“Look Down Your Shirt and Spell Attic”: Disability Encounters in El Deafo

T. K. Dalton

Adjunct Assistant Professor, English, City College of New York.

Abstract

Language, rhetoric, discourse, and voice are critical to Cece Bell’s El Deafo (2014), an autobiographical graphic novel detailing d/Deaf experience and aimed at a middle-grade audience, ages 7-12. The novel’s plot follows the character Cece Bell, starting when meningitis deafens her at age four. When taught alongside supporting American Sign Language (ASL) texts in translation from contemporary American Deaf Culture, El Deafo offers an opportunity to expose readers and writers to a variety of experiences of d/Deafness and disability. As a comic, El Deafo’s form strongly influences the interplay between friendship and disability. The visual presentation of the “A-T-T-I-C” page illustration underscores Cece’s affiliation with Martha, while also making important points about language, rhetoric and discourse, and the way the comics genre presents and complicates the burgeoning “voice” of its deaf narrator. The structure of the joke helps students access a text-based analysis: What is the joke? Who is telling it? To whom? Why?

This essay includes discussion of first-year writers (a) finding the narrator in Cece Bell’s El Deafo. In expository writing courses, careful positioning of the narrating voice finds itself—even to a skeptic of its utility in the composition classroom; (b) discussion of whether disability is “a good difference”; (c) considering El Deafo and “the material dimensions of composing” expository essays on disability; (d) working with “See what I’m saying” in visual presentations of shared discourse about multimodal texts; (e) using “Save me!” from “becoming hearing”; and (f) learning about textual reviewing, re-purposing, and reframing.

Keywords; graphic novel; vision; narrator

Pedagogically speaking, I am rarely happier than when my first-year writers mimic the habits of the advanced creative writing students who, 13 years ago, were my first audience as a college instructor. As a Graduate Teaching Fellow working in the University of Oregon’s Kidd Creative Writing Workshops, I conscientiously harped on the importance of precise use of language, of appropriate distance between narrator and subject, of dialectical reading, and of the development of authentic, nuanced, and clearly positioned points of view. These were the concerns—of language, of rhetoric, of discourse, and of voice—that occupied me when transitioning from the profession of journalism to the guild of fiction. Years later, these concerns of language, rhetoric, discourse, and voice are the ones that keep fresh the work of teaching composition to first-year writers. They are equally the concerns that help students improve the invention and execution of their own ideas and analysis. In this essay, I discuss one topic and text that worked particularly well to achieve these ends across two different student populations. The topic is the d/Deaf experience, and the text is Cece Bell’s autobiographical, middle-grade graphic novel El Deafo.

Where is the Narrator?

In the college courses in composition, creative writing, journalism, and literature I have taught since 2005, I often draw on my work as an interpreter and my upbringing in a “special needs” family with three disabled members: my deaf father, my autistic brother, and myself. Almost unavoidably, I incorporate into my teaching a critical analysis of American culture’s problematic public narrative about disability, deafness, and access. This is not unique to me (Browning, 2014; Brueggemann, Cheu, Dunn, Heifferon, & White or is it: Brueggemann, White, Dunn, Heifferon, & Cheu (2001); Dunn, 2010; Gould, 2008; Kennedy & Menten, 2010; Price, 2011; Stewart, 2010), but I attempt to model for my students the way my own mix of first-hand and second-hand knowledge shapes the questions I pose. The most interesting questions are the riskiest ones, the ones trained on experiences I cannot directly speak for—in this case, because I’m hearing, as are the students I discuss in this essay. The authenticity of any of our questions, then, is directly proportional to the clarity of the questioner’s own positioning. El Deafo, taught alongside a variety of supporting American Sign Language (ASL) texts in translation from contemporary American Deaf Culture (See Appendix A), offers a productive opportunity to position readers and writers in relation to experiences of d/Deafness and disability.

As defined by law (United States Census Bureau, 2018), disability is “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities,” and a disabled person is “a person who has a history or record of such an impairment, or a person who is perceived by others as having such an impairment.” This language comes from the original Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990; these definitions were retained and expanded under the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA) of 2008. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2018), 40.7 million Americans have a disability. Disability is a widespread experience across settings and institutions, and college is no exception. The most recent available federal Department of Education statistics report that 11.1 percent of college students have a documented disability. The actual number may be higher, but in composition classes, statistically, at least one or as many as three students in a given semester would benefit from accommodations. I had accommodations myself in high school and again in graduate school, though not as an undergraduate, a productive inconsistency discussed at the end of this essay. Put simply, as a disabled writer whose fiction and nonfiction often reflect on my own 15-year dance with epilepsy and pediatric brain tumors—overshadowed in my “special needs” family by my younger brother’s autism diagnosis and my father’s profound late-deafness, which occurred in his 30s—the inclusion of disability studies and disability literature in my writing classrooms is practically inevitable.

Since this essay is concerned with the writing classroom, its analytical center is a discussion of direct quotes from student writing. These come from an authentic range of student writing rather than renderings from memory of verbal class discussions. In my first-year writing classroom, such discussions are student-centered, pre-writing activities designed to build a set of meaningful questions aimed at a clearly defined audience of real people (i.e., themselves). The writing examined herein is included for the purpose of assessing the effectiveness of El Deafo and concepts from disability studies as a means of achieving this objective. This student writing emerged from these discussions, which themselves varied widely in length, group size, and formality. My description of my student-writers’ overall understanding of themes in Bell about friendship, childhood, school, and other topics also emerges from a synthesis of these discussions. I hope that this description of the audience the discourse community created is useful for instructors working outside of first-year writing. I also hope that readers who are not teaching aspects of writing in their course can easily adjust these findings to fit the dynamics of a course that relies more heavily on discussion or another discipline. (Or, conversely, that they might find a way to incorporate writing into their course.) In short, this work happened in first-year writing courses, and consequently, the most compelling evidence of student progress is student writing.

