Integrating Disability Studies Pedagogy in Teacher Education

By Justin Freedman, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Rowan University

Amy Applebaum, M.A.

Doctoral Student, Syracuse University

Casey Woodfield, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor, Rowan University

& Christine Ashby, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, Syracuse University

Abstract

Within the larger interdisciplinary field of disability studies, a growing contingent of critical special educators have sought to disentangle disability from medicalized conceptions that have long predominated in the research and practice of schooling. Many of these scholars are also teacher educators and uniquely positioned to introduce disability studies to their postsecondary students. In this paper, we review and evaluate two decades of research literature at the intersection of disability studies and teacher education. We seek to answer the following question: What pedagogical approaches have colleagues used to introduce disability studies to teacher education students through programmatic and curricular revisions, and with what results? We first review foundational contributions in research literature that establish the purpose and precepts of disability studies in teacher education courses. Then we review research of the application of approaches aligned with disability studies within teacher education programs and course curricula. We conclude by evaluating the use of disability studies in teacher education and suggesting future directions for research and practice.

Keywords: disability studies, teacher education, curriculum, research, pedagogy

Understanding and documenting the evolution of a field can provide an opportunity to reflect, identify patterns, and lay a path for moving forward. Disability studies as a field of inquiry centers on examining disability as a form of diversity and an experience constructed between an individual and their social, political, and cultural environment. In 1999, a group of special education and disability studies scholars formed a special interest group in the American Education Research Association, formalizing disability studies in education[2] as a distinct research field with a specific focus on applying DS tenets to the context of schools (Baglieri, Valle, Connor, & Gallagher, 2011). Like other disability studies scholars in the humanities, social sciences, and law, these scholars study the sociocultural aspects of disability, though with a specific focus on the relationship between disability and education systems in the United States, and internationally (Connor, Valle, & Hale, 2012). As Connor, Gable, Gallagher, and Morton (2008) explain, the mission of disability studies in education “is to promote understandings of disability from a social model perspective…to challenge medical, scientific and psychological models of disability as they relate to education” (p. 447).

This interest in disability and schooling alignwith research and practice in the fields of special education and teacher education.As Connor (2012) write, “Many of us work as professors in special education teacher programs. We are integral parts of the operations that contribute to molding special education teachers and, as such, are actually in potentially powerful positions at a vital point in the production line” (p. 9). Yet, disability studies informed teacher educators have adopted theoretical and ideological perspectives that critique and resist predominant approaches to special education, leading some to identify their work as ‘critical special education’ (e.g., Ware, 2005, p. 104). As did the work of early disability studies scholars who were critical of medicalized responses to disability (e.g., Zola, 1976), disability studies informed teacher educators have challenged the “expert discourse” of special education that elevates professional opinion over the experiences of individuals with disabilities and their families. They also refute that disability is an undesirable characteristic requiring a specialized form of remedial instruction that is wholly different from the instruction of nondisabled peers (Baglieri, Valle, et al., 2011).

Working in professional teaching certification programs offers a unique opportunity for teacher educators to introduce pedagogical approaches that align with disability studies into the structures and curriculum of courses. Yet integrating DS approaches in teacher education presents challenges. Ferri (2006) noted several challenges to “operationalizing a disability studies approach to teacher education,” including a limited number of education textbooks and readings that offer perspectives from disability studies, curricular restrictions created by traditionally accredited teacher certification programs, a lack of previous models for how to integrate disability studies into entrenched curriculum, and a lack of like-minded colleagues with whom to ally. Cosier and Pearson (2016) found that some disability studies informed teacher educators have reported feeling isolated when working with colleagues who are often either unaware of DS or view the field as synonymous with special education. Another challenge has emerged as a number of states in the United States now require that teacher candidates complete the Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA) to become a certified teacher, which requires an individualized and deficit-based approach to disability (Bacon & Blachman, 2017).

Over the past two decades, dozens of research articles and book chapters have been published describing disability studies pedagogical approaches in teacher education. In this paper, we seek to recognize the contributions of researchers and synthesize the methods and results of their work. Further, we will evaluate the application of disability studies pedagogies in teacher education, and suggest future directions for research and practice. We begin by providing an explanation of our methods for identifying research literature.

Identifying Research at the Intersection of Disability Studies and Teacher Education

To identify research at the intersection of disability studies and teacher education, we conducted periodic searches for peer-reviewed research, monographs, and individual book chapters dating back to 1999, the year disability studies in education was formally founded (Baglieri, Valle, et al., Our initial criteria were: (a) peer-reviewed journal articles or published books/book chapters; (b) the key terms used in disability studies (with or without the term education) and at least one of the following: “teacher education,” “teacher preparation,” “teacher educators,” “teacher candidates,” or “preservice teachers”; (c) publication between the years 1999 and 2019.

Beginning in the fall of 2016, using the following methods we collected research literature by:

- searching major databases including ERIC, PubMed, and Google Scholar, using our key terms,

- searching these key terms within the following DS aligned peer-reviewed journals: Canadian Journal of Disability Studies; and Disability & Society; Disability Studies Quarterly; International Journal of Inclusive Education; Review of Disability Studies,

- searching the table of contents and of books within the Disability Studies in Education book series published by Peter Lang,

- making informal requests to colleagues for recommendations, and

- reviewing resources shared by colleagues through social media and listservs.

We repeated these methods approximately every six months until we concluded our literature collection in January 2019.

