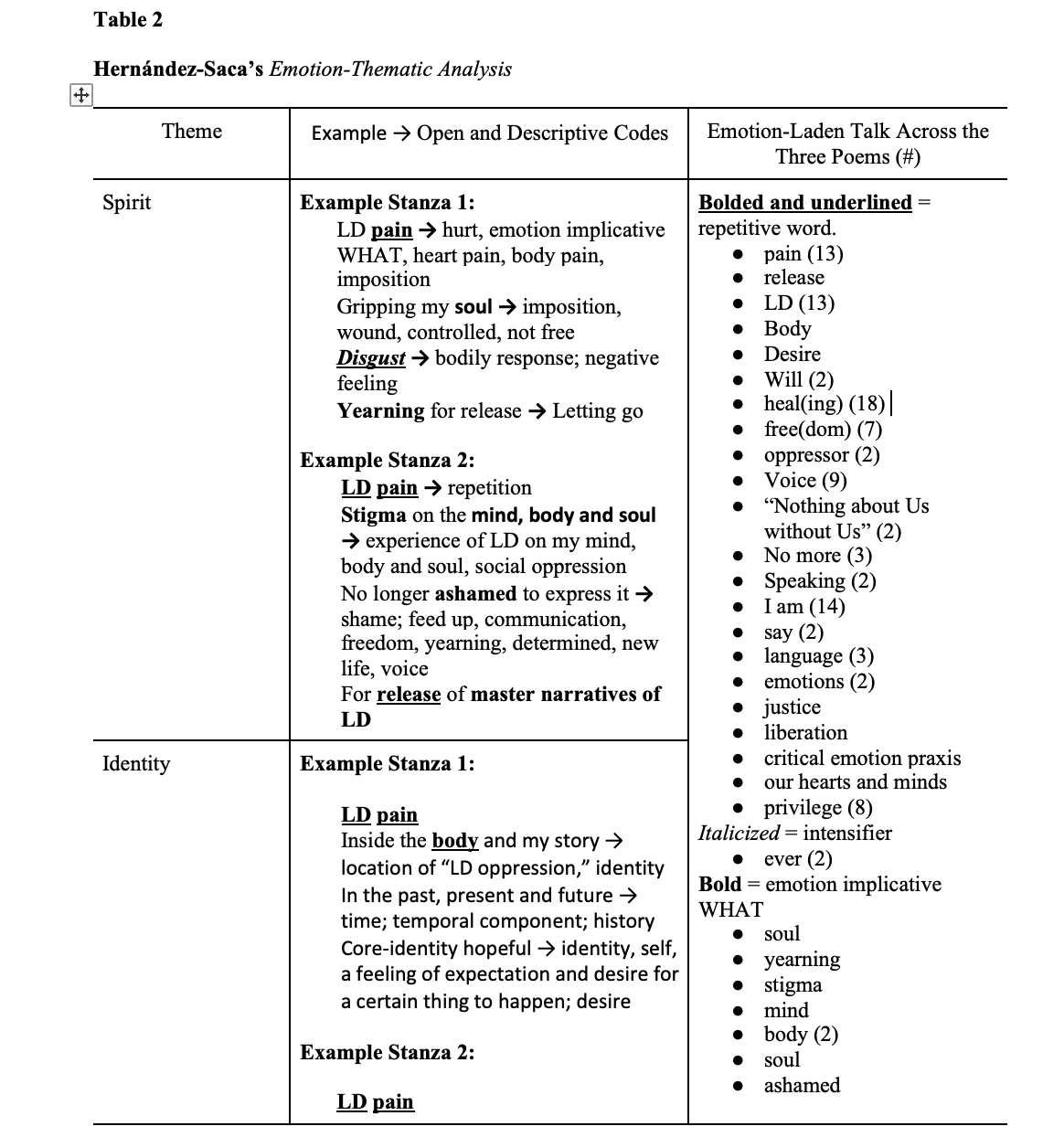

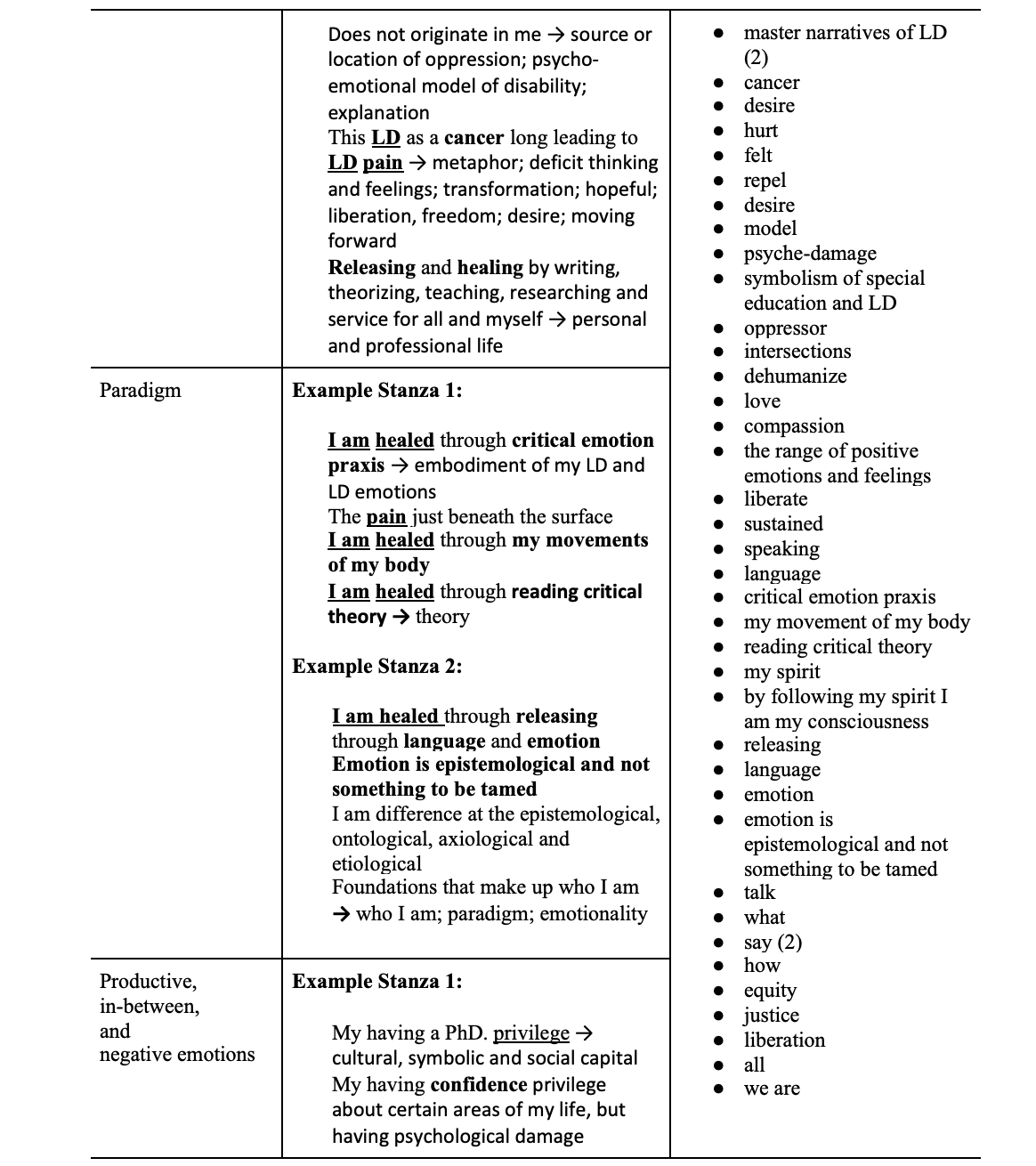

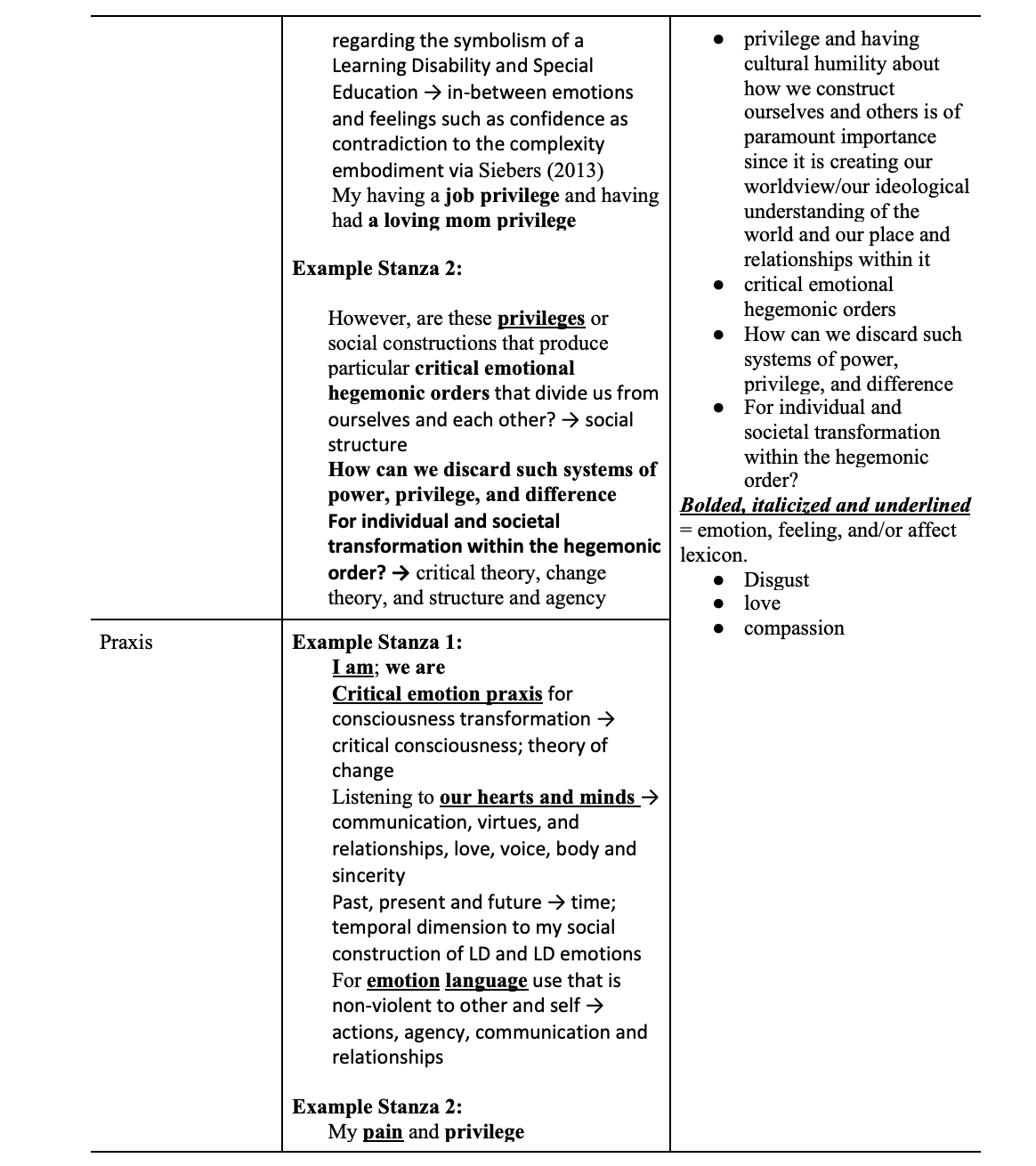

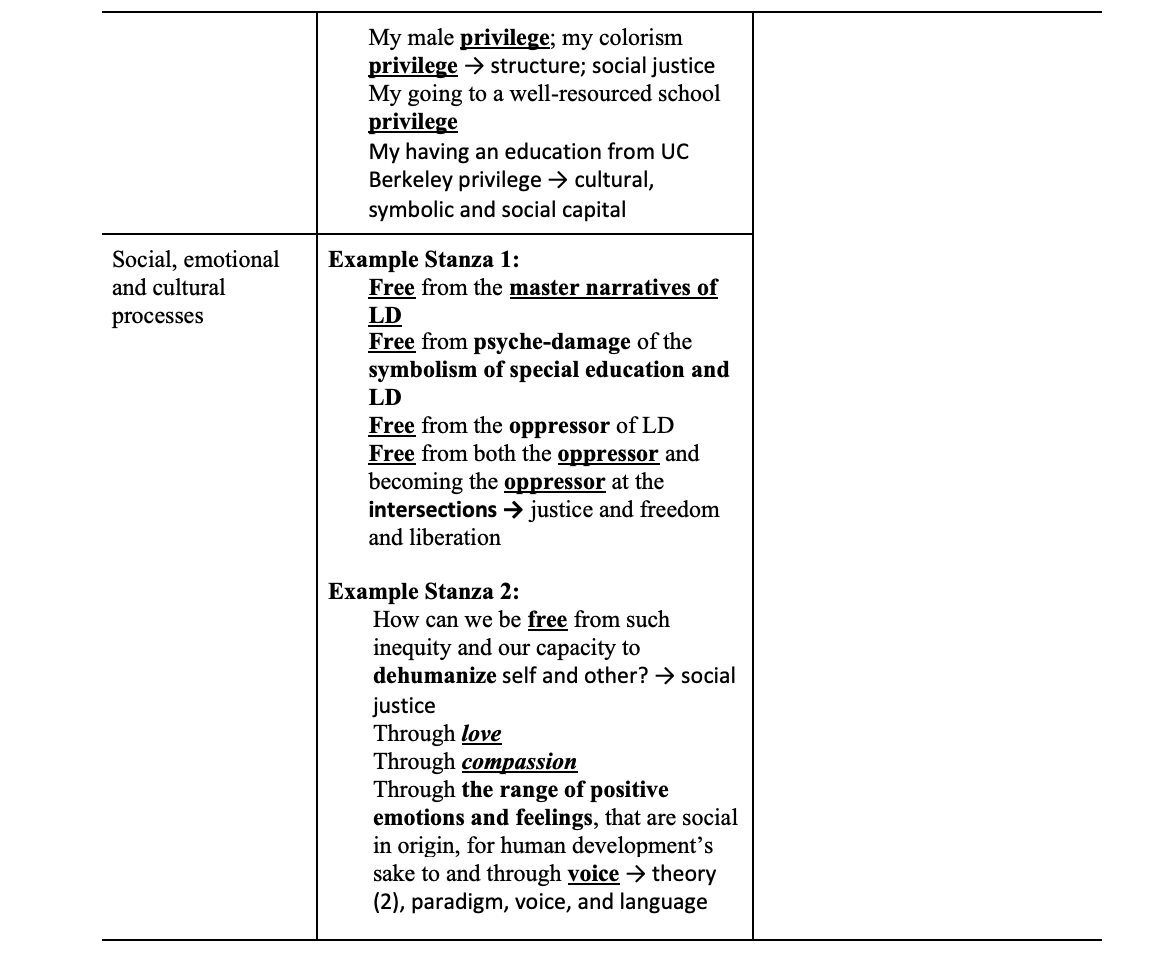

The study’s themes for Hernández-Saca’s presentation included: (a) spirit; (b) identity; (c) paradigm; (d) productive emotions as resistance, in between emotions as complexity, and negative emotions as oppression and embodiment; (e) praxis; and (f) social and cultural processes. Hernández-Saca created the following key to code the emotion implicative WHAT, repetitive words, intensifier, and emotion, feeling and/or affect lexicon in his poems.

Coding Key:

- Bolded and underlined = repetitive word

- Italicized = intensifier

- Bold = emotion implicative WHAT

- Bolded, italicized and underlined = emotion, feeling, and/or affect lexicon

See Appendix E for examples of the following themes: Emotion-Laden Narrative-Thematic Analysis and identification of the above codes across all three poems.

Spirit. By the theme, “spirit,” Hernández-Saca foregrounds not only the role of his own spirituality, but also the universal humanity of suffering and pain that was also communicated to the pre-service teachers. This theme corresponded to how Boskovich facilitated meaning-making through her problem-posing education about Hernández-Saca’s phenomenological LD at his intersections of identities and power situation. This theme included open and descriptive codes such as liberation, voice, identity, consciousness, healing, speaking back, their-story and release.

