Approaching Disability Studies in Physical Therapist Education: Tensions, Successes, and Future Directions

By Heather A. Feldner, PT, PhD, PCS1,2,3

Kathryn D. Lent, PT, PhD1

Stacia Lee, PT, NCS1

1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

2Disability Studies Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

3Center for Research and Education on Accessible Technology and Experiences (CREATE), University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Abstract

Historically, the field of disability studies has been critical of philosophical and pedagogical approaches within rehabilitation fields such as physical therapy, traditionally situated within a medical model of disability. While the emphasis within the profession of physical therapy has shifted toward participation and inclusion, how this is fundamentally carried out in day-to-day educational practices has remained rooted in pedagogic approaches that situate disability as an individual deficit to be remediated with therapeutic intervention, rather than acknowledging disability as a complex experience or aspect of identity largely impacted by disabling social and environmental structures and expectations of ‘normality.’ We argue that disability studies principles can and should be essential components of physical therapist education, to understand the lived experiences of disabled people, address traditional power dynamics within the healthcare system, become better allies to disabled people, and reframe/reimagine how professional education unfolds. We provide a background of the tensions between disability studies and professional physical therapist education; an outline of challenges to the integration of these discipline; and describe disability studies content within a professional physical therapist education program. We critically reflect on the positionality and background of the course instructors, methods of instruction, context within overall curriculum, student responses and feedback, and lessons learned. We also provide future directions for intersectional inquiry, including an example of how this content may expand into a dedicated course or course series integrating disability studies principles throughout curricular processes, providing inclusive and holistic education to the next generation of physical therapists.

Keywords: disability studies, pedagogy, health professions education, physical therapy, intersectional inquiry, curriculum

Historically, the field of disability studies has been critical of both philosophical and pedagogical approaches within rehabilitation fields such as physical therapy (PT), which have traditionally been situated within a medical model of disability (Abberley, 1995; Kielhofner, 2005; Linton, 1998; Roush & Sharby, 2011). Over the past decade, the philosophical emphasis within the PT profession has shifted more toward participation and inclusion (Roush & Sharby, 2011). However, focused attention on body/mind structures and functions of disabled people, and underlying assumptions and prejudices about disability and quality of life, remain prevalent in practice as well as professional education (Gibson, 2016; Kielhofner, 2005; Shakespeare et al., 2009). Further, pedagogical processes employed in teaching PT students have largely remained rooted in approaches that situate disability as an individual deficit to be remediated by therapeutic intervention, rather than acknowledging disability as a complex experience or aspect of identity[1]—one that is fundamentally impacted by disabling social and environmental structures and expectations of “normality” (Gibson, 2016; Linton, 1998; Shakespeare et al., 2009; Seelman, 2004; Yorke et al., 2017). Additionally, the financial and practical considerations of integrating disability studies content into a full, traditionally sequential doctoral-level PT (DPT) curriculum that is subject to the guidelines of professional licensure and educational accreditation regulations has been challenging.

Despite these challenges and historical tensions, however, we argue that disability studies principles can and should be essential components of PT education, to better understand the lived experiences of disabled people, address traditional power dynamics within the healthcare system, become better allies to disabled people with whom we encounter in professional roles, and reframe/reimagine how professional education unfolds.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide (a) A brief background of professional PT education and the tensions that exist between PT and disability studies; (b) An outline of barriers and facilitators to integrating these disciplines; and (c) A critical analysis of the introduction of disability studies content within the DPT program at the University of Washington. We critically reflect on the positionality and background of the course instructors, curricular context, pedagogical strategies, student responses, and lessons learned. We also provide future directions for intersectional inquiry, including a structured example of how this content may be expanded into a dedicated course or course series, and describe our vision of integrating disability studies principles throughout curricular processes to provide inclusive and holistic PT education.

Physical Therapist Profession and Education

The PT profession within the United States was born during the early to mid 1900’s, following the return home of disabled veterans from the World Wars and the growth of the population living with polio (Moffat, 2003). While professional roles and educational practices have evolved throughout the years, the current American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) vision statement notes that the goal of PT practice is “transforming society by optimizing movement to improve the human experience,” which both situates the focus of PT on movement, but more broadly appeals to physical therapists to consider their work as influential to participation in society at large (American Physical Therapy Association, 2019).

Professional PT education in the United States is a three-year doctoral degree program that combines intensive didactic training with clinical experiences across a variety of healthcare settings. According to the APTA,

Primary instructional content areas in the curriculum may include, but is not limited to biology/anatomy, cellular histology, physiology, exercise physiology, biomechanics, kinesiology, neuroscience, pharmacology, pathology, behavioral sciences, communication, ethics/values, management sciences, finance, sociology, clinical reasoning, evidence-based practice, cardiovascular and pulmonary, endocrine and metabolic, and musculoskeletal. (2019)

Once students have graduated from an accredited physical therapy program, they become eligible to sit for the national licensure examination, on which a passing score is required in order to practice physical therapy in a clinical or educational setting.

With this focus on body/mind structures and functions in physical therapist education, even with the more recent philosophical shift in the vision of the profession toward participation, it is not surprising that disability studies as a field of academic inquiry has been critical.