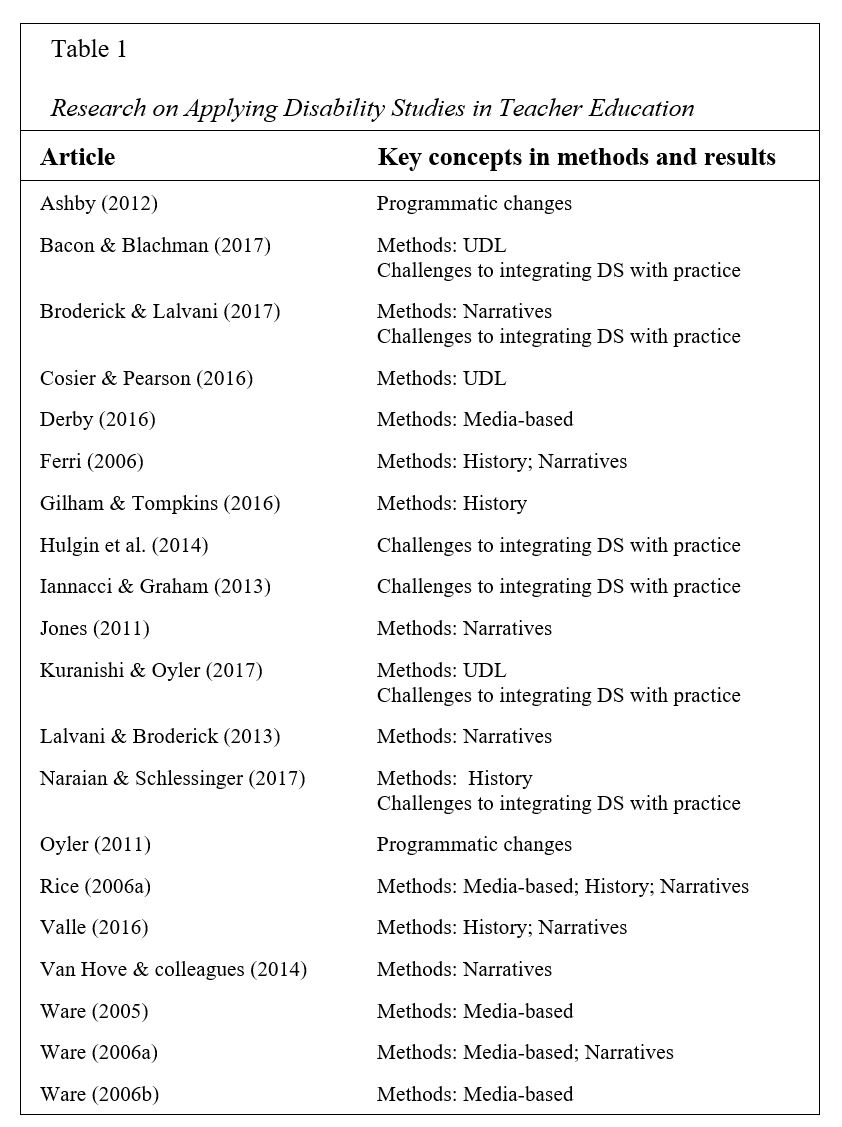

After collecting initial and follow-up rounds of literature, we applied stricter inclusionary criteria. First, several articles and book chapters mention teacher education in passing, but the focus of the research is K-12 schooling. Second, many of the sources included a sustained discussion of theoretical concerns of disability studies approaches, but did not provide examples of how DS had been introduced and applied within teacher education. Therefore, we narrowed the inclusion of research to the application of disability studies in teacher education through practice, such as pedagogical approaches used in individual courses, or alterations to the programs or structures of teacher education. The first and second authors conferred to reach agreement in instances in which there was uncertainty or disagreement about whether a source should be included. In the end, as shown in Table 1, we identified 20 sources as research on application, most of which involve empirical data collection.

Theoretical Aims of Disability Studies in Teacher Education:

Before reviewing this research, we provide a brief overview of the theoretical aims of infusing disability studies into teacher education, using several sources from our initial collection of literature that did not meet our final criteria of application to practice. The first two subsections address key theoretical frameworks in the field of disability studies – critical analysis of a medical model of disability, and inclusive pedagogy. The third subsection reviews some of the challenges that have emerged in response to efforts to integrate these theoretical frameworks into teacher education.

Challenging Medicalized Constructions of Disability

A frequent goal of researchers seeking to infuse disability studies into teacher education is to challenge the theoretical underpinnings of disability within the field of special education. As Allan (2006) asserts, there has been a “dominance in teacher education by special education,” and working within a disability studies framework can unravel the knowledge base of special education. The most frequent critique is the medicalized approach to disability (p. 349). Rice (2006a) argues that the medical model is espoused “almost exclusively to future teachers” and describes its role in teacher education:

Teacher Education in special education typically focuses on identifying characteristics of various disabilities and promoting ‘best practices’ for intervention and remediation. ‘Disabilities’ are presented as discrete side within students and are detected by experts through test scores, observations, checklists and the like. (Rice, 2006a, p. 251)

Mutua and Smith (2006) assert that a medicalized approach to disability encourages pre-service teachers to view disability as an individual deficit and to “not consider or take seriously alternative conceptualizations” (p.127).

Rice (2006b) describes disability studies as a “site of resistance” to ideas about disability and education that are presented as neutral or commonsensical within a medicalized approach in teacher education (p.17). Rice (2006a) describes a DS approach in teacher education as a cultural, historical, and political phenomenon that is exacerbated by ableism inherent in systems and structures of schooling. Cosier and Ashby (2016) assert that introducing disability studies can encourage teacher candidates to examine the social barriers that deny students meaningful participation in general education, such as by critically examining how a medicalized perspective often leads to more restrictive environments.

Researchers have commonly attributed differences between DS and special education approaches to their different disciplinary roots. Special education developed from behavioral psychology, medicine, and psychometrics, whereas disability studies aligns more with sociological and sociolinguistic frameworks that emphasize the learning context, rather than remediation of individual skills (Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling, 2012; Danforth & Naraian, 2015). The theoretical framework of special education is evident in textbooks used in teacher education, which Brantlinger (2006) and Freedman (2016) have found to rely exclusively on medicalized characterizations of disability. DS-informed teacher educators emphasize the use of a plurality of perspectives toward disability that shift the focus from the individual to the environment, through the development of inclusive education (Baglieri, Bejoian, Broderick, Connor, & Valle, 2011).

Defining and Promoting Inclusive Pedagogy

In looking to the context rather than the individual, disability studies informed teacher educators seek to encourage their students to become both critical and inclusive educators. Inclusion is a contested term that has evolved over decades. As Oyler (2011) writes, “No single word in the history of special education may have as many meanings as the term inclusion” (p. 5). Inclusion is often associated with special education and commonly refers to the extent to which a student identified with a disability is educated alongside nondisabled peers. DS scholars have expressed concerns about the limitations of current legal frameworks for encouraging inclusion. Under federal law in the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Improvement Act (IDEIA, 2004), students with disabilities are expected to be educated with nondisabled peers, “[t]o the maximum extent appropriate.” Yet, despite implicitly encouraging inclusion through Least Restrictive Environment, the law maintains the “medicalized notion of disability” by requiring that students be labeled with a particular deficit-based disability in order to receive services (Cosier & Ashby, 2016, p. 26).

Recognizing the legal limitations for promoting access to general education, teacher educators have sought to disentangle inclusion from special education (Danforth & Naraian, 2015) and reassert it as a broader imperative, “concerned with aspirations for democratic and socially just education” (2011). While a key goal of inclusion remains “minimal or no segregation into special education classrooms or services” (Connor et al., 2008, p. 445), the notion of inclusion in DS goes well beyond location (Artiles & Kozleski, 2016). As Sapon-Shevin (2003) writes, “(I)nclusion is not about disability, nor is it only about schools. Inclusion is about social justice. Inclusion demands that we ask, ‘What kind of world do we want to create and how should we educate students for that world’ ” (p. 26)?