Identity. The theme “identity” foregrounds the salience of representation, intersectionality, the politics of location or identity politics, and stereotypes in Hernández-Saca’s phenomenology learning dis/Ability experiences in K-20 and beyond. This theme is critical, given that traditional literature in special education has de-coupled its labeling and classification systems about dis/Ability from any discussion of politics or culture. This disconnection sustains what Siebers (2013) calls the ideology of ability—the privileg-ing of the able-body and the basis by which humanness is determined—as a-cultural, a-identity or a-intersectional. This does a de-service to progressive movements towards inclusion.

Paradigm. By the theme “paradigm,” Hernández-Saca emphasizes the role that his perspective and history play and how he understood and continues to make meaning of his auditory Learning Dis/ability at his intersections of power and privilege. These included personal and professional, conceptual, material, symbolic, cultural, social, and relational resources. For example, Hernández-Saca’s theoretical knowledge of Dis/Ability Studies in Education served as a buffer against dominant epistemologies or ontological-epistemological erasure of the methodologies, dis/Ability theories, and critical emotion praxis framework that served as the foundation of his convictions and principles.

Productive, in-between, and negative emotions. Within the theme “productive emotions as resistance, in between emotions as complexity, and negative emotions as oppression and embodiment,” the role of the body, and the embodiment of emotions such as anger and disgust, movements of his body and spirit, and, more importantly, the catalytic anchor of love that mediated his phenomenological experiences with LD and special education. These raw materials represented my transcendence of my LD and special education emotional suffering. In other words, they represented my humanity coupled with my professional development as it relates to not only my voice as a person but also the facilitation of general and pre-service teachers’ voice toward inclusion.

Praxis. The theme “praxis” centers the importance of critical emotion reflectivity about my present, past, and future self and consciousness as it relates to my intersectional identities, both personal and professional. Open and descriptive codes within this theme included: critical consciousness, actions, communication, critical emotion praxis, voice, language, how we talk to one another, and ourselves and agency, among others. The notion of praxis comes from Freire’s (1974) theory and practice of critical consciousness, where he argued for a critical pedagogy that would allow the oppressed to liberate themselves from the myths and half truths of society. Goulet (2005) wrote the following:

Paulo Freire’s central message is that one can know only to the extent that one “problematizes” the natural, cultural, and historical reality in which s/he is immersed . . . problematize in his sense is to associate an entire populace to the task of codifying total reality into symbols which can generate critical consciousness and empower them to alter their relations with nature and social forces. (p. ix)

This phenomenological study has helped me take back my dignity and humanity from the discourses and materialities of LD and special education that served as a dehumanizing power in my psyche and quality of life.

Social, emotional, and cultural processes. In the theme “social, emotional, and cultural processes” Hernández-Saca highlights how intersectional “isms,” such as the ideology of ability, nativism, racism, English-only policies, and other forms of violence, worked to shape not only his perceptions and educational experiences of self and others but larger society and educational systems. Open and descriptive codes included: special education, labeling, classification, others’ opinions, relationships, how we talk to each other, history, time, power, structure, and agency. This theme also was mediated by the collective focus groups’ community building that Boskovich and Hernández-Saca engaged in with each other and the pre-service teachers as they facilitated the de- and re-construction of dis/ability identity at the intersections of power, privilege, and emotionality.