In expository writing courses, careful positioning of the narrating voice finds itself—even to a skeptic of its utility in the composition classroom—“at the nexus of our most fundamental and overlapping concerns as teachers and theorists” (Bowden, 1995, pp. 173-174). Guiding students through the process of using critical thinking to establish a rhetorical position is particularly useful in classrooms where teachers emphasize even traditional pedagogical tools like the lecture format to be “a problem-posing illumination which criticizes itself and challenges students’ thinking” (Freire and Shor, p. 40); to be clear, I include my own classrooms in that number. In these environments, practices like consensus-building, procedures adapted from responsive classroom philosophy, and the centering of “reflection as a means of alliance making” (Hsu, 2018, p. 149) all build the foundation for the effective inclusion of readings from disability literature. Disability literature is defined here as any creative work composed by a person who publicly identifies as disabled, as I do in my own classroom, typically on the first day while reading syllabus language about accommodations; disability studies is theoretical or scholarly work, including by nonacademic community thinkers (i.e., Ryan Commerson (2018) or Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018) that critiques aspects of social life related to experiences of disability and chronic illness. Composition teachers can draw on these rich fields to teach the writing process and critical thinking/close reading skills because disability can be unpacked in a way that challenges what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2009) has famously called “the single story.” In conversation, teachers attempting this work often return to a central question, such as in my 2018 panel discussion attended by Jessica M. F. Hughes. How can composition instructors best inform first-year students’ progress as writers by teaching readings and academic concepts that can be theoretical or provocative—or both?

Disability as “a Good Difference,” Access as a Story: An Overview of El Deafo

Incorporating such content has its risks, since institutions depend on composition instructors to develop in their students crucial academic skills. Focusing elsewhere can distract from those objectives, to universal detriment and nobody’s benefit. Texts from disability literature are well suited for a first-year writing course because the issues they raise both demand effective representation and offer intriguing, unique intellectual and pedagogical opportunities. The opportunity in this essay is the possibility for teachers to use a multimodal, autobiographical text to present disability in a way that challenges the aforementioned “single story,” to view disability as social rather than medical, and as dynamic rather than fixed. A former student once described disability as “a good difference”—and deafness, of course, has its own complexities related to a given deaf individual’s relationship to ASL and American Deaf Culture. Also, I have worked with nonsigning deaf adults, who generally preferred the term “people with hearing loss.” The work of Bell taught alongside Sanborn, Luczak, and Ridloff brings to life that disconnection, one I witnessed from close range as a hearing person who would eventually sign far more fluently than the parent who first taught me the language.

If this presentation is done with intention and nuance, then access, like disability, can be framed less as a one-sided, regulatory reaction than as a fluid, interactive, narrative action. Such a shift can ripple far beyond the classroom, but can also impact areas in students’ own work as writers and, especially, as readers. Consider that word, access, as an affirmative act students have to undergo with texts and subjects—i.e., accessing an idea, finding a reading to be accessible.[2] It is a process for which many first-year composition students, in my experience, need an invitation to truly start mastering. That slant exploration of what access means makes disability, particularly as represented in Cece Bell’s autobiographical comic, worth examination in first-year writing classrooms. “It is precisely because El Deafo is a graphic novel, instead of a traditional text-only book, that it invited the students to explore and have conversations about marginalized and inaccessible (emphasis added) subjects,” writes Sara Kersten (2018, p. 283). “The emotional landscape of the form and the story is a form of visual and embodied witnessing, making visible the author first, and trauma second. It is Bell’s manipulation of the layers of narrative in conjunction with the graphic novel elements in this autobiography that causes readers to make connections among the verbal and visual, physical and emotional” (p. 283). While Kersten’s description of student reactions to this text covers the range I have witnessed, the demarcations she describes are rarely as neat. It gets messy, as may be any attempt to tackle disability and its language, rhetoric, discourse, and voice. The balance of this essay explores that messiness as articulated in student writing, suggests tactics for managing it, and discusses progress by a range of students, with a particular focus on a class of developmental writers. The off-color pun that gives this essay its title offers as good a place as any to start that exploration.