Inclusion is commonly described as transformation. Artiles and Kozleski (2016) write that inclusion within disability studies is an “ambitious project of educational transformation” as opposed to an incremental improvement over current special education practices. Rice (2006b) describes teacher candidates as potentially transformative figures, and Danforth (2014) writes that teacher candidates should adopt the perspective of teaching “against the grain” (p. 7). Broderick and Lalvani (2017) discuss the importance of teacher candidates understanding, “school inclusion as a vehicle for equitable, socially just education and broader cultural and societal change” (p. 896). Changing teacher candidates’ attitudes toward disability and schooling, according to Rice (2006b), requires a degree of unlearning of internalized ableism. Taken together, the literature reflects widespread belief that if teacher candidates are, “shaped by, and grounded in [disability studies in education]” (Connor et al., 2012, p. 9), they can become agents of cultural and pedagogical changes in their schools and society at large (Danforth & Naraian, 2015).

Challenges to Integrating Disability Studies in Teacher Education

Researchers have also identified tensions and challenges associated with integrating disability studies into the curriculum of teacher education. Not only are sociocultural theories of disability in tension with medicalized approaches to special education, but they are also largely absent from general education teacher education. The social justice frameworks used to critically examine other identity categories in general education courses typically do not include disability. Amidst the widening recognition that dis/ability is always a gendered and racialized phenomenon, scholars are increasingly proposing theoretical and conceptual frameworks, which integrate disability studies and critical theories used in general education teacher education.

Bialka (2015) suggests the use of a “critical ability theory” across teacher education to support teacher candidates to interrogate their disposition toward disability and acknowledge their able-bodied privilege. “Just as educators must consider their own racial identity when working with students of color,” Bialka (2015) writes, “it is also important that they attend to their physical and cognitive identities” (p.148). Similarly, Crawford and Bartolomé (2010) argue that teacher candidates must examine their “uncontested beliefs about normalcy” that can perpetuate discriminatory practices toward students of color, including disproportionate identification of disability and segregated special education placements (p. 166). Kulkarni (2019) has proposed an adaptation of Banks’ (2016) multicultural model to address disability, demonstrating how an enduring framework of general education teacher education can inform disability studies.

Another challenge for integrating DS in teacher education is the disconnect between disability studies and the practices teacher candidates encounter in field experiences. Training in inclusive pedagogy is likely to conflict with the legal and instructional frameworks of special education, which reflect medicalized approaches to disability (e.g., requiring students to be labeled with a specific disability in order to receive services) (Cosier & Ashby, 2016). Recognizing this tension, Heroux (2017) argues that a social model of disability in teacher education should be used “as a way to interrogate and challenge the assumptions inherent in a medical perspective of disability,” but not as a replacement to teaching medicalized approaches (p. 8). Examining the challenges and consequences of introducing theoretical frameworks that contradict entrenched school practices is a central aim of empirical research discussed in the next section.

Applying Disability Studies: Infusing Pedagogical Approaches in Teacher Education

Using the principles of inclusive education, teacher educators have introduced disability studies into the local contexts in which they work. We examine contributions to the broader structures and goals of individual teacher education programs, and review the pedagogical approaches these researchers have applied.

Restructuring Programs and Redefining Goals

Efforts to alter structures of teacher education programs reflect in many ways the theoretical aims of challenging traditional orientations toward disability that underpin general and special education. There is typically little collaboration between faculties or overlap in content between general and special teacher education programs, with the exception of an introductory course on special education required for general education teacher candidates (Blanton & Pugach, 2011). An underlying assumption of these programs is that the work of general and special education teachers is distinctly different, each requiring a specific knowledge base and set of skills to prepare for the profession. Debates between researchers about the appropriateness of maintaining separate programs go back to at least the 1980s (e.g., Pugach, 1988; Stephens, 1988). As students with disabilities increasingly accessed general education classrooms in the 1990s, several teacher education programs began to partially integrate or fully merge their curricula, ten of which are detailed in a book edited by Blanton, Griffin, Winn, and Pugach (1997).

Over the past two decades, some teacher educators have explicitly linked efforts to break down the structural divide between general and special education teacher preparation in accordance with the tenets of disability studies. Cosier and Ashby (2016) argue that discrete teacher education programs promote a medicalized view in which ability and disability are portrayed as binary, rather than as a spectrum of needs. The significance of this conceptual divide, they argue, is that it encourages the maintenance of segregated placements for students, as teachers are less likely to work to foster meaningful participation for students they feel are ill-prepared to teach.

Oyler (2011) and Ashby (2012) offer examples of two teacher education programs in the United States whose faculties have explicitly drawn on disability studies to frame the merging of their general and special education programs. Oyler (2011) provides an overview of the structure of a master’s degree program in inclusive elementary education at Columbia University’s Teachers College. Faculty there collaborated on creating a program that includes an option to pursue a dual certification in both elementary and special education in New York State. Oyler describes how the program faculty members’ “philosophical, curricular, and pedagogical decisions” are “grounded in our shared commitment to a disability studies/disability rights orientation,” and intended to foster teacher candidates who will embrace difference and reject expectations of normalcy (p. 12). Further, Oyler emphasizes the intersectional approach to the curriculum, with the goal of graduates being “able to detect and change school practices that help create the disproportional representation of African American and Latino males as qualified for special education services, and placed, again disproportionally, in the most segregated settings” (2011, p. 13).

Ashby (2012) provides another example of a disability studies informed teacher preparation program: Syracuse University’s undergraduate inclusive elementary and special education program. This program was developed by faculty in the early 1990’s and has since offered only a dual certification track designed for students to apply for both elementary and special education certifications. While faculty members at the time did not formally use the term disability studies to describe the merged program, Ashby illustrates how key tenets thread through curriculum. Examples include commitments to social justice, universally designed instruction, and disability as a sociocultural phenomenon. Ashby describes how the program’s disability studies influence provides a focus for teacher candidates to critically examine and challenge entrenched school structures and practices traditionally promoted in special education. Summarizing the role of disability studies in the program, Ashby writes that it “is not intended as a replacement for special education. Rather, it provides discursive tools for making sense of disability, and engaging in the critical conversations necessary to re-envision education for all” (p. 98).

Naraian and Schlessinger (2017) provide an overview of a secondary inclusive education graduate program at in the Northeastern United States. The program is intended to lead to a certification in secondary special education and prepare teacher candidates to teach in urban settings. One of the goals of the program is for students to develop “a praxis of critical inclusivity enacted from a DSE framework” (p. 84). Three courses within the program are explicitly designed to integrate disability studies with inclusive education. The authors highlight one of these courses, “Disability, Exclusion and Schooling,” which introduces teacher candidates to the social model of disability and is intended to “disrupt notions of ‘normal’ and explore the intersectionality of exclusion with a focus on ability” (p. 85).