Discussion, Implications, and Conclusion

Discussion

The study’s main research question that guided our study focused on: How can the sharing of phenomenological LD experiences at their intersections of power and identities with preservice teachers impact their praxis of teaching? The conducting of this study had each Author reach inward and touch upon painful experiences, then illustrate the inherent power of both individuals to heal and grow through the writing of poetry and a reading of Boskovich’s thesis. Our research fills a gap within the Dis/Ability Studies in Education (DSE) literature and offers a new paradigm to teach, heal, and reach past the assumptions held of self that were socially, culturally, emotionally, and politically constructed.

Implications

Our lived critical emotion praxis, in turn, is our critical consciousness, as we shared our stories and emotionality as it related to LD. How we experienced LD served as the forum through which to re-feel and re-think the meaning of a learning disability in schools and society, the education process, and the impact of educational disability labels like LD at the intersections of power and historically multiply marginalized identities. Given the federal legislation of the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) and its implementation of the medical model and reliance on compliance (Voulgarides, 2018). It is of critical importance for all those diagnosed with an LD at their intersections of power and privilege to disrupt this policy-master narrative through their voices and the emotionality of all who have been labeled. This study has implications for not only pre-service teachers but for school counselors, administrators, and education faculty at universities as well.

It is now time to move beyond the technical dimensions for teacher learning and education at the boundaries of traditional special education and Dis/Ability Studies in Education teaching and training (Hernández-Saca et al, In Press). The implementation of a Dis/Ability Studies in Education paradigm is of critical importance to engender a critical emotion praxis for theory, research, policy, and practice in teacher education.

Conclusion

It is now time for a shifting in the way pre-service teachers are instructed. The cultural-historical, policy, and professional master narratives of what counts as “Learning Disabilities” (Hernández-Saca, 2016), can no longer be considered a medical-psychological and technical service delivery endeavor. Our lived phenomenological experiences have illuminated the intersectional, emotional, political, relational, social, and cultural construction of LD. Sharing our LD experiences at our intersections with both general and special educator and pre-service teachers is critical for developing their teacher voice through critical emotion praxis—the coupling of critical thinking and feeling before they act within educational systems (Artiles & Kozleski, 2007; Freire, 2000; Zembylas, 2005; 2015). Stepping into a classroom to teach is a multi-dimensional experience, one where a teacher’s body, spirit, heart, soul, and mind are involved. This praxis of teaching requires and asks much. It is our wish to impact not only the lives of future teachers but each individual who is in the pursuit of knowledge.

[1] By Dis/Ability, we underscore the social, emotional, political, historical, and economic construction of both disability and ability. When we leave “disability” or “disabilities” without the dash, we underscore the cultural-historical, policy and/or professional master narratives of learning disabilities institutionalized in education and global society (Hernández-Saca, 2016). These are opposed to the Dis/Ability Studies in Education conceptualization of what counts as dis/Ability in education and global society.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2013). Privileging and affecting agency. In C. Maxwell, & P. Aggleton (Eds.),

Privilege, agency and affect: Understanding the production and effects of action (pp. 240–247). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ahmed, S. (2004). Cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh University Press.

Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2008). Doing narrative research. Sage.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(1), 1-31. doi:10.1080/13613324.2012.730511

Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, E. B. (2007). Beyond convictions: Interrogating culture, history, and power in inclusive education. Language Arts, 84(4), 357-364.

Artiles, A. J., Thorius, K. K., Bal, A., Neal, R., Waitoller, F., & Hernández-Saca, D. (2011).

Beyond culture as group traits: Future learning disabilities ontology, epistemology, and inquiry on research knowledge use. Learning Disability Quarterly, 34(3), 167-179. doi:10.1177/0731948711417552

Arzubiaga, A. E., Artiles, A. J., King, K. A., & Harris-Murri, N. (2008). Beyond research on cultural minorities: Challenges and implications of research as situated cultural practice. Exceptional Children, 74(3), 309-327. doi:10.1177/001440290807400303

Au, W. (2017). The dialectical materialism of Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy. Reflexão e Ação, 25(2), 171-195. doi:10.17058/rea.v25i2.9814

Baker, B. (2002). The hunt for disability: The new eugenics and the normalization of school children. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 663-703. doi:10.1111/1467-9620.00175

Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36(4), 391-409.

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability oppression and empowerment. University of California Press.

Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49-51.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research. Meaning and perspective in the research process. Sage Publishing.

Dillard, C., & Okpalaoka, C. L. (Eds). (2013). Engaging culture, race and spirituality: New visions. Peter Lang.

Douglass, B. G., & Moustakas, C. (1985). Heuristic inquiry: The internal search to know. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 25(3), 39-54. doi:10.1177/0022167885253004

Edwards, D. (1999). Emotion discourse. Culture & Psychology, 5(3), 271-291.

Eisner, E. W. (1998) Does experience in the arts boost academic achievement. Arts Education Policy Review 100(1): 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632919809599448

Eisner, E. W. (2003). On the differences between scientific and artistic approaches to Qualitative Research. Visual Arts Research, 29(57), 5-11. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20716074

Ely, M., Vinz, R., Downing, M., & Anzul, M. (1997). On writing qualitative research: Living by words. Falmer.