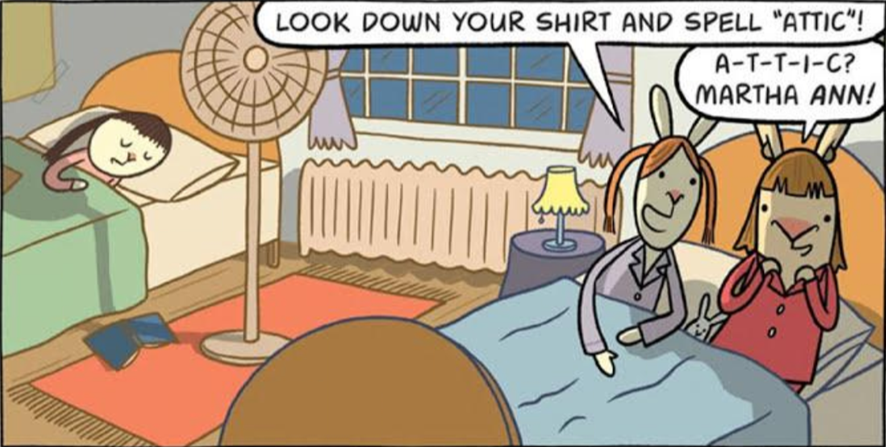

El Deafo (Bell, 2014) is an autobiographical graphic novel aimed at a middle-grade (ages 7-12) audience. The novel’s plot follows the character Cece Bell, starting when meningitis deafens her at age four. Cece briefly attends an oral school, an institution approaching deaf education with a strong focus on developing speech and hearing skills. Her family moves, and she enrolls at her local public school, a practice called mainstreaming. Cece has a series of unsatisfying friendships: insensitive Emma, bossy Laura, and condescending Ginny. The summer before fourth grade, she befriends a rising third grader named Martha. The girls have easy, natural fun together, as exemplified in the panel below (See Figure 1), which gives this essay its title; described below in detail, an act of access as much as a prelude to explication.

Figure 1. Young girls, Martha and Cece, chat at a sleepover, and joke about spelling “A-T-T-I-C” aloud. Cece Bell. (2014). El Deafo. Reprinted with permission of Abrams Books, New York, NY.

In the panel, two elementary-school-aged girls, Martha and Cece, talk at a sleepover. Both girls are drawn with rabbit ears. Cece has hearing aids. The girls share Martha’s bed. An older girl, Martha’s sister, sleeps in another bed in the same room. In speech bubbles, Martha tells Cece a joke: “Look down your shirt and spell ‘attic’!” Cece replies “A-T-T-I-C? MARTHA ANN!” Both girls laugh (See Appendix B for an Alt-text description).

At this first sleepover, Martha’s unconditional, nonchalant embrace leads Cece to elevate Martha—in her imagination—to sidekick of her alter ego, the eponymous El Deafo. The girls grow closer as Martha abets Cece’s crush on a neighbor and classmate named Mike. But then one day, while running around with Martha outside, Cece impales her eye on a tree branch. The injury requires an emergency room trip and an eyepatch—and, for readers, underscores the temporary nature of ablebodiedness. Martha blames herself, and Cece loses her sidekick and her confidence. At school, her classmates and teachers struggle to understand her deafness. This eases when Cece’s determination earns praise from her nemesis, the gym teacher, and when she shares with Mike and other classmates one of her “powers”: the way her assistive listening device allows her to “spy” (to borrow language that emerged in multiple class discussions) on their classroom teacher when she forgets to turn off Cece’s microphone. This allows Cece access to the teacher’s adult world, overhearing gossip with colleagues and trips to the bathroom. It also facilitates Cece’s ability to contribute to classroom hyjinx, as she listens—better than her peers could—for the teacher returning from an extended smoking break. Later, outside of school, Mike is testing the range of her assistive listening device when he crosses paths with Martha. She confesses her guilt to him, and Cece overhears it. Though Martha runs away in the moment, the two reconcile at the end, and Cece tells her prodigal sidekick everything about El Deafo.

Obviously, the novel’s main concern is friendship, particularly between girls on the edge of adolescence. Although Cece’s parents are largely out of frame, there are hints of the dynamics of friendship between adult women; Cece’s mother’s friendship with Ginny’s mother prolongs the girls’ friendship far longer than Cece would prefer, given Ginny’s condescending attitude (something students attached to immediately). In her book on the language of female friendship, linguist Deborah Tannen (Tannen, 2017), who is hard of hearing and uses hearing aids, cites the theory of psychologist Shelley Taylor about gender differences in responses to stress. “Fight or flight,” Tannen says, is typically male; Taylor’s research, she writes, describes the dynamic of female friends responding to stress as a tendency to “tend and befriend.” This dynamic reports the tendencies to care for others and affiliate deeply as a coping method (Tannen, xv). To extend this cautiously to El Deafo, Cece’s disability seems to cast her to others as the one who needs to be “tended” by those who she would rather just “befriend” (Tannen, xv). The disconnection between which of these reactions is appropriate creates a social barrier to affiliation that Cece’s deafness introduces. But that barrier is, ultimately, based in erroneous beliefs about deafness. In class discussions, first-year students often first cite her physical deafness as the reason for her social difficulties, but often recognize that the barrier is just as much in others’ attitudes as it is in Cece’s physical ears.

As a comic, El Deafo’s form strongly influences the interplay between friendship and disability. The visual presentation of the “A-T-T-I-C” page (See Figure 1) underscores Cece’s affiliation with Martha, while also making important points about language, rhetoric and discourse, and the way the comics genre presents and complicates the burgeoning “voice” of its deaf narrator. Students bring their language and assumptions to this text, and a writing class must address these assumptions at the level of diction and audience. Here, the structure of the joke helps students access a text-based analysis: What is the joke? Who is telling it? To whom? Why? Martha knows Cece is hard of hearing, but, in her language and her actions, she is assumption-free, and that extends to the stereotypical delicacy readers can assign to characters with disabilities. One of the warm, radical things about a dirty joke told to a deaf girl by her nondisabled friend is the complete refusal of the hearing friend to censor herself to an “innocent” disabled audience. This need to “tend” to the sensitivities of disabled characters, especially girls and women, is a projection that abounds in the canonical literature (i.e., Flannery O’Connor’s “Good Country People” (1971), to take just one example) that students may encounter in future courses.