Together, the examples offered by Oyler (2011), Ashby (2012), and Naraian and Schlessinger (2017) demonstrate the work of teacher educators to develop and evolve programs in alignment with disability studies. Teacher educators have strategically worked toward preparing teacher candidates who will advocate for and enact inclusive education in schools. Meanwhile, state certifications for special and general education teachers remain separate; there is no inclusive teacher certification. By merging programs and offering the option to pursue dual certifications, teacher preparation programs can resist traditional structures by creating an institutionalized expectation that their graduates will be prepared to teach all students.

Integrating Disability Studies into Curricula

Beyond the programmatic level, many teacher educators have introduced disability studies through individual course curricula. In this section, we review specific pedagogical approaches and include empirical results (e.g., student responses) when available. Students who enroll in these courses are typically matriculating into special and/or inclusive education teacher preparation programs at the undergraduate or graduate level. Other courses are designed for students matriculating in general education (i.e., elementary and secondary education) to take a single, required course in special education (Blanton & Pugach, 2011).

Tracing the history of disability. One pedagogical approach used by teacher educators is to ask students to investigate the history of disability and special education. Valle (2016) argues that for teacher candidates to develop critical outlooks on the special education system they must investigate the historical genealogy of practices. Doing so, Valle asserts, can help teacher candidates to better consider the context of current practices, such as the unequal power dynamics faced by parents in their relationships with teachers.

Gilham and Tompkins (2016) explain how they reconceptualized the curricula of two inclusive education courses, with an increased focus on the history of disability. Their revised curricula included a critical history of the medical model in which teacher candidates were introduced to eugenics and intelligence testing by exploring a website that makes connections between past and present eugenic ideas. Ferri (2006) asks teacher candidates to present about the history of disability across several eras and construct a timeline as a means of recognizing historical patterns in the attitudes and treatment of people with disabilities. Ferri also asks secondary general education teachers to brainstorm strategies for integrating disability into the curriculum of their content area, such as including disability narratives in an English literature class. Ferri shares that students commonly express enthusiasm about studying disability history for the first time, and exploring ways to integrate disability into their curricula. One student reflected that if more teachers learned and taught about the disability rights movement, they would be “less likely to see people with disabilities as helpless and in need of lower standards” (Ferri, 2006, p. 297).

Interdisciplinary and media-based approaches. Teacher educators report using interdisciplinary approaches, most commonly by integrating humanities-based disability studies into the curriculum. Ware (2005) has argued for infusing humanities perspectives across disability studies, including in education, as a cultural lens with which “to more fully understand disability, and therefore, to teach more rich and varied accounts of living with disability” (p. 112). Ware (2006a) describes conducting class activities including having students write about their earliest memories of disability, and analyzing the representation of disability in films. Through observing class discussions and analyzing assignments, Ware (2006a) concluded that a humanities-based approach helped teacher candidates to develop an understanding of disability through cultural lenses, as evidenced by students questioning taking for granted assumptions about independence, rethinking their interactions with people with disabilities, and questioning institutionalized ableism in schools that pathologize children.

Ware (2006b) elaborates on course activities that were used to counter the reductionist view of disability offered by special education, such as a narrow understanding of students based on medicalized labeling. For example, Ware describes asking teacher candidates to read the novel, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime by Mark Haddon, and then write an Individualized Education Plan that reflects a view of the protagonist across the novel. Ware suggests that this activity helped teacher candidates to create a more nuanced description of a student, as opposed to focusing on characteristics that are consistent with a disability label (i.e., autism spectrum disorder). In a course for art education teacher candidates, Derby (2016) describes integrating DS readings and asking students to complete a lesson plan using ableism as a lens for examining representations of disability in art. Derby found that despite having no prior exposure to disability studies, students were able to apply DS by “critiquing aspects of ableism,” such as “the able/not able constitutional divide” (p. 117). However, some students reinforced ableist values in their projects, and did not recognize their complicity in perpetuating these attitudes (Derby, 2016).

Infusing first-person narratives. Several other teacher educators have described using similar approaches, though with particular emphasis on first-person narratives. In shifting the design of introductory courses for general and special education teacher candidates, Ferri (2006) highlights the “interconnectedness of issues of disability, race, class, gender and sexuality,” which includes using autobiography, narrative, and fiction (p. 291-292). Ware (2006a), Ferri (2006) describes asking students to write about their earliest memories of disability. Ferri reports that this activity elicits several types of responses, such as students’ connections to family members or friends with disabilities, sharing their own disability identities, noting the distance between themselves and students with disabilities throughout their K-12 schooling, or even questioning whether their memories are “really” about disability. Ferri argues that this discussion helps students begin to deconstruct disability and recognize it as an elastic category that reveals as much about our sociocultural context as it does about embodied differences.

Jones (2011) provides further support for the use of first-person narratives in cultivating nuanced understandings of disability. Jones reviewed eight years of teacher candidates’ responses to narratives of individuals identifying with learning disabilities and mental health disorders. Students expressed an increased awareness of the lived experiences of people with disabilities and connected this understanding to teaching by advocating for practices to support diverse learners. Offering another approach emphasizing first-person perspectives, Van Hove (2014) detailed an assignment asking teacher candidates to partner with university students who received disability-related accommodations. Together, they created portraits that reflected the students’ self-representations. Finally, Valle (2016) emphasized incorporating narratives from both parents and siblings with disabilities, to encourage teacher candidates to examine the cultural meanings of disability and to alter their negative perceptions toward parental involvement in the education of their children. Valle found this pedagogical approach resonated with teacher candidates who were themselves mothers of children with disabilities, by providing a more genuine depiction of how parents must advocate for their children in the context of special education.

Lalvani and Broderick (2013) describe taking a critical approach to how the first-hand experience of disability is represented. In a graduate course for special education teacher candidates, the authors examined students’ attitudes toward using disability simulations to teach children about disability (e.g., wearing sight-impairing goggles to simulate blindness). Students were asked to read accounts of the use of disability simulations in schools and participate in a simulation in class. In comparing written reflections from the beginning and end of the semester, Lalvani and Broderick found that students initially viewed disability simulations as a means to raise awareness about the “challenges” of being disabled and to teach children about diversity (p. 475). However, by the end of the semester, the students had come to see disability simulations as insulting to people with disabilities and as highlighting individual deficits rather than social obstacles that disabled individuals.

Universal design for learning. Teacher educators have also introduced Universal Design for Learning (UDL), as a pedagogical approach for developing inclusive curriculum. Baglieri, Valle, et al. (2011) describe UDL as a framework for planning, teaching, and learning that blurs the boundaries of dis/ability by presuming “that all students possess unique sets of strengths and needs” (p. 272). Disability studies, according to Cosier and Pearson (2016), provide the rationale for using a framework such as UDL to guide teaching. However, learning about UDL without a theoretical backing could lead teacher candidates to view UDL as just another set of strategies. Instead, connecting UDL with disability studies theory can help to frame the importance of UDL using a social model of disability. When contextualized within a sociocultural understanding of disability, UDL approaches remove barriers to learning by planning for diverse learning needs, with the goal of providing marginalized students with access to general education curriculum (Cosier & Pearson, 2016).