The current model for PT practice and education is the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization, 2002). The ICF framework is intended to guide healthcare professionals by considering health conditions related to their impact across domains of body structures/functions, activities, participation, environmental contextual factors, and personal contextual factors specific to the individual (World Health Organization, 2002). Similar to the shifting definitions of disability based on societal perception, the ICF framework is a model of health and disability that was created in response to models of disability that were largely focused on impairment (Goering, 2015). Thus, in PT practice greater emphasis on how intervention can impact activity and participation, and not just body structure and function, has resulted from adoption of the ICF. However, despite the attempted shift away from impairment, the ICF framework and the Medical Model of Disability both continue to perpetuate the notion that disability is located within the individual, whereas other models such as the Social Model of Disability, locate disability within the environment and society itself (Goering, 2015).

Tensions, Barriers, and Opportunities

While the fields of occupational therapy and social work have more proactively addressed this critique, examining how tensions may be recognized and used to fuel critical learning (Kielhofner, 2005; Gilson & DePoy, 2002; Magasi, 2008), little has been written addressing how disability studies can specifically inform PT education or practice. In fact, in some instances physical therapists have contributed further to this divide in their scholarly work. For example, in a perspectives piece within a high-impact PT journal on alternative models of disability and the paradox of PT practice, the authors note in their introductory as well as their conclusory sentence, “Physical therapists know disability” (Roush & Sharby, 2011, pp. 1716, 1724). They later state, “Our value to individuals and society is apparent, and we rightly enjoy our role in our clients’ success,” and note with surprise that much of the literature proposing reconceptualization of disability has been especially critical of rehabilitation professions (pp. 1716). While the remainder of the article attempts to reconcile the ways in which disability studies principles can inform practice, it refrains from endorsing any apparent value in doing so, thus rendering the approach inherently problematic from a disability studies perspective and affirming contemporary critiques of rehabilitation as a self-aggrandizing profession (Abberley, 1995; French & Swain, 2001; Gibson, 2016; Linton, 1998).

It is this very disconnect within rehabilitation that has been highlighted in seminal scholarship by Linton (1998) as a rationale for maintaining disability studies as a liberal arts-based exploration of the socio-political experiences of disabled people distinct from the domination of a medical/rehabilitation perspective. The harm of continuing educational practices that remain rooted in a medical model, however, is that this practice perpetuates the false empowerment of PT students, which manifests in clinical practice environments where professional expertise outweighs lived expertise and an ableist ‘helping’ mentality is perpetuated. This practice disregards disabled people as experts in their own lives, further negating the acknowledgment of these lived experiences within a society that systematically oppresses and marginalizes disabled people.

Institutional and practical barriers to including disability studies content in physical therapist education exist as well. First, physical therapists are practicing within a healthcare system that may, as Seelman (2004) writes, “Aid and abet the objectives of health care as a commodity, not a right” (para. 5), which leaves little room to explore disability from a humanities perspective in a business-driven model. Practically, the integration of disability studies into rehabilitation education has also been challenging due to a variety of factors, including the sequencing and demands of curricula bound by PT education accrediting bodies, fiscal considerations such as student debt and reluctance to prolong (and pay for) an extended program that includes more disability studies electives, student stress and mental health, and changing health care policy that emphasizes productivity over advocacy (Magasi, 2008; Seelman, 2004). Including disability studies in PT education may be a powerful solution to address this complex curricular and societal/attitudinal climate; however, inertia may remain. Seelman (2004) argued more than a decade ago, “The professional, clinical and policy incentive/disincentive mix is skewed to favor the status quo. It creates barriers to realizing the benefits of teaching and learning about the experience of people with disabilities” (para. 6). For students, a consequence of the status quo can be a lack of understanding of advocacy and disability justice as well as an inflated sense of expertise about disability. For disabled people, a consequence of this focus is often the suppression of their own voices, perceptions, and competencies in rehabilitation education (Oliver & Barnes, 2010; Shakespeare & Kleine, 2013).

Opportunities for Integrating Disability Studies Content

Despite these challenges, we believe efforts to infuse PT education with disability studies content have inherent value. As Gibson (2016) argues in her critical re-examination of rehabilitation from a disability studies lens, physical therapists can play an important role in their disabled clients’ ability to “live well” (p. 3). For example, disabled people may seek PT services for pain management strategies, supportive mobility equipment, exercise and wellness recommendations, or problem solving for improved access and participation in meaningful activities. Further, physical therapists have an important opportunity to use their relative position of privilege and power to advocate for greater health equity for disabled people. Discriminatory practices and systemic disadvantages in housing, employment, economic, judicial, educational, and social spheres interact to affect health and access to health care (Algood & Davis, 2019; Longmore, 2003). Thus, having a foundational understanding of the complex institutional phenomena that affect disabled people is essential to effectively provide equitable, person-centered PT care and advocate for the expansion of this care to combat inequity and ensure meaningful translation to community living and participation.

In these ways, physical therapists may be key allies for disabled people, if a rehabilitation relationship is created based on empowerment principles that elevate the lived experiences, self-defined needs, and expertise of disabled people on their own terms (Gibson, 2016; Shakespeare et al., 2009; Magasi, 2008). In fact, Magasi (2008) argues that the very tension pointed out by Linton and other disability studies scholars (and witnessed within Roush & Sharby, 2011) is also the very reason disability studies cannot be siloed, but instead infused in professional rehabilitation education as a response and opportunity to critically examine the status quo of rehabilitation education as an institutional practice—what Magasi denotes as, “a challenge that is at once obvious and transformative” (2008, p. 285).