The integrated visual and textual nature of graphic novels like El Deafo is also demonstrated by the joke. “A-T-T-I-C” by itself isn’t funny. With the inclusion of the visual of a girl looking down her shirt and the oral/aural input of spelling the word aloud, it is both funny and subversive—not just along the vectors of gender and age, but disability too, since deaf people are often excluded from oral/aural puns that require fruitless explanations and often end with a cold “Nevermind.” The joke barely works in plain text without the literal spelling out letter by letter, the drawn lines of these young girls at a sleepover being mischievous and adult in a way they don’t have the perspective to totally grasp. (As pre-pubescent girls, a “t-t” is not what they “c,” but they have the self-awareness to know that this embodied fact is in both of their futures, which heightens the shared humor and shares the joke with some of their readers.) It is, as Kersten (2018) suggests, a deeply intimate moment where the connection between the characters is real, and improvised, and private. Formally, the graphic novel genre slows students down to analyze at this depth, with the text pulling the reader forward in time and the art keeping the reader still in space. By learning to closely read even an individual panel, students can extend a narrative moment long enough to take its measure.

El Deafo and “the Material Dimensions of Composing” Expository Essays on Disability

As the above explication might suggest, despite the fact that this book is aimed at middle-grade readers, college-level instructors working through El Deafo’s themes with their class will need patience. One reason for this patience is that students—and instructors—will be drawing, since one of the best ways to understand the layers at work in El Deafo’s hybrid, multimodal, and age-specific world is to encounter “the material dimensions of composing” (Alexander, 2013; for lower- and higher-tech variations, respectively, see Shipka (2011) and Kallin (2018)). These experiences of illustration can influence traditional academic writing, as in an activity asking students to continue revising the words in a sentence until a peer can draw it. More than a glorified version of a writing game students might have played with a seventh-grade substitute teacher, this variation on the Surrealist exercise Exquisite Corpse asks students to invent, compose, and revise in dialogue with a live, meaningful audience across verbal and visual modes. “Comics complicate notions of authorship, make sophisticated demands on readers, and create a grammar and rhetoric as sophisticated as written prose, while also opening up new methods of communication often disregarded by conventional composition instruction.” (Sealey-Morris, 2015, p. 31). These demands and complications are opportunities for composition instructors, even when comics subvert students’ or even our own notions of textuality.[3]

While comics can disrupt old habits, students still must sit down with some kind of blank, into which they compose text with the words most readily available to them. In these earliest summaries and responses, their language often reflects unexamined societal assumptions. This was the case with the use of “unfortunately” in the initial responses to El Deafo: “[Cece] finds comfort in wearing a red bikini all the time and being close to her home. Unfortunately, she then realizes that she cannot hear anything either.” In the developmental writing class, where this passage was written, the initial writing that students composed in response to El Deafo prompted a lesson around the function of “unfortunately” as a transition word, and then on its connotation of pity, rather than the other way around. This framed the use of “unfortunately” as a writer’s decision to transition rather than a reader’s judgment of an inciting event—and, by inference, its consequent events—as negative. With that clarified, other transition options were discussed and applied in future drafts.

The above underscores how it takes a discourse community to write an essay—or, more to the point, each essay. With the essays written in response to El Deafo, that community-building starts on the day Bell’s text is introduced with a brainstorming session about d/Deafness. These brainstorms often reveal the two views of d/Deaf identity which even students with some prior exposure to Deaf culture or ASL must continually, dialectically confront.[4] For first-year writing students, brainstorms force an initial confrontation with what it means to be “cured” or “fixed.” These words are as loaded in disability studies as is the term “normal” (Garland-Thomson, 2016; Davis, 2007; Clare, 1999). Many works of contemporary d/Deaf and disability literature offer opportunities to explore this, with just one example being Jillian Weise’s essays (“Common Cyborg,” 2018), poems (“Cathedral by Raymond Carver,” 2014; and “Cafe Loop,” 2011), and satirical performance pieces as Tipsy Tullivan (Tullivan, 2019) in “Tips for Writers” web videos. As Kersten (2018) persuasively argues, Bell’s book is also one such text. “In stark contrast to other middle childhood books on disability experiences, El Deafo moves away from a medical view of disability, wherein disability is broadly depicted as a defect within the person that needs to be ‘cured or eliminated if the person is to achieve full capacity as a human being’” (p. 283). Kersten notes that, as a d/Deaf instructor herself, the text allows students a way to incorporate her lived experience while minimizing discomfort for her, and for them. As a disabled writer who selectively and judiciously incorporates my own experiences into discussions as a way to model positioning, I agree with Kersten that such exchanges help build trust that can be crucial for the community-building that informs discussions and prewriting activities. Interestingly, these brainstorming sessions are almost always organized visually (i.e., a web).

See What I’m Saying: Visual Presentations of Shared Discourse about Multimodal Texts

Effective visual presentation of shared discourse can help students make arguments toward a clearly defined audience that is broader than just their instructor. This was particularly clear in one class, part of an academic cluster at a public four-year college that read El Deafo alongside G. Willow Wilson’s Ms. Marvel: No Normal (2014) in a general education literature course called “Self and Other in Literature.” In their initial brainstorm, they identified a wider range of concepts than my developmental students. They listed adaptations to d/Deafness that included “ASL,” “cochlear implants,” “hearing aids,” oral education and speechreading; some students knew about mainstreaming; others suggested words related to the pathologizing of deafness: “cure,” “prevention,” and “treatment.” An important part of teaching any narrative of the d/Deaf experience is honoring its dual physical and cultural realities. Questions of language arose, like the terms “tone-deaf” and “fell on deaf ears,” as did the “right” and “wrong” words to use to refer to deaf people. (Yes to ‘d/Deaf,’ No to ‘hearing-impaired’ and ‘deaf-mute’; Ask to ‘hard of hearing’ and ‘person with hearing loss.’) Toward the end, a question arose about person-first and identity-first language, and we returned to that at the start of the next class with a short, in-class reading from John Lee Clark’s essay collection Where I Stand (2014).