Tensions and Challenges

Broderick and(2017) write that a central purpose of integrating a disability studies approach in teacher education is for teacher candidates to evolve their perspectives about disability and unlearn, “the presumed naturalness of traditional special education practices” (p. 897). Teacher educators have documented mixed results regarding the extent to which disability studies encourages teacher candidates to understand socially constructed aspects of disability and to recognize ableism in educational policy and practice. Rice’s (2006a) study of secondary education teacher candidates provides insight into some of the tensions and challenges in attempting to foster DS perspectives. Rice developed a course using approaches such as assigning readings and in-class activities about historical and media representations of disability and autobiographical accounts of individuals with disabilities. Through interviews and analysis of assignments, Rice found that: (a) students drew from both personal experiences and course materials to reconsider the meaning of disability; (b) teaching from a disability studies perspective brought forth the tensions between inclusive education and the structures of high schools; (c) teacher candidates expressed discomfort with the idea of advocating for inclusion because it appeared to be too political.

In a study of elementary education teacher candidates, Iannacci and Graham (2013) analyzed the perspectives of teacher candidates toward students with disabilities, before and after degree completion. Their program sequence featured one special education course rooted in disability studies. The researchers found that, despite their approach, DS perspectives “seemed to be abandoned when teacher candidates were immersed in school cultures that entrenched institutionalized ways of defining and knowing students with special needs….” and reiterated many of their initial understandings of disability (Iannacci & Graham, 2013, p. 27). The authors suggest that introducing disability studies in teacher education may be limited in encouraging teacher candidates to resist dominant discourses of disability, especially if DS pedagogy is isolated within a single-course curriculum.

Hulgin, O’Connor, Fitch, and Gutsell’s (2014) study of a DS grounded teacher education course provides further evidence of the difficulty of creating dissonance in students’ thinking about disability. From analysis of students’ assignments and observations of class discussions, the authors found that while some students began to question the practices and language of special education, others reacted to disability studies with “notions of objectivity, personal blame, and individualism,” and a distancing from issues of systemic oppression and schooling (para. 22). Hulgin et. al. conclude that a disability studies informed course must better engage with the individual identities of students, such as by linking disability to other forms of oppression (gender, race, sexual orientation) that will resonate with the unique and intersectional positionality of students.

Broderick and Lalvani (2017) describe an effort to understand how teacher candidates in a graduate special education course think about ableism. The authors expand upon King’s (1991) notion of “dysconscious racism,” an attitude that is both, “created by and supports mainstream ideology” (Broderick & Lalvani, 2017, p. 895), to include ableism. In their analysis of student definitions of disability and explanations of segregated educational settings, Broderick and Lalvani looked for evidence of “an impaired or distorted way of thinking about dis/ability…that tacitly accepts dominant ableist norms and privileges” (p. 895). They found that students’ understanding of disability as socially constructed, and of the role of ableism, was extremely limited at the end of the course. The authors conclude that these results are exacerbated by the absence of discussion about ableism in other critical approaches in teacher education including “critical multiculturalism and other facets of social justice education” (Broderick & Lalvani, 2017, pp. 902-903).

Another challenge faced by teacher educators is aligning DS perspectives in curriculum with state certification assessments, such as the Teacher Performance Examination (edTPA). Teacher candidates who responded to Bacon and Blachman’s (2017) survey reported that they needed to alter their teaching to accommodate the assessment, including by focusing on the needs of one particular student, as opposed to, “an inclusive approach to planning where individual needs are met and embedded into the general education curriculum and classroom” (Bacon & Blachman, 2017, p. 282). When analyzing why one student from a DS-oriented teacher education program failed the edTPA, Kuranishi and Oyler (2017) point to a number of conflicts between the exam’s rubric and the program’s core tenets, including the emphasis in the edTPA handbook on students with disabilities requiring distinctly different interactions, as opposed to universally designed instruction.

Teacher candidates’ poor performance on edTPA was also the impetus for Naraian and Schlessinger’s (2017) analysis of how teacher candidates drew on a social model of disability to understand their experiences in school. In reviewing student responses to course assignments, the authors found that being introduced to a social model helped teacher candidates to recognize patterns of oppression across multiple identity groups, and to critique the negative consequences of disability labeling in schools. However, they also found repeated instances of tension related to the divide between the ideals of a social model of disability and the experiences of teacher candidates in schools. Noting other DS scholars who have critiqued social constructionist approaches to disability, Naraian and Schlessinger argue that teacher candidates need to be introduced to a social model of disability that recognizes the embodied aspects of disability, as well as the variability of the experience of disability among teachers, parents, and students in schools.

Discussion and Future Directions of Teaching Disability Studies in Teacher Education

Allan (2006) cautioned against representing the field of disability studies in education, “as if it has a life of its own” (p. 347), suggesting that scholars devote work to “Talking about ourselves,” with “a recognition of our own capacities to act and think strategically about how—and where—we might do disability studies in education” (p. 348). While there are no recipes for a pedagogy aligned with disability studies in teacher education (Ferri, 2006), there are clear patterns in the pedagogical approaches teacher educators have used to resist the dominance of the medical model. Teacher educators draw on humanities-based approaches, encouraging a more holistic understanding of disability through the introduction of first-person perspectives of individuals with disabilities, and critiques of the portrayal of disability in cultural mediums. Teacher educators are also integrating history into curricula to demonstrate that ableism and exclusion have persisted over centuries, and their legacies are reflected in the labels and educational services that students identified with disabilities receive today. These and other pedagogical approaches promote understanding of disability as a complex sociocultural phenomenon and depart from narrow conceptualizations traditionally offered by pathological characterizations in special education. Together, these approaches reflect an interdisciplinarity that Linton (1998) suggested is most effective for enacting disability studies.

However, the use of DS-aligned pedagogies have illuminated tensions and yielded mixed results. Many teacher candidates retain their initial normative and medicalized understandings of disability (Hulgin et al., 2014) or resist the perceived politicized nature of advocating for inclusive education (Rice, 2006a). Further, disability studies remains largely isolated from other social justice oriented critical pedagogies that are commonly used in general education, and which do not yet acknowledge ableism as an oppressive ideology (Broderick & Lalvani, 2017). This divide remains despite, as Cochran-Smith and Dudley-Marling (2012) point out, “On its surface, the emphasis on greater access to the general curriculum is consistent with the perspectives of general teacher educators who work from a social justice stance” (p. 241). A DS perspective is likely to have a limited impact if it is relegated to only a course or two, rather than integrated across general education teacher education (Iannacci & Graham, 2013).