As physical therapists with educational background in disability studies, and as educators in a professional PT program, we agree with the position of Magasi, Gibson, Seelman, and others. We look to our disabled colleagues and allies in disability studies to partner in pushing this change forward. We look to the contemporary example of our colleagues in Occupational Therapy (Kielhofner, 2005; Heffron et al., 2019) who, in both research and educational practices, have successfully begun navigating these tensions and exploring how disability studies content can enhance and, in fact, provide a pivotal perspective for future rehabilitation professionals. We are at the very beginning of this journey within PT education, and look forward to the challenges, opportunities, and learning experiences ahead.

Infusing Disability Studies Content: The Curricular Experience

The University of Washington DPT program is situated within the university’s School of Medicine and Department of Rehabilitation Medicine. There are 48 students per cohort in our three-year program, and we introduced disability studies content to the cohort in the summer of their second year, just prior to their departure for a series of three, full-time clinical internships that culminate in the completion of their degree. Because the curriculum does not currently have a dedicated course or thread of disability from a disability studies perspective, the content was delivered as a part of the Administrative Issues course.

The intent of the administration course is to educate the entry level doctoral students on the business aspect of running a PT practice. The course includes in-depth discussion and problem-solving activities related to physical therapists as managers within health care systems or private practices. Topics covered include economic trends, operational policy, budgeting, reimbursement, compliance with billing, human resource management including supervision of physical therapy assistants, interdisciplinary communication, disability equity, program development, business structure/models, telemedicine, and entrepreneurship.

While disability equity topics are touched on briefly during students’ first year, they are revisited in much greater depth during this course. Educating students about different disability models, disability equity, and their own personal biases is considered an essential component of this course from a policy and management perspective, as it factors into the majority of elements of the overall administration course as well as their future practice. However, there is ongoing discussion amongst faculty as to the optimal location or timing for delivering this content in the future.

Prior to the course session, students were asked to engage with materials that included a written brief on the history of the disability rights movement (Anti-Defamation League, 2020), a video describing Ableism (Social Justice Project, 2013), and a website article on intersectionality (Cooper, 2017). These were accessed from the course website, and discussion of the materials was embedded into session activities. We also asked the students to arrive to class scent free and provided introductory justification and resources for this request. Following the course session, each student was required to submit a reflection assignment based on the following prompts:

- Describe your reaction/response to the session and provide 1-2 main takeaways that you learned about disability equity and justice.

- Describe one practical action step that you can take as you embark on your clinicals that is related to disability studies content and relevant to your own goals as a student and future physical therapy professional.

Students had a choice of three submission formats via written reflection, audio response, or original artwork. Although a preferred due date was set and communicated to the students, an automatic one-week extension was granted, no questions asked, and students were encouraged to reach out individually if additional time beyond the extension was needed. We purposely offered these choices and extended deadlines to improve the accessibility of our assessment processes. Permission from the students was sought prior to sharing de-identified reflection responses, and our institutional review board granted exempt status approval for this paper.

| Session Outline | Learning Objectives |

|---|---|

| • Introduction and Accessibility Notes • Equality, Equity, and Liberation • Models of Disability • Intersectionality and Axes of Privilege • Disability History and the Disability Rights Movement • Ableism and Language Context for Physical Therapy • Practice—How are we addressing Disability Equity in our program and in our profession? | • Students will compare and contrast different models of disability • Students will explore their own axes of privilege and describe intersectionality in the context of disability justice • Students will critically examine how the Disability Rights Movement has influenced policy and social/ environmental/ educational barriers faced by disabled people • Students will evaluate how principles of disability studies and disability equity apply in the context of physical therapist practice |

Positionality of the Instructors and Accessibility Notes

We believed it was important to begin the session by acknowledging our own positionality and addressing the lack of representation by disabled faculty within our program. Although our instructor team includes members with marginalized intersecting identities in other dimensions (race and sexuality), none currently identify as disabled, but rather as family members of disabled people and allies to disability communities. This issue is systemic across institutions of higher education, including those institutions that engage in disability studies pedagogy (Brown & Leigh, 2018). We addressed this in a large group format, disclosing our own positionality and identity, and stating that both our preference and goal for future coursework is for the direct involvement of a disabled colleague in creating and delivering this content.

We also initiated a full series of accessibility notes, delivered within the large group introduction. This included a detailed self-description of each presenter, a description of the room, the location of the exits (including the emergency exit, which unfortunately opened to a stairwell), the location of the restrooms, the location of a quiet space, a request for consistent microphone use, and an invitation to knit, fidget, stim, or move about and position oneself however comfortable to maximize participation in the discussion. We addressed the multiple instructional and assessment formats associated with the session and offered large-print copies of our handouts. We also acknowledged where our accessibility efforts had fallen short, in that the session was not being recorded for later review, captioned, or interpreted in American Sign Language, and used this opportunity to discuss accessibility as an ongoing learning and action process.