This group adjusted to new ideas productively and quickly. In our first full day of discussion, they composed a collaborative list of topics that included toxic friendships; Cece’s frustrations with being misunderstood; the El Deafo persona and escapism; Cece’s treatment and others’ pity and condescension. This loosened the divide between planning and writing, allowing the accessible text to generate insightful, searching writing—the kind that is, to quote one student’s end-of-semester reflection, “unique and does not merely mirror the opinion of the writer whose work we are writing about.” This group often benefited from informal writing prompts similar to those used in community-based creative writing workshops facilitated in the mode of nonprofits such as Pat Schneider’s Amherst Writers & Artists and Aaron Zimmerman’s NY Writers Coalition. These workshops and activities with similar aims, conducted in more academic contexts, often center their practices on the connection between “the conscious strategy of writing to generate” (Jones, 2014, p. 64) and an increased “trusting in the act of writing to be a generative process” (2014).

To encourage this, early writing is often assessed informally, with checkmarks, oral comments, peer discussion, or as boardwork. For students accustomed to testing regimens—I think here of writers who refer to any reading, regardless of genre, as “the passage”—the divorce of writing generated in and for class from grades requires adjustment. For students whose creativity and voice is often trampled by standardized testing and students’ own low confidence in English, a restoration of the “trusting in the act of writing” (Jones, 2014, p. 64) can fuel considerable progress in a 15-week semester. For students who trust the process already, the rewards of greater freedom and challenging prompts that can extend their learning help to build on their existing abilities. In this latter group, El Deafo helped develop their analysis and explication. These students attended to the visual and literary modes with depth, and the content about disability only enriched most of their essays. The pre-writing and generative activities in this class offer a best-case outcome.

“Save Me!” from “Becoming Hearing”: Reviewing, Re-purposing, and Reframing

The same generative techniques of brainstorming and generative writing worked quite differently with the class of developmental students at the private four-year college. There, the brainstorm exposed a tendency to assume an answer, rather than to pose a question. This led to the production of statements that were flatly untrue: “most deaf people use sign language,” “if born deaf, can’t ‘talk,’” or “not genetic.” There were hints at the diversity of the deaf community, some of which came from other readings and lectures: “some deaf receive oral education” and “people who lose hearing later gradually lose their speech.” The rich brainstorm in the previous group had allowed a planning process that was generative and sustained, and to guide our discussion, our drafting, our question-posing, our text analysis, and our initial attempts at arguments over several weeks. By contrast, with these students, a combination of a lack of knowledge, a lack of questions, and a lack of reflection made that challenging. Two adjustments, reframing and reviewing previous (and somewhat re-purposed) writing prompts, helped build a foundation for their eventual essays.

The reframing happened right away, with a brief video by scholar H-Dirksen Bauman (TEDx, 2015), “On Becoming Hearing,” and an additional web, with the word “hearing” in the middle. Here “hearing” refers not to the action in its gerund form, but to the identity. Some of the crucial words it included were “multitasking,” “majority,” “associates language with speech,” “privilege of access,” and “most direct way to understand what others want to express”—the last of which was commented on (with as little consternation could be mustered) by the instructor as an example of audism (a word that was then added to the board). The later responses to El Deafo seemed to incorporate an awareness of audism as Bell’s main action moved away from the medical setting and into the school environment. It is hard to say whether the text shifted, or the writers shifted, or both, but a shift happened, as evidenced in this fairly typical sentence: “Cece should not feel small because of her hearing but rather large because while she may think that her hearing aids make her weird, they in fact perpetuate her as unique,” wrote one student. The openness here offered a starting point for an argument about how social “small” and “large” can be, rather than being a fixed condition with a fixed meaning.

This class had previously written about superheroes, particularly various takes on Superman, by examining works by Sherman Alexie (1998), Dorianne Laux (2011), John Hodgman (2013), and Chris Ware (2003). Toward the end of our work with El Deafo, we returned to a generative free-write called “Save Me!” in which students considered different rhetorical situations in which a person would deliver a message, namely: “Help!” These situations included alien abduction, animal attack, mutiny, or being marooned on an island. In concert with the comic and the Bauman video (TEDx, 2015), this revisitation led to a productive exercise, as we imagined these same calls with a response from the superhero El Deafo. One student described El Deafo planting her Phonic Ear’s microphone in the cabin of the rebels, saving the noble captain from a sea of sharks. This class also revisited the aforementioned sentence illustration activity. Bauman’s (2015) reframing of d/Deafness here as a “gain” was often illustrated in actions: several students, for instance, illustrated his personal example of an inability to sleep through noise. By reframing and reviewing in various reading and writing modes, students accessed the central notion of El Deafo—the idea of disability not as a pathology, but as a social experience influenced by the reactions and attitudes of many people. To the earlier point about content not overwhelming course objectives, the nature of the activities by which this progress was achieved also each addressed composition tasks like planning, arguing, analyzing, editing, and revising.