Perhaps the most pervasive challenge in the literature is the contradiction between perspectives within disability studies and what teacher candidates encounter in schools. Although teacher educators often speak of pedagogies that foster teacher agency, the “reality of reality” (Naraian & Schlessinger, 2017, p. 95) indicates that teacher candidates are likely to struggle and may forgo practices that enact DS perspectives when cultures and daily practices so strikingly conflict with disability studies theory. Dotger and Ashby’s (2010) study exposed just how quickly some teacher candidates abandon advocating for inclusive education when faced with a professional context, despite having completed several courses that are grounded in social justice and inclusive education perspectives. During a simulated meeting with an actor portraying a paraprofessional, several teachers quickly acquiesced to the paraprofessional’s suggestion to remove students with disabilities from taking part in instruction with their nondisabled peers. Approaches to teaching DS that ask teacher educators to teach “against the grain” (Danforth, 2014, p.7) of traditional school practices and become agents of change (Cosier & Pearson, 2016) may not be effective without also focusing on how to navigate the highly variable and seemingly incongruent professional contexts with which disability and inclusion are constructed and enacted (Naraian & Schlessinger, 2017).

It is a problem of progress that we have a better understanding of the tensions that emerge when teaching disability studies in teacher education – the result of wider implementation of deliberate and reflective pedagogy by teacher educators. From here, it will be important to continue to advance the fields of DS and teacher education by resolving some of the challenges documented by researchers. For example, future research should examine the strategic application of promising practices, such as the use of first-person narratives and teaching the history of disability. What other factors should we consider, and what adaptations can we make to better support teacher candidates’ meaningful engagement with social interpretations of disability, and reduce the likelihood that they will retain medicalized views (e.g., Hulgin et al., 2014)?

Further, it is important that teacher educators work collaboratively to introduce disability studies perspectives across teacher education. For example, the practice of assigning subject area teacher candidates to create K-12 lessons/units that address disability as a sociocultural phenomenon (Ferri, 2006) need not be relegated to a single course that addresses disability/special education. Beyond the humanities examples in this paper, content area methods classes in math and science would include topics such as eugenics and intelligence testing to highlight the connection between past attitudes about disability and concepts that teacher candidates will be required to teach. Disability studies should serve as an analytic framework introduced with other critical frameworks in foundations courses that ask teacher educators to examine how educational policies and practices preserve prevailing patterns of power, privilege, and hierarchy across racialized, gendered, and class lines (Bialka 2015; Loutzenheiser & Erevelles, 2019).

Disability studies should also be integrated into courses with curriculum that addresses the concepts of multicultural education and culturally responsive pedagogy. Teacher educators would be introduced to examples of disability culture including autistic identity (Sinclair, 2010), multicultural frameworks aimed at reducing deficit-based assumptions toward both disability and minoritized students (Kulkarni, 2019), and inclusive pedagogies that counter not just ableism but multiple forms of oppression (Waitoller & King Thorius, 2016). Such intersectional analysis could further be used to ask teacher candidates to consider the racialized and gendered construction of ability (Leonardo & Broderick, 2011) and how a lack of cultural responsiveness contributes to the disproportionate representation of minoritized students in special education. Finally, inclusive pedagogies promoted within DS should be integrated into general methods/theory courses that introduce teacher candidates to learning theories that are similarly aligned, such as social constructivism (Cochran-Smith & Dudley-Marling, 2012). Confining a UDL framework, for example, to disability/special education focused courses is counterintuitive, as UDL provides tools for all teacher candidates to deconstruct the existence of normative curriculum, and to develop flexible instructional approaches that accommodate the diverse needs of students from the onset (Wilson, 2017).

Beyond expanding the teaching of disability studies across teacher education, progress toward the ultimate goals of more inclusive schooling will require identifying pedagogies that can support novice teachers to work within the tensions between DS theory and medicalized approaches to disability in schools. Currently, approaches to teaching DS have not developed robust methods of effectively fostering the “practical (Gilham & Tompkins, 2016, p.17) that teacher candidates need to enact DS principles in the field. Further, there is increasing recognition that the notion of developing teacher candidates into agents of change who can transform their schooling contexts is unrealistic given the political and material realities of public schools (Naraian & Schlessinger, 2018). In order to work within the schools to incrementally advocate for and support inclusive practices, while maintaining a professional identity aligned with disability studies, Danforth and Naraian (2015) suggest that teachers need to develop a “situated agency” that is “always plural, shifting and contradictory” and may involve carrying out practices that appear on the surface to be inconsistent with the ideas of inclusive education and DS (p. 81). Similarly, Naraian and Schlessinger (2017) have argued that DS pedagogy should prepare teacher candidates by equipping them with the “cognitive resources” they need to pursue “possible trajectories of action they could take up that could have immediate consequences for the student” even if those actions do not always enact the ideals of disability studies (p. 96).

Efforts to better prepare teacher candidates to effectively enact disability studies within individual school contexts can be informed by the experiences of current teachers. Research by Broderick et al. (2012), Naraian and Schlessinger (2018), and Rood and Ashby (2018) provides insight into the obstacles faced by teachers who have graduated from DS-influenced teacher education programs, such as accountability policies that segregate students and the isolation that may result from challenging predominant practices in special education without the support of fellow teachers or administrators. Notably, Rood and Ashby (2018) found that eight of the eleven teachers in their study had planned to leave teaching, prompting them to ask “If teachers who believe in DSE are abandoning their respective teaching posts, what long-term impact can DSE have to unseat and challenge the oppressive systems of special education and public education?” (p. 14)

Disability studies informed teacher educators must continue to evolve in their approaches to preparing teacher candidates with the capacity to sustain themselves, and their inclusive pedagogies. For example, teaching collaborative skills must go beyond methods of co-teaching, to include how to build alliances with teachers and administrators who are unfamiliar with or apprehensive about DS perspectives (Broderick et al., 2012). Teacher educators should also work to establish communities of practice that include both teacher candidates and current teachers, which could function as a system to share resources and support the emotional labor of resisting medicalized and exclusionary responses to disability (Rood & Ashby, 2018). Teacher candidates would also benefit from opportunities to practice and reflect on difficult conversations with professionals who resist inclusive practices (Dotger & Ashby, 2010) as they will most likely encounter resistance from colleagues in schools.

In addition to these pedagogical approaches, it will be important to continue research that follows graduates of teacher education programs, in order that teacher educators can strategize about the ways we use texts, conduct activities, and develop assignments. Curriculum must be attuned to the reality of what is required to resist oppressive practices and provide meaningful educational access for all students. Teacher educators will also benefit from more research into enacting the ideals of DS within specific school structures and practices that teachers must navigate, such as Individual Education Plans (McLaughlin, 2016), response to intervention (Ferri, 2016), and assessment of disability (Bacon, 2016). Finally, there is a need for teacher educators to embrace the roots of disability studies activism by advocating for changes to policies, such as merging general and special education in state teaching certifications, which can support the elimination of a structural dis/ability binary and medicalized approaches to disability.