This type of inclusive introduction is not routinely conducted in our program and many students were taken by surprise, reacting to this activity specifically in their reflections. Student A noted,

I was struck by how much we omit when ability is assumed from the visual environment to physical spaces, to the speed and amplification of our speech. In the typical classroom setting, it’s assumed that you can hear, mobilize around the environment, and take in all the information. Simply recognizing the assumption allows us to recognize bias and the likely value system that is attached to it. (2019)

Student B described that prior to the session she never would have thought of this type of access:

When Heather and Kathryn introduced themselves to the class and began describing themselves, the layout of the room, the entrances/exits/bathrooms, and offered different methods of interacting during the class (larger print of handouts), it instantly made me aware of possible disability inequity that I had never thought about before. What is difficult is that I would never have thought about these aspects if the idea had not been presented to me. And I know that the onus usually remains on the individual who is experiencing the inequity to open up the eyes of others which is a large burden to bear. (2019)

We also found our scent-free accessibility request to be met with curiosity, confusion, and even subtle pushback, even after providing a written justification and step-by-step instructions on how to accomplish the request. For example, Student C emailed prior to the session:

I was wondering if you could provide more of an explanation as to why you want us to arrive to REHAB 535 fragrance free. Is this part of our learning experience? Or is this a specific request from a faculty member or student? (2019)

Student D. (2019) reflected on the potential complexity of competing accessibility needs, stating, “There is a fine line for respecting the needs of everyone. As for example, scents can be stress relieving for some and stress inducing for others.” Accessibility requests and introductory notes were a simple tool to begin the session, but created an opportunity to provide novel information, elicit deeper thinking, and, at times, profound insights from the students. We believe that this could be an efficient but powerful means of engagement at the beginning of each course in the physical therapy curriculum, to both ‘standardize’ inclusivity as well as challenge the ableist assumptions of a graduate learning environment focused largely on the body and its normative (or departure from normative) function.

Equity and Models of Disability

In keeping with the title and focus of the session, defining and emphasizing equity in the context of disability was tremendously important as a foundation for building subsequent content. We used a widely available public visual image [www.storybasedstrategy.org/tools-and-resources], depicting sports spectators of different statures standing on crates, demonstrating how distribution of the crates or removal of barriers affects access through the lenses of equality, equity, and liberation. This was presented with acknowledgement that discussions about equality, equity, and diversity are becoming increasingly part of everyday professional life as a PT. We facilitated a large group discussion, prompting students to think about how they might describe the image to someone with a visual impairment, describe the differences between equality and equity, and consider why including a representation of liberation is important to our role in the PT profession. In an attempt to directly apply these concepts to disability studies, we asked students to consider what progress has or has not occurred in achieving equity for disabled people in the areas of education, employment, or public access.

Using equity as a foundation, we then introduced various models of disability to expose students to models that differ from the familiar ICF. This was done to provide students with a brief overview of the core beliefs related to each model, the context of disability within the goals of each model, and the relational aspects of disability as they pertain to identity, society, the environment, or culture, as appropriate. Students were introduced to medical, social, minority, and political-relational models of disability to assist in recognizing that students’ own identity, experiences, biases, and how they conceptualize disability, whether consciously or subconsciously, will affect every aspect of their future role as physical therapists.

For some students, the discussion provided the opportunity for novel perspectives. As Student E noted,

I enjoyed our conversation about how disability is a social construct. I had to think about it for a while, but I came to realize that the barriers create the “disability,” not the other way around. In other words, if there were no systemic or environmental barriers to participation there would be no disability! That was a new way of looking at it for me. (2019)

Student F described,

Disability is not simply isolated to within people, but it exists as a changing model in the world we interact with every day…Rather than thinking of disability as an impairment, it is important to celebrate it as a part of human diversity… to consider disability from multiple facets such as body/mind, environment, and policy. It is important as a cohort to create a culture that seeks to change society from our own interactions with the world in order to promote removing barriers to participation for people with disability. (2019)

The pairing of these reflections highlights the various ways that students used the content to further their own understanding of disability studies. Student E demonstrated the importance of initial awareness, while Student F reflected on the material in a way that calls out both personal and collective responsibility to go beyond awareness and create equitable change in the world.

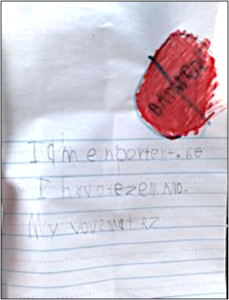

Several students provided reflections rooted in lived experience. For example, in Figure 1, the student described, “I’m submitting with this paper a picture of a piece of work that my six-year-old (then 5-year-old) made in kindergarten. It reads: “I am important because I have autism and my voice matters.” In the red circle with the X through it reads “bad words.” At age 5, he understood that bullying is never okay. He also understood that his voice, the voice of a child with autism, with a disability—a disability people fear more than deadly diseases such as measles, mumps, and reubella [sic] —his voice matters. It matters because he is human, just like everyone else. (Student G, 2019).

Figure 1

A child’s agency demonstrates abstract concepts of equity, identity, and societal perceptions.

Note. A piece of lined notebook paper with a red circle with an X through the words “bad words,” and a child’s writing underneath that says, “I am important because I have autism and my voice matters.”