These in-class activities helped student language in final essays become more descriptive and neutral while sustaining a specific and effectively structured argument. A representative sentence follows: “At the beginning of this children’s comic, we can observe that time and time again, Cece uses her superhero facade in order to create a sanctuary of comfort when placed in uncomfortable positions.” The word choices here are careful and precise, and the claim is placed in the context of the work as a whole. This student, from the developmental class, has written a sentence that could dialogue with this one, from the more advanced class: “Superheroes are a representation of safety and come in times of distress. They were created for people who desperately wanted to be rescued, therefore, it’s not a surprise when El Deafo is that superhero for Cece.” In both cases, students focus on the function of the superhero for Cece. Importantly, both writers ascribe agency to her: Cece “want[s]” to be rescued, and the hero is of her own creation, her own response to her own “distress.” She is powerful; she saves herself. The writing plants images of this agency in the reader’s mind: she “uses” the El Deafo “facade” to “create” a “sanctuary of comfort”—a shield of sorts against the kind of erasure that has its roots in problematic public rhetoric and received wisdom about deaf and disabled characters.

“[W]hen They Fell in the Valley of Life”: Reflections and Conclusions

With my developmental students, I wondered if their initial reaction had been influenced by the book’s opening. Cece Bell’s El Deafo begins with the line, “I was a regular little kid.” This line often found itself reflected in summaries or responses: A common statement was, “Cece was a regular kid but (emphasis added) then she ended up getting meningitis.” To test this, I assigned a brief comparative reading, the first three chapters of Henry Kisor’s (2010) What’s That Pig Outdoors?, a more traditional personal narrative of post-lingual oral deafness. Of Kisor, one student wrote, “This reading material helped me to realize that deafness is not a pathology; instead it’s just a physical and social condition.” In independent summaries and responses, other students also showed growth in their ability, with support, to engage with ideas about the medical and social models of deafness. While some students continued to write without fully examining their assumptions (“The deaf people need to be treated equally to the normal people”), most reading and responses of this more traditional text recounted details, and a few connected them to El Deafo to a reference entry on Kisor’s book (Dalton, 2019). Some new ideas, emphasized more in Kisor (2010) than in Bell (2014), were explored, like overprotection and audiological diversity: “The best way to treat deaf children as normal kids is not to protect them that much.” Diversity within the d/Deaf community also emerged out of this reading, allowing us to circle back to the first day brainstorm and its errors. “Some journalists and commentators think that deaf people only use sign language; however, there are many deaf people [who] do not use sign language, they use spoken English and lipreading [sic],” wrote one student. Another wrote: “Deaf people have their own culture, they have different ways to communicate with others, some deaf people use sign language, some of them, like the author, depend on spoken language and lipreading.” This confidence showed with students attempting, often correctly, to incorporate new information and novel vocabulary. This included mention of the historic student protest at Gallaudet University that ended in the installation of the college’s first Deaf president, which was the occasion that led Kisor (2010) to write his memoir. Students also attempted to stake positions on ideas like total communication, language acquisition, and equality: “…deaf people should be treated equally so they can enjoy a full and productive life as hearing people do. To do so, they should have the same opportunity and resources to learn more complicated English like abstractions.” That last term, abstractions, was especially pleasing for me to see in their work, as it had been a concept many of these particular students had struggled to understand in our first weeks together. For many students entering this class, disability itself seemed an abstraction, one that had become more concrete.

Students developed paragraphs in response to Kisor (2010) that, despite some errors and some vestiges of problematic language, showed their evolution as nuanced writers and novice allies to deaf people: “Kisor himself, a good example, had a normal life with hearing children and began to love language,” includes both ‘normal’ and ‘hearing,’ and its focus is on Kisor’s progress. Paragraphs sustained these ideas at greater length and in greater detail. One student wrote:

For the author’s personal experience, it is unfortunate that his deafness is caused by an accident and that accident could have been avoided. But luckily, the author’s parents are ‘intelligent, cultured, and tough-minded.’ Being educated is very important, it is not only learning skills for work, but it is also a broadening of the horizon, it helps people when they fell in the valley of life.

Despite one “unfortunate” word choice—deployed appropriately here, with its focus on prevention—the writer carefully considers the social perspectives of various stakeholders: Kisor, his parents, people who “fell in the valley of life.” The one thing missing here is a clearly positioned “I” connected to the analysis in a sophisticated, authentically reflective way. That is evident in this student’s work, which incorporates some extended reflection:

I never really had any kind of encounter with a deaf person before, but if in the future I do I’ll know how to approach them. Their discomfort walking in a hearing world is something I never really took into account along with the many people that they encounter [who] show them pity, when in reality they don’t feel as they should be pitied. Viewing the world from the perspective of Henry Kisor made me aware of my privilege…The idea of being deaf is something that hearing people fear, but when it is really your life it’s something you adapt to. I learnt [sic] that being deaf isn’t something anyone should fear, but learn from.

Too often, the definition of effective reflection is withheld by teachers, some of whom (myself included) are guilty of a “I know it when I see it” approach to assessment. Perhaps this is because reflection is so personal: “Even in the best of circumstances, revealing what we value in such a text makes us vulnerable in ways that discomfit” (Yancey, 1998. p. 82). Making our assumptions known can model that behavior for our students. Composition instructors, whose students are only beginning the process of interrogating assumptions and beliefs that will continue throughout college, have to approach close reading, discussion, and writing so that students can challenge received wisdom in ways that develop their critical thinking and analytical writing skills. One reason students struggle with writing is because they fail to see reading as it must be seen in college: as a dialogic, discursive, and communal activity (Hawes, 2018). El Deafo is an unusual enough text in its form and content that it forces many students to engage anew in reading, thinking, and writing.