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. University of Chicago Press.

Erevelles, N. (2011). Disability and difference in global contexts: Enabling a transformative body politic. Springer.

Erevelles, N., & Minear, A. (2010). Unspeakable offenses: Untangling race and disability in discourses of intersectionality. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies, 4(2), 127-146.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning: an introduction to logotherapy. Simon & Schuster.

Freedman, J. E. (2016). Disability Studies in Education (DSE) and the epistemology of special education. In M.A. Peters (Ed.). Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory (pp. 1-7). Springer.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 1968. Trans. Myra Bergman Ramos. Herder.

Freire, P. (1974). Education for critical consciousness. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gallagher, D. (2010). Hiding in plain sight: The nature and role of theory in learning disability labeling. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(2).

http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v30i2.1231

Gallagher, D. (2014). Exploring some moral dimensions of the social model of disability. In D. J. Connor, J. W. Valle, & C. Hale (Eds.). Practicing disability studies in education: Acting toward social change (pp. 19-34). Peter Lang.

Galvin, R. (2003). The making of the disabled identity: A linguistic analysis of marginalisation. Disability Studies Quarterly, 23(2).

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436-445.

Goulet, D. (2005). Introduction. In Freire education for critical consciousness. (pp. vii-xiii). Continuum.

Hedegaard, M. (2008). Studying children: A cultural-historical approach. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hedegaard, M., Edwards, A., & Fleer, M. (Eds.). (2011). Motives in children’s development: cultural-historical approaches. Cambridge University Press.

Hernández-Saca, D. I. & Cannon, M. A. (2016). Disability as psycho-emotional disablism: A theoretical and philosophical review of education theory and practice. In M. Peter (Ed). Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory (pp. 1-7). Springer Publishing.

Hernández-Saca, D. I., Gutmann Kahn, L., & Cannon, M. A. (2018). Intersectionality dis/ability research: How dis/ability research in education engages intersectionality to uncover the multidimensional construction of dis/abled experiences. Review of Research in Education, 42(1), 286-311.

Hernández-Saca, D., & Cannon, M. A. (2019). Interrogating disability epistemologies: towards collective dis/ability intersectional emotional, affective and spiritual autoethnographies for healing. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(3), 243-262.

Iqtadar, S., Hernández-Saca, D. I., & Ellison, S. (2020). ” If It Wasn’t My Race, It Was Other Things Like Being a Woman, or My Disability”: A Qualitative Research Synthesis of Disability Research. Disability Studies Quarterly, 40(2).

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problems and processes in human development. Harvard Press.

Labov, W. (1984). Intensity. In D. Schiffrin (Ed.), Meaning, form, and use in context: Linguistic applications (pp. 43-70). Washington DC: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics [Special Issue].

Lambert, L., Walker, D., Zimmerman, D. P., Cooper, J. E., Lambert, M. D., Gardner, M. E., Slack, P. J. F. (1995). The constructivist leader. Teachers College Press.

Lee, A.M.I. (2020). The 13 disability categories under IDEA. Understood.org.

Leggo, C. (2008). The ecology of personal and professional experience: A poet’s view. In M.

Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education (pp. 89-98). Routledge.

Lin, J., Oxford, R. L., Culham, T. E. (2016). Toward a spiritual research paradigm: Exploring new ways of knowing, research, and being. Information Age Publishing.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2013). The constructivist credo. Left Coast Press.

Mahn, H. (1999). Vygotsky’s methodological contribution to sociocultural theory. Remedial and Special Education, 20(6), 341-350. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259902000607

Moir, J. (2005). Moving stories: Emotion discourse and agency. Frontiers of Sociology, the 37th World Congress of the International Institute of Sociology, (1–19). Stockholm, Sweden.

Moran, M., (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge.

Moustakas, C. E. (1972). Loneliness and love. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Moustakas, C. E. (1975). The touch of loneliness. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Moustakas, C. E. (1990). Heuristic research: Design, methodology, and applications. Sage Publications.

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications.

Moustakas, C. E. (1995). Being-in, being-for, being-with. Jason Anders.

Nasir, N. S. (2011). Racialized identities: Race and achievement among African American youth. Stanford University Press.

Paul. J., Kleinhammer-Tramill, J., & Fowler, K. (2009). Qualitative research methods in special education. Love Publishing.

Phillips-Pula, L., Strunk, J., & Pickler, R. H. (2011). Understanding phenomenological approaches to data analysis. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 25(1), 67-71. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.09.004

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1991). Narrative and self-concept. Journal of Narrative & Life History, 1(2-3), 135-153. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.1.2-3.04nar

Prior, M. T. (2015). Emotion and discourse in L2 narrative research. Multilingual Matters.

Reindal, S. M. (2008). A social relational model of disability: Theoretical framework for special needs education? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 23(2), 135-146.