(Artwork submitted by Student G)(Reprinted with permission).

This powerful reflection of a child’s agency demonstrates how abstract concepts of equity, identity, and societal perceptions bear real-world implications for disabled people throughout the lifespan. The resources at [www.storybasedstrategy.com] provide a host of tools that appear useful in engaging students in PT education to think more deeply about these concepts.

Intersectionality and Axes of Privilege

To provide a more individualized context to our discussion of disability and equity we chose to engage the students in a personal exercise examining their conceptualizations of identity, and how disability and other intersectional constructs may or may not contribute to relative privilege. We felt this was important for students to address in the context of their future role as healthcare providers in a relative position of power and privilege within a healthcare system rooted in the medical model of disability. Defining intersectionality based on Crenshaw’s (1989) seminal work and using Diller et al.’s (2018) Intersecting Axes of Privilege, Domination, and Oppression graphic, we requested that students individually locate where they fell on a continuum considering gender, race, disability, age, education, sexuality, and a host of other constructs of identity. Due to the potentially sensitive nature of this activity and identity disclosure, the students completed their Axes confidentially during a breakout session, and a large group discussion followed.

Students had varied responses to completing this exercise, and many reflected on their prior lack of knowledge. A white, male student stated, “I am apparently privileged, and I didn’t have any idea. Prior to this class I wouldn’t have considered myself privileged” (Student H); and another specifically addressed disability identity, noting, “One of the takeaways that I took from this lecture is how ignorant I have been about this. As an able-bodied individual, I have failed to realize the many privileges that I have in my community” (Student I). Our broader discussion elicited responses acknowledging that identity was complex, and disability was one piece of a complicated, intersectional construct. For example, another student, Student J, reflected, “Performing our own self-reflection on our axis of privilege helped to remind me of the many layers of intersectionality that blend into our identity, with disability being just one aspect of our identity” (2019).

Interestingly, students of color reflected less about disability and more about intersectional identity, culture, and society on a broader scale. Student K connected the exercise to an explicit need for more diversity within healthcare, stating,

It was interesting to have an explicit conversation about intersectionality. This cohort has lots in common—for example, many of us have a high degree of education and are relatively able-bodied—but one thing that has stood out to me in this program and the field of PT in general the disproportionate representation of people of color. One very salient experience to me, growing up in a very white suburb, is not being able to recall a medical practitioner who looked like me…It’s important to see representation of all types of people in this field. (2019)

Student L reflected on how aspects of their identity that were not privileged were, from their perspective, their greatest sources of pride, noting,

When I filled out my own axis, not only did I appreciate the ways in which I was privileged, I saw the areas in which I was not… Some ways in which I was “privileged” (e.g., fertility, age, socioeconomic status, education) aren’t as important to me as other aspects of my identity… My race and gender [are] the strongest drivers of my cultural identity. I have found immense strength and pride growing up as a black woman. (2019)

Given the complexity of identity and intersectionality, and the myriad ways that disability may be conceptualized as a part of identity, our goal was to create an introductory platform for our students that would both serve as a more immediate source of new knowledge, and an opportunity for longer term self-reflection. Using the Axes of Privilege, Domination, and Oppression appears to be a powerful pedagogic strategy to engage students in ways that are not being captured in other aspects of physical therapist education and is intimately connected to disability equity and the provision of healthcare services in a diverse community.

Disability History, the DRM, and Advocacy Today

How people come to know disability history and what they do in response varies based on sources of information, access to resources, prior knowledge and assumptions, the learning environment itself, cultural background, time available for learning, current relevance of the topic, and values associated with the content (Atherton & Steels, 2016). Disability history, and the rise of the Disability Rights Movement, however, are often neglected in health professions education (Fleischer & Zames, 2012; Atherton & Steels, 2012). We aimed to provide content in this area via two contrasting videos followed by small group discussion. The first video, a comedic interpretation chronicling the events and people surrounding the passage of Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, incorporated disabled actors portraying disabled activists and politicians (Comedy Central, 2018). The second was a documentary tracing the impact of political activism by disabled people and their allies that resulted in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 (Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, 2015).

Several students reflected on this content. One, Student M, focused on policy and attitude change, noting,

When our group discussed ADA’s successes and shortcomings, our discussions highlighted that the law can only go so far. However, the benefits of inclusion broaden people’s exposure to the unknown and helps change minds. The real battle is changing societal views on an issue and people in general. (2019)

The student identified a gap in the political approach that can be addressed through advocacy from an interactional perspective. Student N commented,

I was surprised that I hadn’t previously learned about the disability movement or Judy Heumann, however I think it was very eye opening, and it helped me really question what my role is in being an ally for people with disabilities, or people who are underserved or generally stigmatized. (2019)

These comments highlight how exposure to disability history, or lack thereof, can influence how students consume and respond to new information. Especially considering that the context of disability history is enmeshed in oppression and excluded, unintentionally and intentionally, through systems maintained by the majority, further exposure to this content is imperative to challenge the status quo, in PT education and beyond. These types of media are brief, approachable for students through humor and accurate representation, and can easily be incorporated across the PT curriculum for student consumption.