This literature review has several limitations. First, we recognize that in narrowing our inclusion criteria, we invariably excluded research that readers might assert is relevant to this paper’s focus on the intersection of disability studies and teacher education. We also did not include insights about introducing DS in interdisciplinary seminars (Baglieri & Ware, 2013) or within a doctorate degree program (Pearson, 2016), to name a few related areas that could be informative for teacher educators who are interested in introducing DS to teacher candidates. Our review also includes only academic research articles and book chapters, and does not account for the many pedagogical approaches that DS informed teachers are implementing and sharing through personal communication and social media. We also recognize that by excluding research done prior to 1999, we do not adequately account for the influence of pioneering pedagogical approaches in disability studies in education, “before it had a name” (Taylor, 2006). Finally, we did not include the many other scholars and teacher educators who teach and research with a commitment to inclusion, social justice, and “[t]he task of educating teachers for critical consciousness” (Ohito & Oyler, 2017, p. 189), but do not specifically identify with disability studies as a theoretical foundation.

Conclusion

Hulgin (2014) assert that, “anticipating student responses is essential in developing disability studies pedagogy” (para. 1). By reviewing pedagogical approaches, and the responses of teacher candidates to these approaches, this paper can support the further integration of disability studies into teacher education. To continue this evolution, it will be important to evaluate the sufficiency of sociocultural theories of disability and adapt methods of introducing disability studies to teacher candidates (e.g., Naraian & Schlessinger, 2017).

Achieving the transformational goals of DS will require teacher educators to develop pedagogies that provide teacher candidates with approaches to make incremental change, through ideological contradictions, while working within the system as is. Allying with teacher educators across disciplines can better disseminate the perspectives offered by disability studies and support teacher candidates’ critical and intersectional analysis of, and responses to, marginalizing practices in schools. Disruption of the medicalization of disability in schools, and cultivating and sustaining inclusive education, necessitates that teacher candidates be better prepared to navigate the professional context of resistance.

Footnotes

[1] The acronym “DS” is used to refer to the field of disability studies, though “disability studies” is occasionally written out to clarify for the reader.

[2] “Disability studies in education”, often referred to as “DSE,” is used to frame a line of research that is reviewed in this paper. However, “disability studies” is referred to more broadly throughout the paper, recognizing the interdisciplinary influence on pedagogical approaches of teacher educators who are informed by disability studies.

[3] Teacher education refers to instructional programs that prepare aspiring teachers, referred to as “teacher candidates,” for professional employment. Postsecondary faculty members who teach courses taken by teacher candidates are referred to as “teacher educators.” The research reviewed in this paper is primarily conducted by researchers in the United States, most of whom identify as both teacher educators and researchers within the field of disability studies.

References

Allan, J. (2006). Conversations across disability and difference: Teacher education seeking inclusion. In S. Danforth, & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 347–362). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, E. B. (2016). Inclusive education’s promises and trajectories: Critical notes about future research on a venerable idea. Education Policy Analysis Archives/Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 24, 1–29. doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.1919

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37(2), 89–99.

Bacon, J. K. (2016). Navigating assessment: Understanding students through a disability studies lens. In M. Cosier & C. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 39–60). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Bacon, J., & Blachman, S. (2017). A disability studies in education analysis of the edTPA through teacher candidate perspectives. Teacher Education and Special Education, 40(4), 278–286. doi.org/10.1177/0888406417730110

Baglieri, S., Bejoian, L. M., Broderick, A. A., Connor, D. J., & Valle, J.. [Re]Claiming “inclusive education” toward cohesion in educational reform: Disability studies unravels the myth of the normal child. Teachers College Record, 113(10), 2122–2154.

Baglieri, S., Valle, J. W., Connor, D. J., & Gallagher, D. J. (2011). Disability studies in education: The need for a plurality of perspectives on disability. Remedial and Special Education, 32(4), 267–278. doi.org/10.1177/0741932510362200

Baglieri, S., & Ware, L. (2013). Ending the longing for belonging. In A. Kanter & B. Ferri (Eds.) Righting educational wrongs: Disability studies in law and education (pp. 48–55). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Banks, J. A. (2016). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching.

Bialka, C. S. (2015). Deconstructing dispositions: Toward a critical ability theory in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 37(2), 138–155. doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2015.1004602

Bialka, C. S. (2017). Understanding the factors that shape dispositions toward students with disabilities: A case study of three general education pre-service teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(6), 616–636.

Blanton, L. P., Griffin, C. C., Winn, J. A., & Pugach, M. C. (1997). Teacher education in transition: Collaborative programs to prepare general and special educators. Denver, CO: Love Publishing.

Blanton, L. P., & Pugach, M. C. (2011). Using a classification system to probe the meaning of dual licensure in general and special education. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 34(3). doi.org/10.1177/0888406411404569

Blanton L. P., & Pugach, M. C. (2017). A dynamic model for the next generation of research on teacher education for inclusion. In L. Florian & N. Pantić (Eds.), Teacher education for the changing demographics of schooling: Inclusive learning and educational equity, vol. 2. New York, NY: Springer.

Brantlinger, E. (2006). The big glossies: How textbooks structure (special) education. In E. Brantlinger (Ed.), Who benefits from special education? (pp. 45–75). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Broderick, A. A., Hawkins, G., Henze, S., Mirasol-Spath, C., Pollack-Berkovits, R., Clune, H. P., & Steel, C. (2012). Teacher counternarratives: Transgressing and ‘restorying’ disability in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(8), 825–842. doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2010.526636

Broderick, A., & Lalvani, P. (2017). Dysconscious ableism: Toward a liberatory praxis in teacher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(9), 894–905.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Dudley-Marling, C. (2012). Diversity in teacher education and special education: The issues that divide. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(4), 237–244.

Connor, D. J., Gabel, S. L., Gallagher, D. J., & Morton, M. (2008). Disability studies and inclusive education—implications for theory, research, and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5-6), 441–457. doi.org/10.1080/13603110802377482

Connor, D. J., Valle, J. W., & Hale, C. (2012). Forum guest editors’ introduction: Disability studies in education “at work.” Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 8(3).

Cosier, M. (2016). Professional development in inclusive school reform: The need for critical and functional approaches. In M. Cosier & C. E. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 295–313). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Cosier, M., & Ashby, C. (2016). Disability studies and the “work” of educators. In M. Cosier & C. E. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 1–19). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Cosier, M., McKee, A., & Gomez, A. (2016). A study of the impact of disability studies on the perceptions of education professionals. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 12(4).