Reiners, M. G. (2012). Understanding the differences between Husserl’s (descriptive) and Heidegger’s (interpretive) phenomenological research. Journal of Nursing and Care, 1(5). 1-3. doi:10.4172/2167-1168.1000119

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

Russell, T., & Schuck, S. (2004). How critical are critical friends and how critical should they be? In D. L. Tidwell, L. M. Fitzgerald, & M. L. Heston (Eds.), Journeys of hope: Risking self-study in a diverse world. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices (pp. 213-216). University of Northern Iowa.

Saldaña, J. (2009). An introduction to codes and coding. The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 3. Sage.

Siebers, T. (2013). Disability and the theory of complex embodiment—for identity politics in a new register. The Disability Studies Reader, 4, 278-297.

Sultan, N. (2019). Heuristic inquiry, researching human experience holistically. Sage.

The BIPOC Project: A Black, Indigenous & People of Color Movement (n.d.). https://www.thebipocproject.org/

Thomas, C. (1999). Female forms: Experiencing and understanding disability. McGraw-Hill Education

Trahar, S. (2009). Beyond the story itself: Narrative inquiry and autoethnography. Intercultural Research in Higher Education, 10(1), 1-10. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1218/2653

Van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice. Routledge.

Vagle, M. (2014). Crafting phenomenological research. Routledge.

Voulgarides, C. (2018). Does compliance matter in special education? IDEA and the hidden inequities of practice. Teachers College Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University.

Wakeman, B. E. (2015). Poetry as research and as therapy. Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies, 32(1), 50-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265378814537767

Williams, P. (1987). Spirit-murdering the messenger: The discourse of finger pointing as the law’s response to racism. University of Miami Law Review, 42, 127.

Zembylas, M. (2005). Discursive practices, genealogies, and emotional rules: A poststructuralist view on emotion and identity in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 935-948.

Zembylas, M. (2015). ‘Pedagogy of discomfort’ and its ethical implications: The tensions of ethical violence in social justice education. Ethics and Education, 10(2), 163-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2015.1039274

Appendix A

Data Sources Across Semesters, SPED 4150 Sections and Participants

| Academic Semester and Course Section | # of Pre-service Teachers Participants | Questionnaire Respondents | Amount of Video Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2017 SPED Course Section 1 | 18 | 18 | 47 minutes and 35 seconds |

| Fall 2017 SPED Course Section 2 | 17 | 15 | 57 minutes and 26 seconds |

| Spring 2018 SPED Course Section 1 | 12 | 12 | 56 minutes and 3 Seconds |

| Spring 2018 SPED Course Section 2 | 18 | 7 | 40 minutes and 7 seconds |

| Fall 2018 SPED Course Section 1 | 8 | 5 | 1 hour, 14 minutes and 13 seconds |

| Fall 2018 SPED Course Section 2 | 11 | 5 | 45 minutes and 19 seconds |

| Spring 2019 SPED Course Section 1 | 12 | 4 | 54 minutes and 14 seconds |

| Spring 2019 SPED Course Section 2 | 13 | 3 | 1 hour, 4 minutes and 11 seconds |

| 8 Sections of SPED Course | 109 participants | 69 Respondents | 9 hours, 18 minutes and 8 seconds |

Appendix B

Pre-Questionnaire: Focus Group Guiding Reading and Class Discussion Protocol—Research Study (Section 1 or 2) (Term)

The purpose of this pre-questionnaire is to prepare you for class/focus-group discussion after I, Hernández-Saca, present my 3 poems about the emotional impact of LD.

The research question is for the larger study is:

1) How will the sharing of two educators’ phenomenological LD experiences with preservice teachers within a special education teacher course impact and influence their praxis of teaching through their written feedback and classroom dialogue?

Instructions:

1) Read Co-Lead Author 1’s or Co-Lead Author 2’s poems

2) Fill out this survey

Thank you, Co-Lead Author 1 and Co-Lead Author 2

1) What challenges do students face as a result of a Learning Disability Diagnosis?

2) How do students with a Learning Disability form their identity?

3) How is their process of identity formation impacting their social, emotional, and educational well-being?

4) How do preservice teachers interpret and connect with students who have Learning Disabilities?

5) How can preservice teachers view their students as whole individuals?

6) Any other questions, reflections, comments that you are wondering about?

Appendix C

Boskovich

Poems on: DISABILITY AND HEALING

October 17, 2013

Labeled

Test scores determined

An LD in Perceptual Organization.

What if the test scores were wrong?

What if they only represented a fraction of truth?

A slice of a fraction,

1⁄2 of a lie,

Wasn’t I a whole person?

How was that missed?

This inner question,

Persists.

Accommodations felt like separation.

Visual you are different.

Tests taken elsewhere set me apart.

I didn’t want to be separate.

But,

I needed quiet and more time.

Produced Deficit feeling.

DSPS advisor watching,

Through a closely guarded lens.

I was so much more,

Than a graph,

Representing LD test scores.