Ableism and Language

Language is powerful. In physical therapist education, this is no more evident than during a cohort’s first-year coursework, when person-first language (i.e., “person with a disability”), is engrained and mandated as the convention of our profession, so much so that departures from person-first language are often vilified by students and faculty alike. It is rare that acknowledgement of other naming conventions or concepts of re-claiming language occurs throughout our curriculum, yet this is an important discussion for healthcare professionals (Dunn & Andrews, 2015). Further, in a program which focuses on the physical body, an undercurrent of “benevolent ableism” tends to dominate, despite the best efforts of faculty members to present more holistic or value-neutral views of disability and illness (Nario-Redmond et al., 2019). For these reasons, we engaged our students in think-pair-share activities and small-group discussions to define ableism for themselves, identify examples of ableism in their everyday life, and consider their colloquial use of ableist language and how that language has historically impact disability communities. We then engaged in a large group discussion about person first versus. identity first language, and briefly introduced the idea of reclaiming.

The students identified examples of ableism they see around campus, which included the blockage of ramps with community-shared bikes, as well as in the classroom, with a lack of consistent microphone use, and provided examples of ableist language, including phrases such as “I’m so OCD” or “That’s so lame/crazy.” Only a handful of students reflected on ableism and language, however, and these responses varied. For example, Student O discussed her emerging awareness of ableism, noting,

I have never thought about some of the other words we utilize that can also be hurtful such as “lame” and “crazy”. I also have been thinking more about “person-first” and “identity-first” language and the use of the term “disability.” I hope to be more aware about the language that I use and become more confident with asking patients what language they would prefer. (2019)

However, another student, Student C, disagreed, stating,

This may be due to a lack of understanding, or due to my privilege as an abled body [sic] person, but I disagree with some of the examples of micro-aggressive language… I totally understand how calling someone crazy is offensive to people who have or who know individuals with mental illness. However, I think that efforts should be directed towards [sic] dissociating the word crazy with mental illness as opposed to discontinuing the use of the word. (2019)

Interestingly, several students discussed their discomfort with the word disability itself but made the reclaiming connection in their own way. One of them, Student P, reflected:

What about the word “disability” itself? It literally means that the person is limited in their senses, movements, or activities. It has a somewhat negative connotation, no? Is there a push among disability rights activists to change the label? Or are some people re-appropriating it as a source of pride? I suppose the nuances are similar to that of any civil rights movement. Might be an interesting discussion to have in class. (2019)

While we were surprised by some of these responses, we were also encouraged by the cascade of questions that arose from this discussion. We also acknowledged that we needed to meet students where they were in terms of thinking about disability; responses like those of Student K, above, demonstrate the need to be open to the tensions that surround these topics as we further integrate these principles into PT education. From a pedagogical standpoint, we struggled with how to best present and discuss ableism and language, as we hoped to avoid “lecturing” the students on what language they should or should not use, especially given our relative power and privilege as instructors. We believe infusing our training program with a greater focus on language and ableism is valuable and necessary; and will ultimately elevate the students’ future practice as physical therapists. However, methods of presentation will need to evolve and be refined as our curriculum develops.

Disability Equity in the Context of PT Practice

It was important that we avoid, as much as possible, talking about disabled people as patients, as this rhetoric is conventional in medical fields and perpetuates reductive or over-pathologized conceptions of disability (Shildrick, 2005). At the onset of the session, we intentionally introduced transdisciplinary content related to disability studies prior to explicitly returning to the practice of PT as it relates to disability. Thus, while PT was inherently embedded into conversation throughout, it was revisited in this final section of our session. We reflected back on the ICF and discussed how disability studies can be integrated into this familiar model as part of the environmental and personal factors that influence our approach to working with disabled people. Students were also encouraged to think about how principles of disability studies could be applied in clinical and academic settings across the PT profession.

Reflecting on these domains of PT, students shared their ideas for actionable next steps. One person, Student Q, shared an intent to respond differently, noting,

I will be more vocal when I hear tragic, sympathetic views toward people with disabilities. I will remind friends and family who hold these views that people with disabilities have lives as full, complex, challenging, joyful, heartbreaking, etc. as anyone else, and to view them as anything less is just false and detrimental to people with disabilities. (2019)

Another, Student R, took a proactive approach to advocacy opportunities, stating,

My [relative] is the director of a disability rights organization in [city]. After graduation, I’ll be moving down to [city] and I’m hoping that I can get involved in the organization and be a voice for accessibility and healthcare within the disability community. (2019)

Another, Student S (2019), identified a practical way to demonstrate inclusivity from a broader perspective, noting, “This class session motivated me to finally pull out the ‘she/her’ pin that I had ordered and to find a place for it on my backpack. I am now broadcasting to the world that pronouns are important to me.”

One student, Student T, made a critical recommendation for action for our academic program, stating,

As an educational rehab facility, I think it’s something that really should be in the forefront of our conversations and not just in special lectures like this, but throughout the work that we do… there could be a way for the program to infuse consideration of a wider range of people throughout the program, starting first quarter and going all the way through this last quarter that we’re in now. (2019)

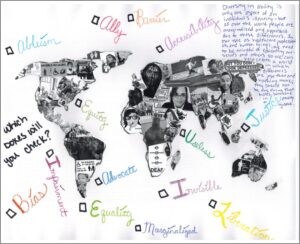

Another student, Student U, drew upon observations from a global perspective and submitted artwork (see Figure 2) for the reflection, narrating,

Diversity in ability is only one aspect of an individual’s identity—but all over the world people are marginalized and oppressed due to these differences. In our role as healthcare professionals and human beings, we need to be mindful of educating ourselves and others so we can help create a world where differences are just that and nothing more; they should not be the thing that holds someone in poverty and injustice. (2019)

Each of these responses connected current observations and understanding of disability to ways that we can and should advocate for more equitable approaches to disability as health care providers, personally and collectively.