Disability as a topic, too, can force teachers to position themselves and their ways of thinking, especially if a teacher introduces activist reframings, such as the notion of able-bodiedness as temporary and the notion of disability as both undeniably located in the body and an equally social experience of embodied difference. Students often recount an example I frequently use: of the wheelchair user who is not denied access from a building until the architect decides that stairs are the one way in. What I hope they learn is that stories give access—and inaccessibility—a human face. In El Deafo, that face also has a rabbit’s ears.

I mentioned earlier having accommodations in high school and graduate school, but not college. Essentially, authorities (my surgeons) told me I had recovered and that the description of my brain by specialists (educational psychologists) was temporary. This is erasure; it’s a culturally powerful and personally seductive narrative of fixing, told by the fixers rather than the ‘fixed.’ Suffice it to say that this is untrue, and that the same areas of “highly discrepant” cognition found in 1995 are just as “highly discrepant” in 2019. I often mention this on the first day of classes, when I read the college syllabus statement on access, and my own evolving version of what access means in my classrooms. My own story helps narrate the otherwise abstract idea that learning varies widely, and that assumptions about the body underpin countless daily social decisions by temporarily able-bodied people. Most importantly, sharing my story helps start the discussion about whether or not these assumptions are benign. To my mind, quite often, they are not. Rather, they are greased pistons in the quiet engine of ableism, the system of beliefs and defaults that “normalize” certain bodies and define others as deviant. To return to the writing classroom, it is an engine composed of language, including the decisions made by all writers—including our students—at the level of a sentence, a phrase, or a single word.

Footnotes

[1] On using capital-D: When referring specifically to American Deaf Culture, the term “Deaf” is used (i.e., “my father does not attend any Deaf social events”). The lower-case “deaf” refers to the generic physical condition (“my father has been profoundly deaf since his 30s”) and also to the social experience/identity of nonsigning deaf people. The use of “d/Deaf” indicates a statement that includes both groups.

[2] The graphic novel form is by definition inaccessible to students with visual impairments. While some entities produce original audio content adapted from comics (i.e., Graphic Audio) and others create audio accessible versions of print and visual content (i.e., Comics Empower), I have not found an adaptation of Bell’s work, and instructors seeking to accommodate a student with a visual impairment might have to substitute another text. (In the same course, students read Wilson’s Ms. Marvel: No Normal (Wilson, 2014), which has connections with El Deafo. Ms. Marvel does have a Graphic Audio edition (Wilson, 2015), and it is excellent listening.)

[3] Nick Sousanis’s website, Spin Weave and Cut, describes his work of narratology in comics form [Unflattening], which began as a Columbia University dissertation. The “Unflattening in the Classroom” website subsection details a French university graduate student’s request for a library copy of Unflattening. The librarian responded, “Due to the difficulty of classifying this document within our current organizational system, it has been placed in storage.” (Translation: Jenny Meyer).

[4] As I can attest, from working as an ASL-English interpreter and interpreter trainer, even professional interpreters must examine their assumptions about disability. A professor once told a classmate of mine, bluntly, “Not all Deaf people are your parents.” That classmate is now a nationally certified interpreter and one of the best. She is also our former professor’s colleague at an interpreter training program.

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Alexander, K. P. (2013). “Material affordances: The potential of scrapbooks in the composition classroom.” Composition Forum, 27 (Spring). Retrieved from https://compositionforum.com/issue/27/material-affordances.php

Alexie, S. (1998, April 19) “The joy of reading: Superman and me.” Los Angeles Times, pp. 15–18.

Bell, C. (2014). El Deafo. New York, NY: Abrams Books.

Bowden, D. (1995). The rise of a metaphor: “Voice” in composition pedagogy. Rhetoric Review, 14(1), 173-188. doi.org/10.1080/07350199509389058

Browning, E. R. (2014). Disability studies in the composition classroom. Composition Studies, 42(2), Fall, 96-117.

Brueggemann, B. J., White, L. F., Dunn, P. A., Heifferon, B. A., & Cheu, J. (2001). Becoming visible: Lessons in disability. College Composition and Communication, 52(3), 368-398.

Clare, E. (1999). Exile and pride. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Clark, J. L. (2014). Where I stand: On the signing community and my deafblind experience. Minneapolis, MN: Handtype Press.

Commerson, R. (2012, May 25). Temporary Frame: SSI=Activist Salary. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CU7tmkFGEY0

Dalton, T. K. (2019). Henry Kisor’s What’s that pig outdoors: A memoir of deafness (1990): Disability experiences reference guide. In Press. Columbia, SC: Layman Poupard Publishing.

Davis, L. (2007). Deafness and the riddle of identity. The Chronicle of Higher Education [The Chronicle Review], 53(19). Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/Deafnessthe-Riddle-of/23778

Dunn, P. (2010) Re-seeing (dis)ability: Ten suggestions. The English Journal, 100(2), 14-26. doi:10.2307/25790025

Freire, P., & Shor, I. (1987). A pedagogy for liberation: Dialogues on transforming education. London: MacMillan.