October 15, 2013

I am x-1

Smart = Segregated

And ≠

For smart Connotates (x)’s function I am x

≤ not ≥

Always Separated

2 groups

a class of 18

9 way split down the middle

9 factored

3×3

Both are prime numbers.

∴

There never was room for me. Smart Triggers

{ 0 } an empty set

Vulnerability

Fear

Self-loathing

And a Lifetime

Of being left out and not belonging. Smart hurts.

Smart meant ⊄ = (does not belong) Smart ordained

x-1,

I am x

November 8, 2013

Continuous Variable

For once there is no documented evidence,

No test scores,

No scatter plots or bar graphs,

To measure me against another.

No standard deviation away from the mean to compute.

No Mathematical Symbols My choice to define.

My choice to explain.

Just what it means to be me.

I claim my own self now.

I am my own Qualitative variable.

I am n-1 degrees of freedom.

The student’s t-Distribution.

I am my own measure of central tendency.

Not defined by anyone,

But by me.

My own Bell Shaped Curve.

Appendix D

Hernández-Saca

RESISTING LEARNING DIS/ABILITY OPPRESSION: HEALING THROUGH DIS/ABILITY VOICE

LD Pain

LD pain

Gripping my soul

Disgust

Yearning for release

LD pain

Stigma on the mind, body and soul

No longer ashamed to express it

For release of master narratives of LD

LD pain

Inside the body and my story

In the past, present and future

Core-identity hopeful

LD pain

Is real

Is a sociocultural construction

Healing through dis/ability as the psycho-emotional disablism model

LD pain

Anger

Mistrust

Needing to let go

LD pain

My journey towards healing

The importance of expressing your truth

To transform self and society

LD pain

Continuous

Communicated

Not heard

LD pain

“Just get over it”

“Stop being so sensitive”

Lost in other’s opinions

LD pain

Does not originate in me

This LD as a cancer long leading to LD pain

Releasing and healing by writing, theorizing, teaching, researching and service for all and myself

Speaking Back to LD Pain

Body, spirit, mind pain and hurt

So ever present

So ever felt

So ever that desire to repel

Desire turned into action

Action accomplished through will

Will to transcend and heal

Heal through presence that is not interpreted as the medical model, but the psycho-emotional disablism at work inside and outside of me

How can this theory turn into healing?

Theory and practice as praxis

Breathe as praxis that coupling of critical reflection and action

Towards speaking and being free

Free from the master narratives of LD

Free from psyche-damage of the symbolism of special education and LD

Free from the oppressor of LD

Free from both the oppressor and becoming the oppressor at the intersections

How can we be free from such inequity and our capacity to dehumanize self and other?

Through love

Through compassion

Through the range of positive emotions and feelings, that are social in origin, for human development’s sake to and through voice

Voice

Voice

Voice

What is voice?

How can voice help liberate me?

How can voice be sustained?

How can voice relate to language and freedom?

How can voice facilitate: “Nothing about Us Without Us”?

“Nothing about Us Without Us”

I have been speaking back

Internally

Externally

No more!

No more!

No more!

(I am) speaking back to LD Pain

How Can I Heal?

My body and mind and spirit are connected

I am healed through theory

I am healed through being myself

I am

I am healed through my utterances

I am healed through listening

I am healed through music

I am healed through my ways through words

I am healed through critical emotion praxis

The pain just beneath the surface

I am healed through my movements of my body

I am healed through reading critical theory

I am healed through allowing my words to express how I feel

I heal through teaching

I am healed by following my spirit

By following my spirit I am my consciousness

I am healed through releasing through language and emotion

Emotion is epistemological and not something to be tamed

I am difference at the epistemological, ontological, axiological and etiological

Foundations that make up who I am

How we talk to each other matters

What we say and how we say it at the emotions and language

What we say to ourselves, not in an individualistic way that reinforces the medical model

But a psycho-emotional disablism that is cognizant of the intersections

The intersectional dis/Ability discourses at the structural level

How we make feeling-meaning making together

How we love each other and ourselves for equity, justice and liberation

For all

I am; we are

Critical emotion praxis for consciousness transformation

Listening to our hearts and minds

Past, present and future

For emotion language use that is non-violent to other and self

My pain and privilege

My male privilege; my colorism privilege

My going to a well-resourced school privilege

My having an education from UC Berkeley privilege

My having a PhD. privilege

My having confidence privilege about certain areas of my life, but having psychological damage regarding the symbolism of a Learning Disability and Special Education

My having a job privilege and having had a loving mom privilege

My having loving brothers and sisters privilege

My having gotten my US citizenship privilege

Having privilege and having cultural humility about how we construct ourselves and others is of paramount importance since it is creating our worldview/our ideological understanding of the world and our place and relationships within it

However, are these privileges or social constructions that produce particular critical emotional hegemonic orders that divide us from ourselves and each other?

How can we discard such systems of power, privilege, and difference

For individual and societal transformation within the hegemonic order?

Appendix E

Appendix F

On Narrative Writing and Poetry