Figure 2

Black and white disability related images and words as observations from a global perspective.

Note. Black and white disability related images and words cut out and arranged in the shape of the continents of the world. A caption that says, ‘Which boxes will you check?’ and words such as ‘Bias’, ‘Ally’, ‘Ableism’, and ‘Liberation’ surround the images. (Reprinted with permission).

Limitations and Future Directions

The disability studies content we delivered in our curricular experience was, aside from a few outlying perspectives, overwhelmingly well received by both students and faculty in our session. However, significant limitations exist. First, none of the presenters identified as disabled. Second, the content was delivered in a single course session, rather than a series, which compressed the time allotted to introduce and discuss complex disability issues. Third, the reflections submitted by the students were a required part of the coursework for credit, which could have created an affirmation bias among the responses. Fourth, although we attempted to address multiple ways of being in the world, intellectual disability received little attention. To address these limitations, we must continue refining our pedagogical methods, incorporate disability studies across a broader section of our curriculum, and routinely and intentionally include disabled people in the delivery of our curriculum.

We propose that disability studies content can be delivered across a structured, three-course series within the first two years of didactic PT education. For example, we envision a required introductory, two-credit, Disability Studies for Health Professionals seminar in year one of the curriculum. This could be an interdisciplinary opportunity for students in physical therapy, occupational therapy, prosthetics and orthotics, and speech and hearing sciences to introduce disability studies scholarship, disability history, and expand upon the topic foundations created during our initial pedagogical experience. Following this course, in the second year of the curriculum, we propose a required intermediate, one-credit Lived Experiences of Disability seminar, which foregrounds the expertise of disabled people, including experiences with rehabilitation professionals and other healthcare encounters, in addition to their perspectives of accessibility and body/mind diversity. This course would incorporate first-person narratives, speaker panels, autobiographical work, disability arts and culture, and blogs as well as qualitative research on consumer experiences of disabled people in healthcare settings. Third, as a capstone experience during the summer of the second year, just prior to departure on clinical experiences, we propose a one-credit elective on disability policy and advocacy for students interested in learning more about the ADA, World Health Organization conventions, and understanding how disability advocacy organizations support and empower disabled people in our community. This elective could be connected to existing service-learning opportunities with disability organizations serving the Seattle region. One significant limitation of developing these courses is finding time in already packed student schedules. By proposing a hybrid of required and elective coursework, it is our hope that these initiatives could be more easily embedded in the DPT curriculum. Finally, we propose the introduction of an annual faculty training series, similar in content and delivery to our initial endeavor described in this paper, to ensure all faculty in our program have a basic understanding of the disability studies perspective, why it is important for our profession, and how it can be leveraged to elevate our PT curriculum and our pedagogic engagement with students.

Ideally these courses would be co-instructed by disabled colleagues, but, at the very least, disabled community members would be paid for their time and expertise as co-developers of course design and content. We would capitalize on the precedence for this type of paid-expert involvement in current curricular offerings within our program, with a shifted focus toward disability empowerment and equity rather than biomedically based investigation and intervention. The PT Division and School of Medicine leadership are extremely supportive of this bridge work in disability studies and have expressed interest in expanding learning and training opportunities in the above ways.

Conclusion

We have presented our curricular experiences with infusing disability studies principles into PT education within an isolated course experience. However, in order to create a more holistic and equitable healthcare experience for disabled people, we believe, like Gibson, Magasi, Seelman, and other contemporaries, that disability studies must become an essential part of an integrated curriculum for students in entry-level PT education programs. It is important that students who will engage with disabled people throughout their careers are provided with opportunities to deepen their understanding of what disability means beyond medical management (Yorke et al., 2017). For these future health care providers, increased awareness of how health is affected by social determinants, including the role of environments, systems, organizations, and bias, is a necessity (Maldonado et al., 2014). However, deepening understanding of social determinants of health, disability models, and contextual factors associated with disability requires opportunities for increased engagement with disability studies to a greater extent than is currently undertaken (Kielhofner, 2005). We emphatically underscore the need for a concurrent intersectional approach toward incorporating disability studies content into DPT education, as we see this as an optimal strategy for providing equitable care that extends to clinical, educational, and research areas of practice, based on the needs and priorities for access and participation that disabled people identify as experts in their own lives.

1 We acknowledge that language is powerful, and, within the field of physical therapy, it is a convention to use person-first language, such as ‘person with a disability’ to denote the importance of the person rather than their disability. However, within the field of disability studies, many people prefer identity-first language, such as ‘disabled person,’ to denote that disability is a socio-political construct imposed upon people with impairments. Given the disability studies focus of this journal, as well as our desire to challenge the status quo of contemporary physical therapist education, we have consciously chosen to use identity-first language in this paper.