Garland-Thomson, R. (2016, August 19) Becoming disabled. [Opinion, Section SR, P. 1] The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/21/opinion/sunday/becoming-disabled.html

Gould, K. (2008). What we talked about when we talked about disability. Teaching English in the Two Year College, 36(1), 27-37.

Hawes, S. (2018, February 12). Reading reframed for the community college classroom. Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching Strategies from Magna Publications. Retrieved from https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/reading-reframed-community-college-classroom/

Hodgman, J. ( 2013, October 18). Flight vs. invisibility: Invisible Man vs Hawkman. In This American life, episode 508: Superpowers. [Audio podcast] [Transcript]. Retrieved from https://www.thisamericanlife.org/508/superpowers-2013

Hsu, V. J. (2018). Reflection as relationality: Rhetorical alliances and teaching alternative rhetorics. College Composition and Communication, 70(2), 142-168.

Jones, S. (2014). From ideas in the head to words on the page: Young adolescents’ reflections on their own writing processes. Language and Education, 28(1), 52–67. doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2013.763820

Kallin, J. (2018). Visualizing ambient rhetorics. Present Tense Journal, 7(2). Retrieved from https://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-7/visualizing-ambient-rhetorics/

Kennedy, T. M., & Menten, T. (2010). Reading, writing, and thinking about disability issues: Five activities for the classroom. The English Journal, 100(2), 61-67.

Kersten, S. (2018). “We are just as confused and lost as she is”: The primacy of the graphic novel form in exploring conversations around deafness. Children’s Literature in Education, 49, 282–301. doi.org/10.1007/s10583-017-9323-9

Kisor, H. (2010). What’s that pig outdoors: A memoir of deafness, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Laux, D. (2011). Superman. In Laux, The book of men: Poems. (pp. 33-34). New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

O’Connor, F. (1971). Good country people. In O’Connor, The complete stories (pp. 271-290). New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Arsenal Pulp Press.

Price, M. (2011). Mad at school: Rhetorics of mental disability and academic life. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Schneider, P. (2003). Writing alone and with others. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sealey-Morris, G. (2015). The rhetoric of the paneled page: Comics and composition pedagogy. Composition Studies, 43(1), 31-50.

Shipka, J. (2011). Toward a composition made whole. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Stewart, M. (2010). Doubly vulnerable: The paradox of disability and teaching. The English Journal, 100(2), 61-67.

Tannen, D. You’re the Only One I Can Tell: Inside the Language of Women’s Friendships. Ballantine Books, 2017

TEDx. [Bauman, H-D.]. (2015, March 6). On becoming hearing: Lessons in limitations, loss, and respect. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yCuNYGk3oj8

Tullivan, T. [Weise, J.]. (2019, January 7). Tips for writers [Video file]. Retrieved from United States Census Bureau. (August 3, 2018). Anniversary of Americans with Disabilities Act: July 26, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2018/disabilities.html

United States Census Bureau. (August 3, 2018). Anniversary of Americans with Disabilities Act: July 26, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2018/disabilities.html

Ware, C. (2003). Jimmy Corrigan: The smartest kid on Earth. New York, NY: Pantheon.

Watkins, R. D. & Lindsley, T. (2015). Sequential rhetoric: Using Freire and Quintilian to teach students to read and create comics. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 9(4).

Weise, Jillian. (2011). Cafe loop, Wordgathering, 5(2). Retrieved from http://www.wordgathering.com/past_issues/issue18/poetry/weise.html

Weise, Jillian. (2014). Cathedral by Raymond Carver, The Literary Review, 57(4), 122.

Weise, Jillian. (2018). Common cyborg. Granta (online edition, 24 September). Retrieved from https://granta.com/common-cyborg/#r2

Wilson, G. Willow. (2014). Ms. Marvel Vol. 1: No normal. New York, NY: Marvel Worldwide.

Wilson, G. Willow. (2015) Ms. Marvel Vol. 1: No normal. [CD]. Graphic Audio [Out of Print] . Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Ms-Marvel-1-No-Normal/dp/1628511915/ref=tmm_abk_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Yancey, K. B. (1998). Reflection in the writing classroom. Louisville, CO: Utah State University Press

Appendix

Alt-text as a Teaching Tool

Alt-text is its own kind of rhetorical situation, with its own conventions—brevity among them. This six-sentence description (below, exeample A.) for Figure 1 began as an alt-text box, and its curt syntax and concrete diction stand out even as I finished this essay. I retain them in the body of this essay because the contrast demonstrates yet another opportunity access presents in composition courses: the opportunity to use access features like alt-text as a teaching tool. Formally composing image descriptions can be a great way to invite writers into interpreting visual text in a way that creates access. Whether or not students in the room require alt-text, everyone benefits from having it.

- Figure 1, alt-text description.

In the panel, two elementary school aged girls, Martha and Cece, talk at a sleepover. Both girls are drawn with rabbit ears. Cece has hearing aids. The girls share Martha’s bed. An older girl, Martha’s sister, sleeps in another bed in the same room. In speech bubbles, Martha tells Cece a joke: “Look down your shirt and spell ‘attic’!” Cece replies “A-T-T-I-C? Martha ANN!” Both girls laugh.

- Figure 1, using an illustration caption for print media.

Figure 1. Young girls, Martha and Cece, chat at a sleepover, and joke about spelling “A-T-T-I-C” aloud in the context of deafness. Cece Bell. (2014). El Deafo. Reprinted with permission of Abrams Books, New York, NY