Cosier, M., & Pearson, H. (2016). Can we talk? The underdeveloped dialogue between teacher education and disability studies. SAGE Open, 6(1). doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244015626766

Crawford, F. A., & Bartolomé, L. I. (2010). Labeling and treating linguistic minority students with disabilities as deficient and outside the normal curve: A pedagogy of exclusion. In C. Dudley-Marling & A. Gurn (Eds.), The myth of the normal curve (pp. 151–170). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Danforth, S. (Ed.). (2014). Becoming a great inclusive educator. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Danforth, S., & Naraian, S. (2015). This new field of inclusive education: Beginning a dialogue on conceptual foundations. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 53(1), 70–85.

Derby, J. (2016). Confronting ableism: Disability studies pedagogy in preservice art education. Studies in Art Education, 57(2), 102-119.

Dotger, B., & Ashby, C. (2010). Exposing conditional inclusive ideologies through simulated interactions. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 33(2), 114–130. doi.org/10.1177/0888406409357541

Ferri, B. A. (2006). Teaching to trouble. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 289–306). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Ferri, B. (2016). Reimagining response to intervention (RTI) from a DSE perspective. In M. Cosier & C. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 153–166). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Freedman, J. E. (2016). An analysis of the discourses on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in US special education textbooks, with implications for inclusive education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(1), 32–51.

Gilham, C. M., & Tompkins, J. (2016). Inclusion reconceptualized: Pre-service teacher education and disability studies in education. Canadian Journal of Education, 39(4).

Heroux, J. R. (2017). Infusing disability studies within special education: A personal story. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 13(1).

Hulgin, K., O’Connor, S., Fitch, E. F., & Gutsell, M. (2014). Disability studies pedagogy: Engaging dissonance and meaning making. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 7(3 & 4).

Iannacci, L., & Graham, B. (2013). Reconceptualizing “Special Education” curriculum in a Bachelor of Education program: Teacher candidate discourses and teacher educator practices. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 2(2), 10–34.

IDEIA (2004). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, PL108-446, 20 U.S.C. §1400 et seq. [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pdf/pl108-446.pdf

Jones, M. M. (2011). Awakening teachers strategies for deconstructing disability and constructing ability. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5(4), 218–229.

King, J. E. (1991). Dysconscious racism: Ideology, identity, and the miseducation of teachers. The Journal of Negro Education, 60(2), 133–146.

Kulkarni, S. S. (2019). Towards a critical disability studies model of teacher education. In K. Ellis, R. Garland-Thomson, M. Kent, & R. Robertson (Eds.). Interdisciplinary approaches to disability: Looking towards the future (Vol. 2). Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge.

Kuranishi, A., & Oyler, C. (2017). I failed the edTPA. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 40(4), 299–313. doi.org/10.1177/0888406417730111

Lalvani, P., & Broderick, A. A. (2013). Institutionalized ableism and the misguided “Disability Awareness Day”: Transformative pedagogies for teacher education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 46(4), 468–483. doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2013.838484

Leonardo, Z., & Broderick, A. (2011). Smartness as property: A critical exploration of intersections between whiteness and disability studies. Teachers College Record, 113(10), 2206–2232.

Linton, S. (1998). Claiming disability: Knowledge and identity. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Loutzenheiser, L. W., & Erevelles, N. (2019). [Special issue] ‘What’s disability got to do with it?’: Crippin’ educational studies at the intersections. Educational Studies, 54(3), 1–12. doi/full/10.1080/00131946.2018.1463768

McLaughlin, K. (2016). Institutional constructions of disability as deficit: Rethinking the individualized education plan. In M. Cosier & C. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 83–102). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Mutua, K., & Smith, R. M. (2006). Disrupting normalcy and the practical concerns of classroom teachers. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 121–132). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Naraian, S., & Schlessinger, S. (2017). When theory meets the “reality of reality”: Reviewing the sufficiency of the social model of disability as a foundation for teacher preparation for inclusive education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(1), 81.

Naraian, S., & Schlessinger, S. (2018). Becoming an inclusive educator: Agentive maneuverings in collaboratively taught classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 179–189.

Ohito, E. O., & Oyler, C. (2017). Feeling our way toward inclusive counter-hegemonic pedagogies in teacher education. In L. Florian & N. Pantić (Eds.) Teacher education for the changing demographics of schooling (pp. 183-198). New York, NY: Springer.

Oyler, C. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive and critical (special) education. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 34(3), 201–218. doi.org/10.1177/0888406411406745

Pearson, H. (2016). The impact of disability studies curriculum on education professionals’ perspectives and practice: Implications for education, social justice, and social change. Disability Studies Quarterly, 36(2).

Pugach, M. (1988). Special education as a constraint on teacher education reform. Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 52–59. doi.org/10.1177/002248718803900310

Rice, N. (2006a). Promoting ‘Epistemic Fissures’: Disability studies in teacher education. Teaching Education, 17(3), 251–264.

Rice, N. (2006b). Teacher education as a site of resistance. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 17–32). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Rood, C. E., & Ashby, C. (2018). Losing hope for change: Socially just and disability studies in education educators’ choice to leave public schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–17. doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1452054

Sapon-Shevin, M. (2003). Inclusion: A matter of social justice. Educational Leadership, 61(2), 25–28.

Sinclair, J. (2010). Being autistic together. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(1).

Stephens, T. M. (1988). Eliminating special education: Is this the solution? Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 60-64. doi.org/10.1177/002248718803900311

Taylor, S. J. (2006). Before it had a name: Exploring the historical roots of disability studies in education. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 289–306). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Valle, J. (2016). Learning from and collaborating with families: The case for DSE in teacher education. In M. Cosier & C. Ashby (Eds.), Enacting change from within: Disability studies meets teaching and teacher education (pp. 243–264). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Van Hove, G., De Schauwer, E., Mortier, K., Claes, L., De Munck, K., Verstichele, M., Vandekinderen, C., Leyman, K., & Thienpondt, L. (2014). Supporting graduate students toward “a pedagogy of hope”: Resisting and redefining traditional notions of disability. Review of Disability Studies: An International Journal, 8(3).

Waitoller, F. R., & King Thorius, K. A. (2016). Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and universal design for learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 366–389.

Ware, L. (2005). Many possible futures, many different directions: Merging critical special education and disability studies. In S. L. Gabel (Ed.), Disability studies in education: Readings in theory and method, (pp. 103–124). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Ware, L. (2006a). A “look” at the way we look at disability. In S. Danforth & S. Gabel (Eds.), Vital questions facing disability studies in education (pp. 271–288). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Ware, L. (2006b). Urban educators, disability studies and education: Excavations in schools and society. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10(2-3), 149–168. doi.org/10.1080/13603110500256111

Wilson, J. D. (2017). Reimagining disability and inclusive education through universal design for learning. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37(2). Retrieved from http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5417/4650

Zola, I. K. (1976). Medicine as an institution of social control. Ekistics, 41(245), 210–214