References

Abberley, P. (1995). Disabling ideology in health and welfare – the case of occupational therapy. Disability & Society, 10(2), 221-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599550023660

Algood, C., & Davis, A. M. (2019). Inequities in family quality of life for African-American families raising children with disabilities. Social Work in Public Health, 34(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1562399

American Physical Therapy Association. (2019, September 25). Vision statement for the physical therapy profession, HOD P06-13-18-22. https://www.apta.org/Vision/

Anti-Defamation League [ADL]. (2020). A brief history of the disability rights movement. http://www.adl.org/education/resources/backgrounders/disability-rights-movement

Atherton, H., & Steels, S. (2015). A hidden history: A survey of the teaching of eugenics in health, social care and pedagogical education and training courses in Europe. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 20(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629515619253

Brown, N., & Leigh, J. (2018). Ableism in academia: Where are the disabled and ill academics? Disability & Society, 33(6), 985–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1455627

Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (2015, June 30). The Americans with Disabilities Act, Signing Ceremony, July 26, 1990. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dFKicqqVME8&feature=youtu.be

Comedy Central. (2018, February 20). Drunk history season 5 Ep 5: Judy Heumann fights for people with disabilities. http://www.cc.com/video-clips/2p86bg/drunk-history-judy-heumann-fights-for-people-with-disabilities

Cooper, Y. (2017, June 01) Intersectionality. NCDA (National Career Development Association), 2020. https://www.ncda.org/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/139052/_PARENT/CC_layout_details/false

Crenshaw, K. (2018). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics [1989]. Feminist Legal Theory, 57–80. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429500480/chapters/10.4324/9780429500480-5

Diller, A., Houston, B., Morgan, K. P., & Ayim, M. (2018). The gender question in education: Theory, pedagogy, and politics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429496530

Dunn, D. S., & Andrews, E. E. (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70(3), 255–264. doi:10.1037/a0038636

Fleischer, D. Z., & Zames, F. (2012). The disability rights movement: From charity to confrontation [updated edition]. Temple University Press.

French S., & Swain, J. (2001). The relationship between disabled people and health and welfare professionals. In K. D. Albrecht, M. Seelman, & M. Bury (Eds.), Handbook of disability studies. Sage Publications (pp. 734–753). http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412976251.n33

Gibson, B. (2016). Rehabilitation: A post-critical approach. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19085

Gilson, S. F., & DePoy, E. (2002). Theoretical approaches to disability content in social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 38(1), 153-165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2002.10779088

Goering, S. (2015). Rethinking disability: The social model of disability and chronic disease. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 8(2), 134-138. DOI: 10.1007/s12178-015-9273-z

Heffron, J., Lee, D., VanPuymbrouck, L., Sheth, A. J., & Kish, J. (2019). The bigger picture: Occupational therapy practitioners’ perspectives on disability studies. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(2). https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.030163

Kielhofner, G. (2005). Rethinking disability and what to do about it: Disability studies and its implications for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59(5), 487-496. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.59.5.487

Linton, S. (1998). Disability studies/not disability studies. Disability & Society, 13(4), 525-539. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599826588

Longmore, P. K. (2003). Why I burned my book and other essays on disability. Temple University Press.

Magasi, S. (2008). Infusing disability studies into the rehabilitation sciences. Topics in stroke rehabilitation, 15(3), 283-287. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr1503-283

Maldonado, M. E., Fried, E. D., DuBose, T. D., Nelson, C., & Breida, M. (2014). The role that graduate medical education must play in ensuring health equity and eliminating health care disparities. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 11(4), 603-607. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201402-068PS

Moffat, M. (2003). The history of physical therapy practice in the United States. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 17(3), 15-25.

Nario‐Redmond, M. R., Kemerling, A. A., & Silverman, A. (2019). Hostile, benevolent, and ambivalent ableism: Contemporary manifestations. Journal of Social Issues, 75(3), 726-756. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12337

Oliver, M., & Barnes, C. (2010). Disability studies, disabled people and the struggle for inclusion. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(5), 547-560. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2010.500088

Roush, S. E., & Sharby, N. (2011). Disability reconsidered: The paradox of physical therapy. Physical Therapy, 91(12), 1715-1727. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100389

Seelman, K. D. (2004). Disability studies in education of public health and health professionals: Can it work for all involved? Disability Studies Quarterly, 24(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v24i4.888

Shakespeare, T., Iezzoni, L. I., & Groce, N. E. (2009). Disability and the training of health professionals. The Lancet, 374(9704), 1815-1816. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62050-X

Shakespeare, T., & Kleine, I. (2013). Educating health professionals about disability: A review of interventions. Health and Social Care Education, 2(2), 20-37. https://doi.org/10.11120/hsce.2013.00026

Shildrick, M. (2005). The disabled body, genealogy and undecidability. Cultural Studies, 19(6), 755-770. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380500365754

Social Justice Project. (2013, February 6). Ableism. Americans with disabilities act [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7_cMziG1Fc&feature=youtu.be

World Health Organization. (2002). Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

Yorke, A. M., Ruediger, T., & Voltenburg, N. (2017). Doctor of physical therapy students’ attitudes towards people with disabilities: A descriptive study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 39(1), 91-97. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2016.114083